eISSN: 2379-6367

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 4

Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Kedah D.A, Malaysia

Correspondence: Naeem Hasan Khan, Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Kedah D.A., Malaysia, Tel +60 169372470

Received: August 12, 2025 | Published: August 28, 2025

Citation: Hua WWS, Perveen N, Khan NH. Screening of phytochemicals, antioxidant activity determination and identification of Quercetin and Catechin using fourier transformed infrared spectroscopic method (FTIR) for Actinidia chinensis (Chinese gooseberry) (Kiwi fruit). Pharm Pharmacol Int J. 2025;13(4):142-153. DOI: 10.15406/ppij.2025.13.00478

Introduction: Oxidative stress is a major contributing factor to the onset and progression of chronic illnesses, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders, as a result from an imbalance between reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in the body. In response, there is growing interest in natural antioxidants from fruits and plants as safer, health-supportive alternatives to synthetic compounds. Actinidia chinensis (commonly known as Chinese gooseberry or kiwi fruit) is widely valued for its high vitamin C content and nutritional value. However, there remains a lack of detailed research into specific phytochemicals responsible for their antioxidant activity, particularly compounds such as quercetin and catechin. This research focuses on analyzing the phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential of A. chinensis, with a particular focus on detecting and understanding key flavonoids like quercetin and catechin.

Objectives: The primary objective of this study was to determine the phytochemical constituents, evaluate the antioxidant potential, and characterize the presence of quercetin and catechin in Actinidia chinensis using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

Method: Fresh A. chinensis was subjected to maceration extraction using 95% ethanol. The resulting extract was evaluated using three primary approaches, which includes phytochemical screening to detect the presence of bioactive classes of compounds, antioxidant activity evaluation using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for chemical characterization of quercetin and catechin.

Result: The phytochemical screening revealed the presence of flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, alkaloids, and carbohydrates. In the DPPH assay, the extract showed a strong dose-dependent increase in radical scavenging activity, ranging from 28.67% at 50µg/mL to 90.93% at 1000µg/mL. The ethanolic extract had an IC₅₀ value of 178.33 µg/mL, while the reference standard BHT showed a lower IC₅₀ of 133.08µg/mL. This demonstrated that A. chinensis extract is less potent than the standard antioxidant under the same conditions. Furthermore, key absorption peaks observed in FTIR analysis correspond to functional groups found in the known FTIR spectra of quercetin and catechin, strongly suggesting the presence of these flavonoids in the extract. These results indicate that A. chinensis possesses a diverse phytochemical profile, predominantly rich in antioxidant-related compounds.

Conclusion: To conclude, this study successfully demonstrated that Actinidia chinensis is a promising natural source of antioxidant rich phytochemicals and possesses strong antioxidant properties. The findings from phytochemical screening, DPPH antioxidant testing, and FTIR spectral evidence collectively indicate that compounds such as quercetin and catechin are likely present in the extract. These findings fulfill the research objectives that not only support future research in investigating traditional health benefits associated with A. chinensis but also act as a cornerstone for further exploration into its therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Actinidia chinensis, phytochemicals, flavonoids, antioxidant activity, FTIR spectroscopy

Chinese gooseberry (Actinidia chinensis)

The global interest in functional foods and natural health-promoting compounds has significantly increased in recent years, with a particular focus on fruits abundant in bioactive phytochemicals. Chinese gooseberry represents a prime example of a nutritionally complex fruit with high potential to enhance human health and well-being. Despite its widespread consumption, a comprehensive understanding of its phytochemical composition and associated health benefits remains an area of active scientific investigation. The Chinese Gooseberry, now more commonly recognized all over the world as the golden kiwi fruit, is a small nutritious berry that has been cultivated for centuries and has major potential in both agricultural and pharmaceutical domains. It was native to the mountainous regions of China but was introduced to New Zealand in 1904,1 where it thrived and became one of the most distinctive subtropical fruits that dominates the market. At present, kiwifruit production has grown significantly worldwide with major producing countries including China, New Zealand, Italy, Greece and Chile. It has a high impact on economic importance, having a global annual production surpassing 4 million tonnes and a steadily increasing market value due to its unique appearance, rich nutritional benefits and versatile uses.2 This surge in production is driven by consumer demand for healthy and flavourful fruits, coupled with the recognition of the Chinese gooseberry's unique nutritional profile, which evolved it from a relatively unknown local fruit to a widely traded international berry. Even though traditionally it was renowned for its high vitamin C content and dietary fibre,3 recent research strongly emphasized the antioxidant potential of Chinese Gooseberry due to its rich phytochemical composition, which includes a diverse range of flavonoids, carotenoids and polyphenols.4

These compounds have demonstrated promising benefits in addressing oxidative stress, aiding digestive health, supporting immune function, and potentially alleviating various chronic health conditions such as blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, constipation or asthma.5 As such, the growing recognition of kiwifruit's diverse health benefits has made it a subject of increasing interest in both scientific research and the food industry.

Research rationale

Chinese gooseberry was selected for this study due to its rich phytochemical composition and rising popularity as a health-promoting fruit. The focus on quercetin and catechin stems from their strong antioxidant potential and documented health benefits. Furthermore, investigating the antioxidant activity of kiwifruit aligns with the growing demand for natural antioxidants in combating oxidative stress-related diseases. Additionally, while extensive studies exist on the antioxidant properties of various fruits, kiwifruit remains underexplored in terms of its flavonoid content and antioxidant potential, particularly quercetin and catechin. Lastly, prior studies have not extensively utilized Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in phytochemical research of kiwifruit, which highlights a significant lack of study in this aspect.

