eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 16 Issue 3

1Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

2Institute of Immunology and Human Genomics, Academy of Sciences, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence: Djabbarova Yu K, Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute; 223 Bogishamol Street, Yunusabad district, 100140, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Tel +998 94 699 64 02

Received: June 15, 2025 | Published: June 26, 2025

Citation: Abduganieva DF, Urinbaeva NA, Djabbarova YK, et al. Diagnostic value of angiogenic growth factors in combined pregnancy complications: preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2025;16(3):104-107. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2025.16.00795

Purpose: to assess the diagnostic significance of angiogenic growth factors in predicting early and late phenotypes of fetal growth restriction (FGR) and in cases of its combination with severe preeclampsia (PE).

Materials and methods: The study included 70 pregnant women, of whom 50 had FGR, including 21 with concurrent FGR and PE. Serum levels of angiogenic growth factors (PlGF, VEGF-A, IGF-1) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results: In early-onset FGR (n = 20), PlGF levels were reduced by 35.2% (p < 0.01), while in late-onset FGR (n = 30), the decrease was 21.0% compared to the control group (n = 20, p < 0.05). VEGF-A expression was significantly reduced by 2.6-fold in early-onset FGR (p < 0.01) and by 1.9-fold in late-onset FGR (p < 0.05). A similar trend was observed for IGF-1 levels.In cases of early-onset FGR combined with severe PE, all three angiogenic markers were significantly lower than in cases of late-onset FGR with PE: PlGF by 1.7-fold, VEGF-A by 1.5-fold, and IGF-1 by 1.6-fold (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: A significant decrease in angiogenic growth factor levels was observed in pregnant women with FGR, most pronounced in early-onset cases and especially when combined with severe early PE. Deficiency of PlGF, VEGF-A, and IGF-1 production appears to be a pathognomonic marker of PE and FGR development.

Keywords: angiogenic growth factors, pregnancy, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia

FGR, fetal growth restriction; PE, preeclampsia, PlGF, рlacental growth factor; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor-A; IGF-1, insulin growth factor-1

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) is a pathological condition in which the fetus fails to achieve the expected weight for its gestational age (below the 10th percentile). Depending on the gestational age, FGR is classified into early-onset (before 32 weeks) and late-onset (after 32 weeks) phenotypes.1,2 These phenotypes differ significantly in terms of prevalence, screening indicators, placental histopathology, Doppler parameters, maternal comorbidities, and pregnancy outcomes.

Despite the availability of numerous diagnostic models based on clinical history, biochemical, ultrasound, and Doppler data, approximately 40% of FGR cases are considered idiopathic, with no identifiable cause.3 The 2024 Green-top Guideline emphasizes the urgent need for novel biomarkers to distinguish between FGR phenotypes and guide optimal pregnancy management.4

Among pregnancy complications associated with FGR, preeclampsia (PE) ranks first.5,6 PE is one of the most serious obstetric complications, posing a significant threat to both maternal and fetal health. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy accompanied by FGR account for up to 26.5% of cases.7 According to M Veglia et al.,8 70% of patients with early-onset FGR also present with maternal hypertension.8 A study by T-H Hung et al.9 reported that FGR occurred in 50.6% of women with early-onset PE and in 25.5% of those with late-onset PE.9 This high frequency of FGR in PE can be explained by the shared pathophysiological mechanisms: defective trophoblast invasion of the spiral arteries and endothelial dysfunction.10,11

According to EP Sakhabutdinova,12 severe PE is associated with a 2.8-fold higher incidence of FGR compared to moderate PE (42.6±7.2% vs. 15.3±3.6%; p < 0.001). In the second trimester, 25.5% of women with severe PE were diagnosed with FGR—five times more often than those with moderate PE (5.1%).12 KT Muminova13 notes that FGR is strongly associated with severe PE: its incidence was 60% in early-onset severe PE, 40% in late-onset, and 35% in PE combined with chronic hypertension.13 K Rotshenker-Olshinka et al.14 reported a 20% recurrence risk of FGR in women with PE and a history of delivering growth-restricted newborns.14

Among all gestational complications, PE has the most profound impact on pregnancy outcomes for both mother and fetus.15 Comprehensive clinical and morphological studies have demonstrated that the progression of PE is accompanied by concentric vascular remodeling, wall thickening, lumen obliteration, and reduced capillary density in terminal villi, leading to increased vascular resistance, impaired placental exchange, and placental insufficiency.16

A key role in the pathogenesis of FGR is attributed to abnormal placentation, including impaired angiogenesis and insufficient vascular remodeling in the uteroplacental complex. These processes are regulated by angiogenic growth factors. One of the critical goals in reducing perinatal mortality remains the development of risk stratification algorithms for FGR, as well as the identification of effective biomarkers and laboratory predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes.17,18

A review of recent scientific literature reveals a lack of data on the condition of the mother–placenta–fetus system in FGR, particularly in pregnancies complicated by hypertensive disorders. The development of preclinical diagnostic approaches and effective preventive strategies remains a key challenge in modern perinatology.

