MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 2

1Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Inc, 351 Hospital Road Suite 415 Newport Beach, USA

2Newport Irvine Surgical Specialists, 510 Superior Ave #200g, Newport Beach, USA

3Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian, One Hoag Drive, Newport Beach, USA

Correspondence: Brian P Dickinson MD, Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Inc, 351 Hospital Road Suite 415 Newport Beach, CA 92663, USA

Received: March 23, 2025 | Published: July 4, 2025

Citation: Le K, Marashi N, Nguyen E, et al. Incision choice for complicated ventral hernia patients an OVIO 360 degree photo comparison: a case report.? MOJ Surg. 2025;13(2):53-57. DOI: 10.15406/mojs.2025.13.00294

Background: The senior authors have previously published on abdominal wall reconstruction using Strattice acellular dermal matrix demonstrating effective aesthetic and functional results. As our experience increases, we are often faced with more challenging hernias as well as more complex patients.

Purpose: To demonstrate a simple incision pattern that can be used in complex medical patients and patients with a high body mass index.

Methods: A retrospective chart review was performed on our patient who underwent an abdominal wall reconstruction of a ventral incisional hernia with component separation and placement of Strattice acellular dermal matrix. The patient is a tall male with a high body mass index and a history of cirrhosis complicated by ascites.

Results: Strattice acellular dermal matrix was successfully used in an underlay fashion to reinforce a midline hernia repair. A vertical and horizontal cross-four pronged star incision was used to gain access to the abdominal wall to preserve the venous drainage of the superficial epigastric and circumflex systems. These are often dominant arterial and venous angiosomes of the abdominal wall and offer the benefit of dependent venous drainage.

Conclusion: Successful repairs of primary and recurrent abdominal hernias with Strattice acellular dermal matrix are effective. Based on our experience, for patients with a high body mass index who are at increased risk of seroma formation and skin necrosis, utilizing a combined vertical and horizontal cross incision for exposure can help minimize complications and optimize aesthetic outcomes.

Keywords: ventral hernia, recurrent hernia, abdominal wall reconstruction, component separation, acellular dermal matrix, strattice, 360 degree photo imaging

IV, intravenous; JP, jackson-pratt; BMI, body mass index

The senior authors have previously published on abdominal wall reconstruction using Strattice acellular dermal matrix with acceptable aesthetic and functional results.1,2 Our objective was to restore the form and function of the abdominal wall while minimizing recurrences and complications. As the population ages and comorbidities such as obesity, pulmonary disease, DVT, cardiac disease, liver disease, and recurrent hernias rise, the complexity of hernia repairs and their post-operative management increases.

We previously published on the “load sharing” principle of abdominal wall reconstruction.1 In our discussions with general surgeons, common questions that arise are “where do you put your incision?”, “how far do we undermine?”, and “what do you do with excess skin?”. In this study we demonstrate, through photographs and illustrations, how to successfully design skin flaps so that general and plastic surgeons at the start of their careers can successfully tackle complicated ventral incisional hernias.

One of the most important pearls when choosing to repair these complex hernias is to have a comprehensive discussion of all the potential complications that may arise. Specifically, emphasis should be placed on the risk of seroma, hematoma, skin, necrosis, ileus, DVT, and the potential need for re-operation to address any of the above complications. Many of these patients experience weight loss before surgery and continue to lose weight afterwards due to increased metabolic demands for healing and a relative reduction in the abdominal domain, which leads to early satiety. Consequently, they may require additional skin removal procedures similar to those performed in patients who have undergone massive weight loss. We present our methodology below.

A retrospective chart review was conducted on a patient who underwent component abdominal wall reconstruction and Strattice acellular dermal matrix repair of a ventral hernia placed in the intraperitoneal space by the authors. The pre- and post-operative CT-scans were compared to evaluate satisfactory anatomical surgical repair. Before and after 360 degree photos were examined and charts were reviewed for complications. The participant provided written consent for their use of photographs for presentation and publication.