Morphology and botanical classification of Chinese gooseberry

The scientific botanical name of Chinese Gooseberry is Actinidia chinensis, from the family of Actinidiaceae. The plant is characterized by its large, deciduous, and dioecious branching stems that coils itself around nearby plants for structural support and can extend up to 30 meters in length. This kiwi fruit species gave rise to the cultivated variety of modern kiwi fruit we consume today, known as Actinidia deliciosa.6 It thrives in dense shrubs and oak woods on slopes or in ravines.7 The heart-shaped leaves are the striking features of the plant, where it can turn reddish in autumn and may grow up to 25cm in width. Both the leaves and fruit can be eaten. The golden-yellow, rounded fruit with smooth, golden-brown skin is rich in nutrients and contains small, edible seeds. The leaves are suitable for consumption once cooked when it is necessary. It produces sweet-smelling, creamy-white to yellowish flowers in the spring. The leaves, flowers and fruit for Chinese gooseberry is illustrated in Figure 1. The botanical classification of Chinese gooseberry is explained further in Table 1.

|

Kingdom |

Plantae |

|

Phylum |

Streptophyta |

|

Class |

Equisetopsida |

|

Subclass |

Magnoliidae |

|

Order |

Ericales |

|

Family |

Actinidiaceae |

|

Genus |

Actinidia |

|

Species |

Actinidia chinensis |

|

Variety |

Actinidia chinensis var. chinensis |

Table 1 Taxonomical classification information of Actinidia chinensis

Phytochemical screening is a qualitative scientific procedure that is widely used as an assessment tool in identifying the presence of different phytoconstituents with therapeutic potential in any part of the plant.8 It is a complex process that often begins with careful preparation of a plant material, which includes washing, drying, and grinding.9 It will be then subjected to extraction techniques using a suitable solvent, where the active compounds can be obtained for further analysis of their chemical composition for research purposes. This analytical approach helps to expose the major constituents in the plant materials and detect useful biochemical compounds that may contribute to wellness and health of a being.10 Therefore, evaluating the findings of phytochemical screening in fruits, particularly kiwifruit, may provide an in-depth understanding of their nutritional profile and potential therapeutic properties to enhance the quality of life.

Major phytochemical groups identified in kiwi fruit

Kiwi fruit typically holds a variety of bioactive phytochemicals including phenolic acids, flavonoids, triterpenoids, lutein, carotenoids, isoflavonoids, and several other secondary metabolites.11 He et al.,7 revealed that phenolic acid constituents and triterpenes are the major chemical components present in the fruit. Among these, 42 types of triterpenes found in the roots exhibit potential anti-tumor properties, while phenolic compounds responsible for antioxidant effects are detected in all parts of the fruit. These compounds contribute to the fruit's capacity to combat oxidative stress. According to Mai et al.,12 the key phenolic compounds present in kiwi fruits comprise of phenolic acids like chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid and caffeic acid; flavonols like quercetin 3-O-glucoside and quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside; and flavanols like procyanidin B2, procyanidin B1, epicatechin and catechin. However, the abundance of phenolics present varies across studies. In the previous study, neochlorogenic acid, procyanidin B2, and epicatechin were identified as the most concentrated phenolic compounds in the fruit, whereas HY Li et al.,13 noted that procyanidin B1 and chlorogenic acid were predominant as well. Another study by El Azab et al.,14 found that carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, phenolic, flavonoids, folic acid, saponins, and tannins compounds after extraction with solvents of different polarity. Montefiori et al.,15 also detected chlorophylls, anthocyanins, and carotenoids in the flesh that contributed to the fruit’s color. Further analysis by K Li et al.,16 demonstrated that both aqueous and alcoholic extracts yielded two types of phytochemicals. The study revealed two phenolic compounds, specifically quercetin and catechin, alongside a range of flavonoids including p-coumaric acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid and tannic acid. Overall, kiwi fruit is a valuable source of phytochemical compounds with antioxidant and health benefits, but the differences in phytochemical levels across studies show the need for more research to better understand its full composition.

General structure and classification of flavonoids

Flavonoids are grouped into six classes, including flavanone, flavonol, flavone, isoflavone, flavan-3-ols, and anthocyanin.17 The core chemical structure of flavonoids comprised of two benzene rings (ring A and B) linked to a pyran ring (ring C) by a three-carbon bridge.18 The antioxidant activity of flavonoids depends on the location of the B ring on the C ring and the number and placement of hydroxy groups on the B ring. These hydroxy groups help to stabilize free radicals by donating electrons and provide antioxidant protection to the cells.19 General chemical structures and classification of flavonoids is shown in Figure 2.

Significance of quercetin and catechin

Among the many phytochemicals present in kiwifruit, quercetin and catechin stand out for their particularly strong antioxidant capabilities. Quercetin is widely known for its anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer effects,20 while catechin is recognized for its ability to improve cardiovascular health and regulate blood sugar levels as well.21 Both compounds help to combat free radical-induced cell damage, playing a key role in preventing diseases like cancer, heart problems, and neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore, the presence of these compounds in kiwifruit warrants further investigation, as understanding their concentrations could provide significant discoveries into the fruit's potential therapeutic applications.