Objective

To evaluate the diagnostic significance of angiogenic growth factors in predicting early and late phenotypes of fetal growth restriction (FGR), including cases complicated by severe preeclampsia (PE).

A total of 70 pregnant women were examined: 20 with early-onset FGR (22–31 weeks), 30 with late-onset FGR (32–38 weeks), and 20 with physiologic pregnancy (control group).

Inclusion criteria: gestational age over 22 weeks; complicated pregnancy course with fetal growth restriction (FGR); presence or absence of mild and severe preeclampsia; informed consent from the patient. Exclusion criteria: severe endocrinopathies; congenital or acquired heart and vascular defects; decompensation of vital organs (renal or hepatic failure); acute infections (including HIV, COVID-19); congenital fetal malformations.

Serum levels of angiogenic growth factors (PlGF, VEGF-A, IGF-1) were measured at the Laboratory of Reproductive Immunology, Institute of Immunology and Human Genomics, Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan (Director: Academician T.U. Aripova). The analysis was performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with commercially available kits from Vector-Best (Russia), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The data were processed using nonparametric statistical methods, including calculation of the mean (M), standard deviation (σ), standard error (m), and relative values (percentages). Statistical significance of intergroup differences was assessed using Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p< 0.05.

The study was conducted at the Republican реrinatal сenter (Tashkent, Uzbekistan; Director: Prof. N.A. Urinbaeva, MD, PhD). The majority of participants were in their reproductive prime (20–30 years of age), comprising 65.0% and 76.7% of the study group. Parity was similar between groups; however, multiparous women were present only in the FGR group (10.0%).

The leading risk factors for FGR included chronic arterial hypertension (58.6%), iron deficiency anemia (52.9±6.0%), early severe PE (85.7%), and early-onset placental insufficiency of predominantly severe grade (90.0%).19 According to ultrasound findings, most patients exhibited FGR of grade II severity.

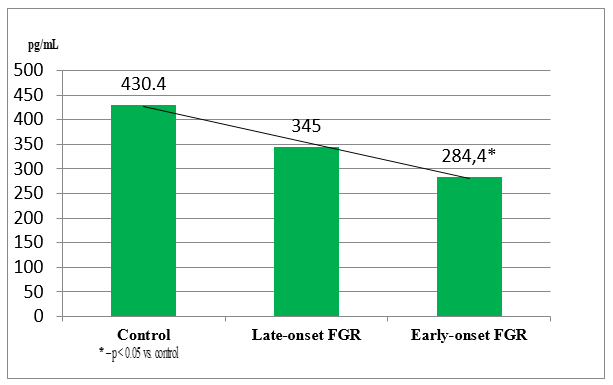

Serum levels of placental growth factor (PlGF), stratified by gestational age, are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Placental growth factor (PlGF) levels in pregnant women depending on gestational age at FGR onset.

The data analysis revealed that PlGF levels were significantly reduced in FGR cases: by 33.9% in early-onset FGR (p < 0.01) and by 19.8% in late-onset FGR (p < 0.05), compared to the control group. According to literature, PlGF promotes proliferation of extravillous trophoblasts and synergistically enhances VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability.

According to V Giorgione et al.,20 PlGF levels are lower in pregnancies complicated by placental growth restriction.20 Our findings support this, indicating that reduced PlGF expression is strongly associated with FGR development, in line with previous studies by KhA Akramova and DI Akhmedova.17 The observed correlation between PlGF levels (<100 pg/mL) and FGR incidence highlights its potential role as a marker of impaired second-wave trophoblast invasion.

Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) stratified by gestational age, are presented in Figure 2.

VEGF-A levels were significantly reduced in early-onset FGR (2.5-fold; p<0.01) and late-onset FGR (1.8-fold; p<0.05). VEGF-A is a key angiogenic molecule responsible for neovascularization and endothelial permeability. According to NR Akhmadeev,18 VEGF <95.5 pg/mL allows differentiation between FGR and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) fetuses.18 In contrast, EV Ulyanina21 reported that VEGF ≥95.5 pg/mL indicates risk of FGR, while levels ≥197 pg/mL predict adverse outcomes.21 In our study, VEGF <60 pg/mL at 22–27 weeks may indicate a high risk of decompensated placental insufficiency and early-onset FGR.

A similar pattern was observed for IGF-1 (Figure 3). The lowest concentration was detected in early-onset FGR (22–31 weeks), with levels of 41.0 pg/mL—44.4% lower than controls (p<0.001) and 29.7% lower than in late-onset FGR (p<0.001). In late-onset FGR, IGF-1 remained significantly lower than control by 21.0% (p<0.001).

IGF-1 plays a key role in fetal trophism by regulating glucose and amino acid transport across the placenta, and it promotes mitogenesis and cell proliferation. Its deficiency contributes to impaired fetal growth.22 According to TV Tarabrina,23 low IGF-1 is a predictor of severe FGR.23 Our data suggest that IGF-1 <50 pg/mL at 22–27 weeks may serve as an early marker of FGR.