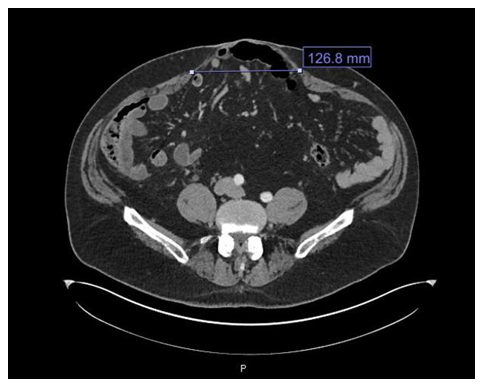

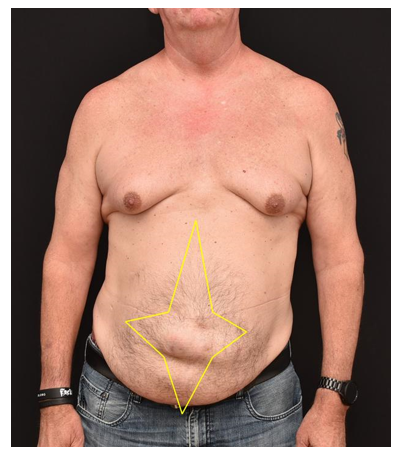

A 56 year old male with a history of colectomy and cirrhosis presented to us with a large ventral hernia. The patient was 6’4” 280 lbs on initial presentation but underwent successful weight-loss with Mounjaro and a disciplined diet. Prior to the surgery, the patient's weight decreased to 218 lbs. over the course of one year yielding a body mass index of 29. Over the course of one year (Figure 1) (Video 1). The hernia started above the umbilicus and extended below the level of the umbilicus.

Figure 1 Pre-operative Ovio 360 degree photo analysis showing a large incisional ventral hernia from prior colectomy.

A preoperative CT-scan of the abdomen and pelvis showcased a midline ventral hernia at the level of the umbilicus and width of the hernia at its widest part was 12 cm. The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus muscles were relaxed and not in a taut position (Figure 2). A preoperative nasal swab tested positive for methicillin-resistant Staph aureus, and the patient was given a decolonization with mupirocin ointment to the external nares twice a day for seven days and a Hibiclens shower daily for 7 days before surgery.

Figure 2 Preoperative CT scan at a level just below the umbilicus showing a broad-based ventral hernia containing nondilated loops of small bowel and colon. The distance between the edges of the rectus muscle was approximately 12 cm in length.

Given the patient’s BMI, history of cirrhosis, recent weight loss with Mounjaro usage, and a positive methiciclin sensitive staph areus (MSSA) swab, we anticipated a high complication rate. To mitigate abdominal wound complications, the patient was placed on a diet of 100 grams of protein daily for 6 weeks prior to surgery, 2 sessions of hyperbaric oxygen therapy prior to surgery, and a bowel prep with a 48-hour clear liquid diet prior to surgery.