Quercetin: properties and health benefits

Quercetin molecules contain a basic flavonoid core that has one hydroxyl group located on position 3 of ring C, two hydroxyl groups on positions 3 and 4 of ring B, and two more hydroxyl groups on positions 5 and 7 of ring A.22 Additionally, a carbonyl group substituent is attached to carbon 4 of ring C. In Figure 3, the chemical structure of quercetin is illustrated.

Quercetin is part of the flavonol subgroup of flavonoid compounds and is categorized as one of the polyphenol constituents abundantly present in kiwi fruit.23 Yang et al.,24 believes that quercetin possess strong antioxidant activity due to the attachment of phenolic hydroxyl group and double bonds in its chemical structure. The mechanism of action of quercetin in inducing antioxidant effect is presumed to involve scavenging free radicals to protect the cells from damage, chelation of metal ions like Cu²⁺ and Fe²⁺ through its catechol structure and protecting low-density lipoprotein (LDL) from oxidative damage.25 Among the flavonoid group of phytochemicals, studies by Hadidi et al.,26 and Yang et al.,24 identified quercetin as one of the most effective flavonoids in neutralizing free radicals with the highest antioxidant potential through DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. In addition to its antioxidant properties, quercetin exhibits strong antibacterial activity27 and can reduce inflammation by controlling the release of inflammatory factors.28 It is demonstrated in a study by Kang et al.,29 in vitro, where quercetin produces anti-inflammatory effects by reducing nitric oxide production in macrophage cells. Quercetin is also known to support cardiovascular health by preventing platelet clumping, relaxing arteries, and improving blood pressure.30 It also exhibits strong anti-cancer properties by promoting tumor cell death (apoptosis) and slowing the growth and spread of tumors in tissues like the brain, colon, and liver.31 Furthermore, one study by Dhanya,32 had highlighted the potential of quercetin in improving the symptoms of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This notion is supported by Bule et al.,33 by proving that it can reduce the blood glucose level at significant doses and manage hyperglycaemic condition. It also has antiviral properties, as it may prevent viruses from entering cells during the first step in the virus replication process by interacting with the influenza NA protein.34

Catechin: properties and health benefits

The catechin molecule contains a basic flavonoid base structure similar to quercetin. However, unlike quercetin, catechin lacks a carbonyl group and a double bond located between positions 2 and 3 of ring C. In Figure 4, the chemical structure of catechin is illustrated.

It belongs to the flavan-3-ol subgroup of flavonoid compounds. It is also categorized as one of the polyphenol constituents that can be found in many fruits. Even though it is generally found in green tea, cocoa, or wine,35 one study from Arts et al.,36 showed that kiwi fruits contain approximately 4.5 mg/kg of catechin, present in both its peel and flesh (Alim et al.). Azab & Mostafa14 and Alim et al., identified catechin, epigallocatechin and epicatechins as the most predominant types of catechin constituents in kiwifruit. Catechins are potent antioxidants capable of interacting with mitochondria to produce metabolic effects.37 These actions are primarily attributed to the existence of phenolic groups in the molecular structure, in which it can disrupt and block the actions of intracellular ROS to directly stabilize the free radicals in our body. According to Fan et al.,38 catechin has demonstrated the strongest ability to scavenge free radicals. However, some studies,39,40,41 suggest that quercetin may exhibit superior antioxidant activity compared to catechin derivatives. Beyond their antioxidant properties, catechins have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects by modulating inflammatory pathway.42 This is achieved through inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, lowering the expression of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase, and stabilizing mast cells. All of which are linked to preventing anti-inflammatory related chronic diseases such as arthritis, atherosclerosis and ocular disorders,43 though further studies are needed for specific actions of catechin on vascular function.44 Catechins also appear to block specific enzymes and signalling pathways involved in the development and spread of carcinogenic cells and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disorders.45 A comprehensive study by Mangels & Mohler,46 also supports the fact that catechin intake in our diet provides significant cardioprotective effects. Additionally, they may act on the central nervous system by reducing the risks of neurodegenerative conditions47 and help manage hyperglycaemia by improving insulin resistance.21

Antioxidant activity

Free radical scavenging capacity of Chinese gooseberry with different antioxidant assessments

One of the primary therapeutic benefits of Chinese gooseberry (Actinidia chinensis) lies in its strong ability to neutralize free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative stress. Studies have demonstrated that the combination of vitamin C with phytoconstituents like polyphenols, alkaloids and terpenoids works synergistically to produce high levels of antioxidant activity.16 Various antioxidant activity assays are extensively utilized for the determination of free radical-scavenging capacity of fruit extracts based on their versatility and sample compatibility. These approaches deliver an in-depth evaluation of a fruit’s antioxidant capacity. For instance, Alim et al. tested the antioxidant capacity of Actinidia chinensis peel and flesh using DPPH and ABTS+ assays. It showed that both parts possess significant antioxidant properties. Nevertheless, the peel consistently demonstrated stronger scavenging activity compared to the flesh, with inhibition rates reaching 84.5% at 40μg/mL and 90.0% at 60μg/mL in DPPH and ABTS+ assays, respectively, while kiwi flesh showed a gradual increase in activity with concentration. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Liu et al., in having values of 13.25 mg AAE/g to 18.31 mg AAE/g using ABTS assay, confirming that antioxidant capacity of a kiwi peel is higher compared to the pulp. The results suggested that consuming the whole fruit, including the peel, can maximize its health benefits.