The VEGF-A/IGF-1 ratio was 1.16 in early-onset FGR and 1.10 in late-onset cases, further reflecting the severity of angiogenic imbalance.

Evaluation of diagnostic performance revealed that VEGF-A had absolute specificity (Sp = 100%) in detecting both early and late FGR. IGF-1 testing had sensitivity exceeding 72% and the highest specificity (86.6%) in early-onset cases.

In pregnancies complicated by severe PE, angiogenic factor levels were significantly lower in early-onset FGR compared to late-onset, particularly for PlGF and IGF-1 (Table 1), suggesting more pronounced angiogenic deficiency in early forms of the disorder.

|

Growth factor, pg/mL |

Early-onset FGR |

Late-onset FGR |

||

|

FGR, n=20 |

FGR + PE, n=11 |

FGR, n=30 |

FGR + PE, n=10 |

|

|

PLGF |

284,41±44,47 |

92,0±24,2a^ |

344,95±34,89 |

159,4±33,33c |

|

VEGF A |

46,48±1,35^ |

47,18±2,1^ |

63,99±2,10 |

68,1±3,10 |

|

IGF 1 |

40,99±3,59^ |

35,82±3,6^ |

58,28±3,58 |

56,2±6,5 |

Table 1 Levels of angiogenic growth factors in severe preeclampsia stratified by FGR phenotype

Note: a – p<0.05, the difference is significant in relation to the similar average indicator of early-onset FGR;

^ – the difference is significant in relation to the similar indicator of late- onset FGR;

c – the difference is significant in relation to the similar average indicator of late- onset FGR

The presented data indicate that the combined complication of pregnancy in the form of fetal growth restriction (FGR) and severe preeclampsia (PE) is associated with a more pronounced decrease in angiogenic growth factors. In early-onset PE with early-onset FGR, the level of PlGF was 3.1 times lower than the mean value for isolated FGR of the same gestational age (p<0.001). The expression levels of VEGF-A and IGF-1 did not differ significantly from the early- onset FGR group without PE (p>0.05).

Among women with late-onset FGR and PE (after 32 weeks), a significant reduction in PlGF was also observed—2.2 times lower than in isolated late-onset FGR (p<0.05). When comparing angiogenic marker levels between early- onset and late- onset FGR phenotypes complicated by PE, all three markers were significantly lower in the early-onset group: PlGF by 1.7 times, VEGF-A by 1.5 times, and IGF-1 by 1.6 times (p<0.05), suggesting more profound and earlier disruption of placentation.

Thus, marked reductions in PlGF (<100 pg/mL), VEGF-A (<50 pg/mL), and IGF-1 (<40 pg/mL) may be considered pathognomonic markers of severe PE and FGR. According to several studies,24 measurement of circulating pro- and anti-angiogenic factors can predict the onset of PE several weeks before clinical manifestation.

The study confirmed that in addition to ultrasound fetometry, determining the levels of angiogenic growth factors (PlGF, VEGF-A, IGF-I) enables prediction of FGR and assessment of its severity. A significant decrease in these parameters was found in pregnant women with FGR, especially in early-onset cases. Disruption of these growth factors reflects pathological placental changes leading to placental insufficiency and subsequent fetal growth restriction.

Considering the high sensitivity and specificity of immunological assays, the measurement of VEGF-A and IGF-I levels, and their ratio (≤1.2), may be recommended as biomarkers for early detection and prediction of FGR.

Based on literature data25 and our findings, preconceptional preparation is necessary for women at high risk of developing FGR. This includes correction and management of chronic somatic and inflammatory conditions; administration of estrogen-progestin therapy for 6 months to ensure contraception, optimal intergenetic interval, and proper endometrial development. Upon pregnancy onset, early use of gestagens is advisable to support decidualization and development of the placental complex and to prevent angiogenesis disorders.

Based on the above, we developed a management algorithm for high-risk pregnant women both in the preconception and gestational periods (Figure 4).

A significant reduction in angiogenic growth factors is observed in pregnancies complicated by FGR, particularly in early-onset forms of the disorder.

Deficiencies in PlGF, VEGF-A, and IGF-1 serve as pathognomonic markers of severe preeclampsia and FGR.

The VEGF-A/IGF-1 ratio may be recommended as an additional predictor for the early detection and risk stratification of fetal growth restriction.

Implementation of preconception care, early antenatal follow-up, and subclinical diagnosis of FGR aims to ensure physiological pregnancy progression, optimal fetal growth, and reduced perinatal complications, thus improving maternal and neonatal outcomes. However, further large-scale studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of this approach.

None.

Author consent

All authors give consent for publication.

Ethics Approval

All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

The authors of this article confirm the lack of financial or any other support that needs to be reported.

The authors confirm the absence of any other conflict of interest that needs to be reported.

©2025 Abduganieva, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.