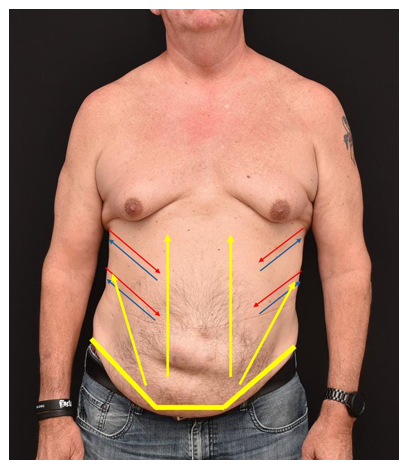

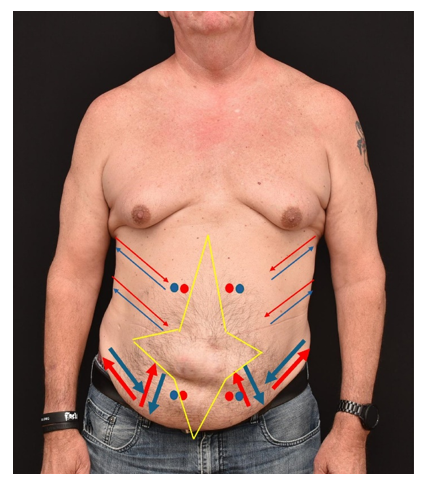

To further mitigate the abdominal wound complications, great care was taken in planning our incision to preserve as much blood supply to the abdominal wall, gain traction-less exposure, and minimize subcutaneous dead space fluid accumulation (Figure 3). A four pronged star pattern incision reducing both a vertical and horizontal dimension was used to preserve the inferior and dependent venous drainage system of the superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex vessels of the abdominal wall to prevent seroma and wound healing complications.

Figure 3 A four pronged star pattern was used to plan the skin excision and exposure. This skin pattern most importantly preserved the superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex venous system which drains dependently into the lower abdomen and groin.

This pattern facilitates venous drainage and likely lymphatic drainage and minimizes seroma risk as well as venous congestion of skin flaps (Figure 3).

The operation commenced with the patient on an octreotide drip to decrease splanchnic blood flow in anticipation of large omental and body wall veins as the patient had a history of prior gastric varices and both endoscopic ablation and transvenous coiling. The mid rectus deep inferior epigastric perforators were large given the history of portal hypertension, these were double ligated with medium hemoclips upon raising the skin flaps from the abdominal wall. The skin flaps were raised to gain exposure to the entire hernia as well as the superior and inferior limits of the rectus abdominis muscle.

Extra thick strattice acellular dermal matrix was placed intraperitoneally and fixed with transfascial sutures spanning through the external oblique aponeurosis. The edges of the rectus muscle were then approximated using 0 Nurolon suture interrupted figure of 8 sutures from the xiphoid process to the superior edge of the hernia. The muscle was also approximated from the pubis toward the inferior edge of the hernia with 0 Nurolon.

The patient had an uneventful course with no elevation in wbc count, infection, or seroma. Octreotide was used to prevent body wall and omental vein bleeding intra and postoperatively. A postoperative ileus resolved at 6 days post-operatively. The patient was followed closely by consultations from the medicine, infectious disease and renal teams. Bumex was administered postoperatively on day 4 for diureses to help with both bowel wall and peripheral edema from fluid overload. The only postoperative complication was a deep arm vein DVT at a location of a peripheral IV which resolved with removal of the IV and Eliquis therapy that was initiated at approximately 10 days postoperatively when we felt JP drain outputs had decreased and been removed and hematocrit was stable. The patient completed 3 sessions of hyperbaric oxygen therapy post-operatively to complete his package of 5 sessions.

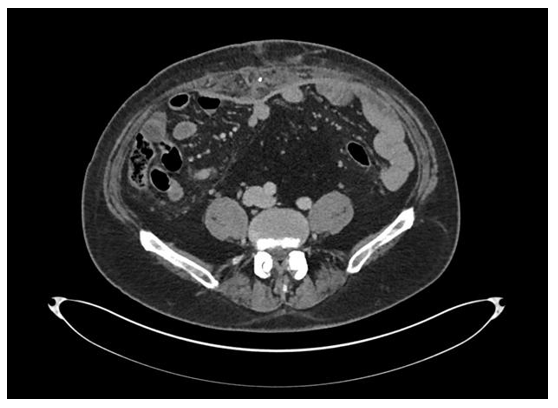

A postoperative CT-scan obtained 4 weeks postoperatively showed satisfactory repair of the hernia with re-approximation of the rectus abdominis muscles in the midline and an underlay of Extra Thick Strattice acellular dermal matrix (Figure 4). A postoperative Ovio 360 degree photo analysis demonstrated an excellent result with anatomical repair of the hernia defect and no evidence of redundant skin in either the vertical or horizontal dimensions (Figure 5) (Video 2).

Figure 4 Post-operative CT scan obtained at approximately 4 weeks postoperatively demonstrated anatomic repair of the hernia with excellent approximation of the rectus abdominis muscles in the midline. The Strattice acellular dermal matrix could be seen in the underlay position and with great apposition against the abdominal wall.