Zhang et al.,48 further developed the antioxidant evaluation by employing the peroxyl radical scavenging capacity (PSC) and cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) assays. The PSC assay method offers more advantages over traditional methods like DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays as it utilizes peroxyl radicals that are more natural occurring in the body. Additionally, Saeed et al.,49 reported that red kiwi fruit showed the strongest antioxidant activity at 237.544 ± 4.12μM QE equivalent/g FW with an EC50 of 0.0128 mg/ml. A lower EC50 value indicates higher potency, meaning that this fruit is very effective at neutralizing oxidative stress at a small concentration. But among all varieties of kiwifruit, it is determined in both the DPPH and ABTS assays that Actinidia chinensis variety had the strongest capacity for scavenging free radicals.50 Most of the studies prefer using DPPH assays to determine antioxidant activity because it is stable and quick in analyzing the sample.51 Overall, the use of diverse antioxidant assays highlights the strong antioxidant properties of kiwifruit and signifies as a natural resource for reducing oxidative stress.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis of Chinese Gooseberry

In the field of phytochemical research, there has been an increase in the application of advanced analytical instruments to study the chemical constituent of natural substances.52 One such technique is Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, which is a powerful analytical method in assessing the molecular profile of phytochemicals.53 FTIR operates by detecting the absorption patterns of infrared light in the sample.54 This is done by shining infrared radiation on a sample and observing how the material absorbs energy at different wavelengths. The absorption helps determine the functional groups and molecular structures of compounds, by providing a unique spectral fingerprint of the chemical bonds present. It can identify unknown materials in solid, liquid, or gas form by analyzing from a wavelength range of 4000 - 400 cm−1.55 This method is non-destructive, rapid, affordable, and efficient.56 Its application in phytochemical analysis allows for the precise identification of bioactive compounds, enhancing our understanding of their role in health promotion.

Applications of FTIR spectroscopy in phytochemical analysis

Recent studies have increasingly employed Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to analyse plant phytochemicals. Johnson et al.,57 claimed that it is proven reliable for estimating total phenolic content in a wide variety of powdered plant samples from different plant parts and can effectively detect total antioxidant content. For example, Kainat et al.,58 used FTIR spectroscopy to show that the peels of Solanum lycopersicum contain higher phenolic content than the pulp by interpreting the spectra peaks from FTIR spectroscopy. The same goes for Kale et al.,59 who had compared and identified types of functional groups in different leaf extracts of Thalictrum dalzelli Hook, while Pharmawati & Wrasiati,60 had classified functional groups present in the powder and leaf extract of Enhalus acoroides using FTIR spectroscopy analysis. These studies indicated that it is quick to produce results, easy to use, and low in cost.

Comparative studies of phytochemical analysis methods for kiwi fruit

The analysis of phytochemicals available in kiwifruit has traditionally relied on conventional techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and thin layer chromatography (TLC). HPLC analysis is utilized to analyze phenolic compounds and flavonoids in natural foods61 because it can precisely and rapidly produce both qualitative and quantitative results.62 This is demonstrated in studies by Azab & Mostafa14 and Deng et al.,63 in using HPLC analysis to identify the composition of phenolic compounds in extracts of kiwi fruits. Likewise, TLC has provided a cost-effective, preliminary method for identifying phenolic compounds and flavonoids by allowing simultaneous separation of multiple samples under identical conditions and separating complex plant extracts with similar compounds.64 For instance,65 utilised thin layer chromatography to differentiate phytochemical compounds in fruit extracts of Actinidia Deliciosa. Despite their accuracy, these methods have limitations. Chemical compounds that show overlapping peaks make the separation process complicated for HPLC analysis, and it can be costly to gather organic materials.66 TLC process can be simple; however, it is less sensitive, has inadequate resolution and requires complex sample preparation process.67 On the other hand, FTIR spectroscopy offers significant advantages over traditional methods for phytochemical analysis.

The primary advantage of FTIR lies in its ability to rapidly and precisely analyze samples with minimal preparation, do not require large sample volume,68 reducing time and cost,69 compared to traditional analytical methods. This eliminates the need for chemical reagents and minimizes waste production as well. Additionally, FTIR can handle a wide range of plant-derived materials, including fresh, dried, or powdered samples, making it a versatile option for phytochemical analysis.70 Therefore, some studies had begun employing FTIR analysis to identify the presence of bioactive components in kiwifruit, including Leontowicz et al.,71 who evaluated the bioactivity of various cultivars and families by comparing the IR absorption bands in various kiwifruit samples. Park et al.,72 assessed the phenolic content with FTIR spectrum to compare the antioxidant activity of different fruits with standard kiwi fruits. Besides that, a study by Santos et al.,73 also used FTIR to determine the level of kiwi fruit quality and the results showed a strong correlation between antioxidant capacity results from conventional methods and FTIR analysis. Hence, FTIR spectroscopy can be regarded as a promising alternative instrument in analyzing phytochemicals in kiwi fruit, which is helpful in advancing phytochemical research in other fruits or plant materials.

Collection and preparation of plant material

12 fresh kiwi fruit that weighed 2.0 kg each were purchased on 16th April 2025 from fresh vegetable market in Penang, Malaysia. The plant material was washed with clean distilled water and then 95% ethanol to remove dirt and contaminants. The fruits were then cut longitudinally into half using a clean knife. The peel and seeds inside the fruit were removed carefully using a spatula and discarded. The flesh was taken and mashed into smaller pieces to increase the surface area in exposing to extracting solvent as shown in Figure 5. Actinidia chinensis was separated from flesh, peel and seeds.

Maceration process and phytochemical screening

Chemicals

Maceration extraction method with ethanol

Approximately 300g of small pieces of raw materials were weighed on an analytical weighing balance. A 1000 ml conical flask was prepared and cleaned with distilled water and ethanol. All the raw materials were transferred into the conical flask, and then ethanol was added into the flask up to 1000 ml until all the raw materials were fully immersed and covered. The mixture was stirred thoroughly to ensure even distribution of the content. The flask was sealed with 3 small sheets of aluminum foil wrapped around the mouth to cover the opening. It was then left to macerate at room temperature by shaking gently daily using an orbital shaker at 140 rotations per minute (rpm) for 5 days. After the extraction period, the extract was homogenized into a homogenous paste using a blender, filtered using two clean muslin cloths, and then collected in a 1000 ml conical flask. After that, the extract was evaporated by using a Rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at a temperature of 45 °C for 120 rotations per minute (rpm) to 50 ml. The concentrated extract was kept in a beaker covered with 2 layers of aluminum foil and was labelled appropriately. The extract was then transferred into an evaporating dish, covered with poked aluminum foil and further dried using a water bath until a semi solid state was formed. The final extract was stored in another beaker covered with aluminum foil and refrigerated at 4°C until further analysis. Then, the percentage yield of the extraction was calculated.74

The formula is as follows:

The extract was evaporated using rotary evaporator and was further dried using water bath

Phytochemical screening of fruit extract

The maceration extract was subjected to various preliminary tests to determine the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds and tannins, saponins, terpenoids, proteins and amino acids, starch, carbohydrates and quinones.75 The results of the test were observed and recorded accordingly.

Wagner’s test: 2 drops of Wagner’s reagent were added to 1.0 ml of the extract.

A reddish-brown residue was formed in the extract. This indicated a positive test for alkaloids.

Dragendorff’s Test: 2 drops of Dragendorff’s reagent were added to 1.0 ml of the extract.

A reddish-brown precipitate was formed in the extract. This confirmed the presence of alkaloids.

Lead acetate test: 3 drops of 10% lead acetate solution was added into 2.0 ml of the extract.

A yellow precipitate was formed in the extract. This indicated flavonoid content was present.

Ferric chloride test: 3 drops of ferric chloride solution were added to 2.0 ml of the extract.

A dark violet color solution is formed in the extract. This showed the presence of phenolic compounds or tannins.

Foam test: 1.0 ml of the extract was shaken together with 5.0 ml of sodium bicarbonate solution vigorously.

A persistent froth or foam formed in the extract after shaking. This indicated that saponins are present.

Salkowski test: 2.0 ml of chloroform (CHCl3) was added into 1.0 ml of the extract. Then 2.0 ml concentrate sulfuric acid was added carefully into the extract.

A reddish-brown coloration at the interface was formed. This confirmed the presence of terpenoids.

Biuret test: 2.0 ml of sodium hydroxide and 2 drops of copper sulphate solution was added to 1.0 ml of the extract.

There was no color change in the extract. This indicates a negative result of proteins.

Ninhydrin test: 2 drops of Ninhydrin solution was added to 1.0 ml of the extract and mixture was heated for 5 minutes using a water bath.

There was no color change in the extract. This confirms that amino acids were not present.

Iodine test: 3 drops of iodine solution were added to 1.0 ml of the extract.

There was no color change formation in the extract. This indicates that there was no starch present in the extract.

Benedict’s test: 2.0 ml of Benedict’s reagent was added to 2.0 ml of the extract and heated in a water bath for 5 minutes.

A brick-red precipitate was formed in the extract. This indicated a positive test for reducing sugars.

Molisch’s test: 2 drops of α-naphthol were added to 2.0 ml of the extract, then add 1.0 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid slowly along the inner side of the test tube.

A violet ring appeared at the interface. This showed the presence of carbohydrates.

3 drops of concentrated hydrochloric acid were added to 1.0 ml of the extract.

A yellow precipitate formed indicated the presence of quinones.

Antioxidant determination activity

DPPH Free radical scavenging assay

The free radical scavenging capacity of Actinidia chinensis was assayed using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method. A 0.1 mM stock solution of DPPH was prepared using concentration of 2.5 mg/mL in ethanol. Maceration extract at different concentrations and control (ethanol, without extract) were added into individual test tubes. 1.0 ml of each extract and control were mixed with 2.0 ml of ethanolic solution of DPPH reagent. The mixture was shaken to ensure proper mixing and left to stand in the dark at room temperature for a duration of 30 minutes. Later, the light absorbance of the mixture was measured against a blank at 517 nm with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. All the steps above were repeated for BHT reagent for different concentrations. BHT reagent was used as a reference standard. The data for maceration extract and reference standard was collected and tabulated. The 50% inhibitory concentration value (IC50) for the extract was calculated by plotting a linear regression graph, with lower inhibition percentage indicating greater antioxidant potency.

The formula for calculating the percentage inhibition of DPPH radical is Kumar Bhandary et al.,76: % inhibition = [(A0 - A1) / A0] x 100

Where A0 is the absorbance of the standard and A1 is the absorbance of the DPPH solution mixed with sample extract.

Dilution for DPPH scavenging activity

Maceration extract:

BHT reagent (reference standard)

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted to identify the functional groups present in the extract and provide qualitative evidence of its phytochemical compounds. Actinidia chinensis extract was analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy using a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer with an ATR sampling accessory. To ensure measurement accuracy, the crystal surface was thoroughly cleaned with isopropyl alcohol (IPA), followed by 70% ethanol using lint-free wipes before starting sample analysis. Then one drop of the extract was directly deposited onto the ATR crystal using a spatula. Spectral data was acquired across the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with a spectral resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. The recorded spectra was analyzed by comparing the peaks to reference spectra to identify specific phytochemicals.

Phytochemical screening

Results of phytochemicals present in ethanolic extract of maceration process is shown in Table 2.

|

No |

Phytochemical screening tests |

Results |

|

1 |

Alkaloids |

+ |

|

2 |

Flavonoids |

+ |

|

3 |

Phenolic compounds or Tannins |

+ |

|

4 |

Saponins |

+ |

|

5 |

Terpenoids |

+ |

|

6 |

Proteins and amino acids |

- |

|

7 |

Starch |

- |

|

8 |

Carbohydrates |

+ |

|

9 |

Quinones |

+ |

Table 2 Results of phytochemicals present in ethanolic extract of maceration process

+ Present, - Absent

Antioxidant activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The following results shows the absorbance and percentage scavenging value of maceration extract and BHT reagent along with graphs of IC 50% calculated as mentioned in Table 3. Each maceration extract concentration with its percentage scavenging in Table 4.

|

Sample Concentration (µg/mL) |

Absorbance (WL517nm) |

|

Control |

0.75 |

|

50 |

0.535 |

|

100 |

0.432 |

|

250 |

0.248 |

|

500 |

0.139 |

|

1000 |

0.068 |

Table 3 Each maceration extract concentration with its absorbance value

|

Sample Concentration (µg/mL) |

Percentage scavenging (%) |

|

50 |

28.67 |

|

100 |

42.4 |

|

250 |

66.93 |

|

500 |

81.47 |

|

1000 |

90.93 |

Table 4 Each maceration extract concentration with its percentage scavenging

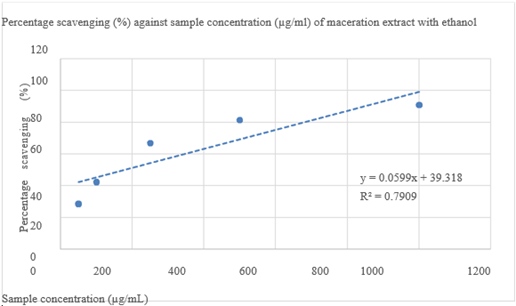

Percentage scavenging (%) against sample concentration (mg/mL) of maceration extract with ethanol is given in Figure 6. Each BHT reagent concentration with its absorbance value and each BHT reagent concentration with its percentage scavenging shown in Table 5.

Figure 6 Percentage scavenging (%) against sample concentration (mg/mL) of maceration extract with ethanol.

|

Sample Concentration (µg/ml) |

Absorbance (WL517nm) |

Percentage scavenging (%) |

|

Control |

0.75 |

|

|

50 |

0.521 |

30.53 |

|

100 |

0.426 |

43.2 |

|

250 |

0.202 |

73.07 |

|

500 |

0.113 |

84.93 |

|

1000 |

0.039 |

94.8 |

Table 5 Each BHT reagent concentration with its absorbance Sample Concentration (µg/ml)

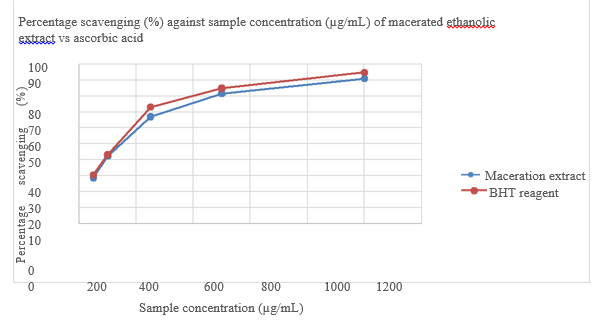

Percentage scavenging (%) against sample concentration (ug/mL) of BHT reagent is shown in Figure 7 and Comparison of percentage scavenging (%) of maceration ethanolic extract vs BHT reagent in given in Table 6. While Comparison of IC 50 of maceration ethanolic extract vs BHT reagent is shown in Table 7. Figure 8 shows the Percentage scavenging (%) against sample concentration (µg/mL) of macerated ethanolic extract vs Ascorbic acid. FTIR spectrum of Actinidia chinensis is shown in Figure 9. Table 8 gives FTIR spectral peak values and functional groups of Actinidia chinensis extract. Comparison between FTIR spectral peak values of Actinidia chinensis extract with Quercetin and Catechin is shown in Table 9.

Figure 8 Percentage scavenging (%) against sample concentration (µg/mL) of macerated ethanolic extract vs Ascorbic acid.

|

Sample Concentration (µg/ml) |

Percentage scavenging (%) |

|

|

Maceration |

BHT reagent |

|

|

50 |

28.67 |

30.53 |

|

100 |

42.4 |

43.2 |

|

250 |

66.93 |

73.07 |

|

500 |

81.47 |

84.93 |

|

1000 |

90.93 |

94.8 |

Table 6 Comparison of percentage scavenging (%) of maceration ethanolic extract vs BHT reagent

|

Sample type |

IC 50 (µg/mL) |

|

Maceration |

178.33 |

|

BHT reagent |

133.08 |

Table 7 Comparison of IC 50 of maceration ethanolic extract vs BHT reagent

|

Spectrum no. |

Wave number (cm⁻¹) |

Wave number Range (cm⁻¹) |

Functional group Assignment |

Predicted compound |

|

1 |

3290 |

3200–3550 |

O–H stretching (hydroxyl group) |

Phenolic compounds and flavonoids |

|

2 |

2931 |

2850–2950 |

C–H stretching (methylene group) |

Sugars, fatty acids and glycosides |

|

3 |

1715 |

1690–1750 |

C=O stretching (carboxylic acids/ketones) |

Organic acids |

|

4 |

1634 |

1600–1650 |

C=C stretching (aromatic ring) |

Flavonoids |

|

5 |

1403 |

1350–1450 |

C–H bending (methyl groups) |

Alcohol, phenols, and glycosides |

|

6 |

1232 |

1200–1270 |

C–O stretching (esters) |

Alcohol, phenols, and glycosides |

|

7 |

1030 |

1000–1100 |

C–O or C-O-C stretching (alcohol, esters, and ethers) |

Glycosidic linkage in flavonoid conjugates or carbohydrate derivatives |

|

8 |

775, 816 |

750–900 |

C–H bending (aromatic ring out-of- plane) |

Aromatic and polyphenolic structures |

Table 8 FTIR spectral peak values and functional groups of Actinidia chinensis extract

|

Spectrum no. |

Wave number (cm⁻¹) A. chinensis |

Wave number (cm⁻¹) Quercetin |

Wave Number (cm⁻¹) Catechin |

Functional Group Assignment |

|

1 |

3290 |

3283 |

3412 |

O–H stretching |

|

2 |

1715 |

1666 |

- |

C=O stretching |

|

3 |

1634 |

1610 |

1610 |

C=C stretching |

|

4 |

1403 |

1317 |

1474 |

C–H bending |

|

5 |

1232 |

1200 |

1285 |

C–O stretching |

|

6 |

1030 |

1165 |

1020 |

C–O or C-O-C stretching |

|

7 |

816 |

820 |

965 |

C–H bending (aromatic ring out-of-plane) |

Table 9 Comparison between FTIR spectral peak values of Actinidia chinensis extract with Quercetin and Catechin

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

The FTIR spectrum of Actinidia chinensis in Figure 4.3.1 displayed several characteristic peaks that matched functional groups known to be present in bioactive phytochemicals. Based on the FTIR data, various wavelengths including 775, 1030, 1232, 1403, 1634, 1715, 2931, 3290 cm⁻¹ were observed. In region between 3000-3500 cm⁻¹, a wide and broad peak is found at 3290 cm⁻¹. It is a characteristic of O-H stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups that are predominantly found in phenolic compounds and flavonoids.77 Another small peak at 2931 cm⁻¹ reflected C–H stretching in aliphatic chains, which reveals the presence of methylene group. This region supported the existence of carbohydrate derivatives or long-chain phytoconstituents like sugars, fatty acids and glycosides. Additionally, the appearance of 1715 cm⁻¹ absorption band is due to C=O (carbonyl) stretching, would indicate carboxylic acids or ketones present. The detection of carbonyl groups is often associated with organic acids such as ascorbic acid or citric acid, which contributes to its antioxidant activity. One more important peak observed at 1634 cm⁻¹ revealed C=C stretching vibrations found in aromatic rings.78 This characteristic strongly indicated the presence of flavonoid compounds in the extract, in which it reflected the conjugated π-electron system found in quercetin and catechin constituents. Aside from that, sharp peaks at 1403 cm⁻¹ and 1232 cm⁻¹ suggest C–H bending and C–O stretching, respectively, further confirming the presence of alcohols, phenols, and glycosides. This is supported by the appearance of a broad peak at region 1030 cm⁻¹ which corresponds to C– O or C-O-C stretching vibrations, indicating that alcohols, esters, and ethers are likely to be present. It can be inferred that there is glycosidic linkage in flavonoid conjugates or the existence of carbohydrate derivatives in the extract. Lastly, peaks observed at 775 cm⁻¹ and 816 cm⁻¹ could suggest aromatic ring deformations, which confirms the existence of aromatic and polyphenolic structures.

The objective of this research is to determine the phytochemical constituents, antioxidant potential, and characterization of quercetin and catechin in Chinese gooseberry (Actinidia chinensis) using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Qualitative phytochemical screening, quantitative DPPH antioxidant assay, and FTIR analysis were the three main approaches employed in this study. Maceration method was used for the extraction process by using 95% ethanol as solvent. The preliminary phytochemical screening of the extract revealed the presence of various bioactive classes of compounds. The positive results for alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, and carbohydrates in Actinidia chinensis extract can conclude that it is rich in a wide variety of phytochemical compounds, especially flavonoids which have medicinal benefits.25,27,30,32 These results were consistent with previous studies, including Mulye et al.,65 and Salama et al.,11 who also reported the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins and terpenoids in Actinidia deliciosa, supporting the idea that kiwi fruits from various species contain similar classes of phytochemicals. On the other hand, the tests for proteins, amino acids, and starch were negative.

In fact, there were various phytochemical compounds present in Actinidia chinensis highlighted in previous research.7,12,13–15 Nevertheless, this study only showed the presence of a few. The absence in phytochemical tests were expected due to either inefficient extraction with the use of 70% ethanol as solvent, or low concentration of the protein and starch in ripe Actinidia chinensis. Next, the antioxidant potential of Actinidia chinensis extract was assessed using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay. The A. chinensis extract exhibited strong antioxidant activity, increasing with concentration by rising from 28.67% at 50 µg/mL to achieving 90.93% scavenging at 1000µg/mL. BHT achieved higher values of exhibiting percentage inhibition of 30.53% at 50 µg/mL and reached up to 94.80% at 1000µg/mL. This is consistent with similar strong DPPH radical inhibition (>90%) observed in A. arguta varieties in studies conducted by Zhang et al.48 Based on Table 4.2.1.5, all concentrations for extract and standard reference showed dose-dependent increase in percentage antioxidant activity. This is supported by Ozen et al.,79 that observed a concentration-dependent antioxidant response in their extract and significantly enhanced DPPH radical scavenging activity at higher concentrations.

The calculated IC₅₀ value was found to be 178.33 µg/mL for A. chinensis extract and 133.08 µg/mL for BHT reagent reference standard. The results indicated that the synthetic antioxidant BHT demonstrated stronger antioxidant potency under the same assay conditions. A smaller IC₅₀ value means the substance is more effective, as BHT required a smaller concentration to inhibit 50% of DPPH radicals compared to the extract. Nevertheless, the extract showed moderate antioxidant activity with IC₅₀ value closely comparable to the reference standard and demonstrating strong DPPH radical scavenging activity of 90.93% at 1000µg/mL. The enhanced radical scavenging activity could be due to the presence of complex bioactive constituents present in the fruit, including flavonoids or phenolic compounds, as confirmed by phytochemical screening and FTIR analysis. This strong antioxidant activity correlates well with the results from preliminary phytochemical screening, which confirmed the presence of flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and tannins etc. These results support the conclusion that A. chinensis is a rich source of natural antioxidants.

Finally, FTIR analysis of Actinidia chinensis was conducted and the spectrum obtained was analyzed. Although pure standards of quercetin and catechin were not available for direct FTIR analysis in this study, comparison was made using reference FTIR spectra from previous studies done by Yaneva et al.,80 and Catauro et al.81 Comparison of the FTIR spectrum of the kiwi extract with standard reference spectra of catechin and quercetin reveals several matching peaks. The broad O–H stretch observed at 3290 cm⁻¹ corresponds well with those found in quercetin (3283 cm⁻¹) and catechin (3412 cm⁻¹), suggesting the presence of phenolic hydroxyl groups. A strong peak at 1715 cm⁻¹ indicates C=O stretching, which is close to quercetin’s characteristic band at 1666 cm⁻¹ as it contains a conjugated carbonyl group in its flavonol backbone. Additionally, the spectra revealed peak at 1634 cm⁻¹ matched both quercetin and catechin spectra (1610 cm⁻¹), which confirms C=C stretching vibration that indicates aromatic compounds. Furthermore, similar absorption bands found at 1403 cm⁻¹, 1232 cm⁻¹, and 1030 cm⁻¹ respectively correspond to C–H bending and C–O stretching, which are commonly associated with flavonoid structures. The band at 816 cm⁻¹ was also consistent with quercetin (820 cm⁻¹) and somewhat near catechin (965 cm⁻¹) indicating aromatic ring bending present, which are a core structural component of both quercetin and catechin. When considered alongside the positive results in phytochemical screening for flavonoids and phenolics and the observed DPPH radical scavenging activity, the FTIR findings strongly suggested the presence of catechin and quercetin in the Actinidia chinensis extract.82–86

It is concluded that Chinese gooseberry (Actinidia chinensis) is a fruit rich in bioactive constituents with potential health benefits. Previous studies support its activities in having antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and nutraceutical potential. This study demonstrated that Actinidia chinensis contains a diverse range of phytochemicals, including alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, saponins, terpenoids, and carbohydrates, as identified through preliminary screening. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay has also confirmed that A. chinensis extract exhibited strong radical scavenging activity in a dose-dependent manner, having 90.93% at 1000µg/mL. Aside from that, FTIR spectroscopy has successfully characterized the major functional groups associated with quercetin and catechin, which supports the presence of flavonoids in A. chinensis. Together, these findings validate the potential of Chinese gooseberry as a natural source of antioxidant compounds with promising nutraceutical or therapeutic applications. However, it is believed that these methods were only used as qualitative tools and cannot provide a definitive identification of specific phytochemical compounds in the extract. Therefore, exploring a broader range of analytical methods are encouraged to open new avenues for future research.

In order to deeply investigate the phytochemical composition of Actinidia chinensis, several recommendations are proposed for future research. First of all, it is strongly recommended to use pure reference standards of quercetin and catechin to allow direct comparison between sample extract during FTIR analysis. To accurately confirm the identity of quercetin and catechin, quantitative techniques including High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), HPLC-MS, or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy should be employed for superior specificity in structural verification of individual phytochemicals present within the extract. Other than that, other antioxidant assays, particularly the ABTS radical cation decolorization assay or Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), can be paired in order to broaden the evaluation of antioxidant potential. Moreover, we could explore alternative solvents or extraction techniques such as Soxhlet extraction to improve the yield and range of bioactive compounds, including proteins and starches that were not detected in the current work. It is also possible to investigate other parts of the fruit such as the peel and seeds, which may contain higher concentrations or different profiles of antioxidant compounds compared to the pulp. Hence, it is encouraging to implement these recommendations in future work to enhance comprehensive assessments of Actinidia chinensis as a natural source of antioxidants.

The authors are highly thankful to the Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Bedong, Kedah D.A., Malaysia for funding and providing facilities to carry out this research project in MDL 4.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

©2025 Hua, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.