Abdominal wall reconstruction continues to be a challenging aspect of both general and plastic surgery. As our experience with abdominal wall reconstruction evolves, we are often confronted with more challenging cases in patients with more comorbidities. . Morbidly obese male patients remain a formidable demographic. Furthermore, comorbidities, such as pre-existing liver disease, provide an additional set of complications.

One of the most effective pre-operative measures to reduce complication rates is to lower the patient's BMI. With the advent of powerful medications, like Mounjaro, Wegovy, etc, the necessary weight loss can be effectively achieved. Additionally, we feel that cardiovascular exercise and weightlifting are helpful adjuncts to weight loss; although, lifting weights is often avoided in the ventral hernia population secondary to pain. In our patient, his BMI at presentation was 35.9 kg/m^2, which he lowered to 28 kg/m^2 with the use of Wegovy. The decrease in BMI lowered our patient's position from the “Obese” category to the “Overweight” category.

Another helpful step to reduce complications is to maintain adequate arterial and venous blood supply to the skin flaps and eliminate subcutaneous dead space. Paying close attention to this can decrease the seroma rate and hence decrease postoperative cellulitis and abscess formation. Photographic analysis and understanding the location of prior surgical scars can assist in planning the pre-operative exposure approach.

One of our favorite exposure patterns is the standard abdominoplasty incision. This incision starts approximately 6-8 cm above the vulvar commissure in a female or 6-8 cm above the penile shaft in a male. The incision then extends bilaterally in a curvilinear fashion in a skin fold to the level just below the iliac crest bilaterally. The skin and subcutaneous tissue is then elevated to the costal margin bilaterally and the umbilicus when possible is left attached on the abdominal wall. In a majority ventral incisional hernia, the origin is in or in close proximity to the umbilicus and the umbilicus becomes thin and attenuated. In these cases the umbilicus is removed as trying to save it leaves a devascularized stalk and a high rate of infectious complications. While the skin pattern is aesthetic, it is challenging in tall, overweight, males as the resulting skin flap can have venous congestion and result in significant shear and seroma formation (Figure 6). The deep inferior epigastric perforating vessels are also sacrificed when using this skin pattern that contribute a significant arterial and venous blood supply to the abdominal wall. This large dead space and potential thick abdominal flap in a male can create a significant amount of shear and seroma formation. The seroma can yield cellulitis and/or abscess formation with significant postoperative complications and further operations (Figure 7).

Figure 6 Standard abdominoplasty exposure. The yellow lines demarcate the incision pattern. The yellow arrows delineate the extent of skin elevation and dead space formation. The abdominoplasty incision and skin elevation to the costal margins removes the dependent venous drainage of the skin of the abdominal wall.

Figure 7 The four pronged star shaped incision pattern allows access to the abdominal wall. The vertical and horizontal skin incision can reduce potential dead space and prevent seroma formation. This skin pattern allows the superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex systems to effectively drain the lower abdominal skin in a gravity/hydrostatic dependent fashion. The lateral body wall arterial and venous system remains intact as well as the superior and inferior most perforating vessels of the deep inferior epigastric system from the rectus abdominis.

In our experience, the four pronged star pattern can provide adequate exposure to repair the hernia defect while also maintaining skin vasculature and allowing proper skin excision and reduction of dead space in both the vertical and horizontal directions. The skin pattern most importantly preserves the superficial epigastric vessels as well as the superficial circumflex vessels. This allows the lower abdominal skin to be drained in a gravity or hydrostatic dependent fashion. This is in significant contrast to the standard abdominoplasty incision which sacrifices this system and relies on a venous drainage system via the lateral body wall/intercostal system that is not gravity dependent. In the larger patient with thick subcutaneous skin flaps, this can lead to venous congestion of the inferior skin and wound dehiscences. Preserving the superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex systems likely preserves lymphatic drainage concomitantly and significantly reduces seroma formation and its sequelae. If young surgeons or surgeons new in practice are uncomfortable with this skin excision pattern, a vertical and horizontal incision can be made to gain exposure. At the end of the case, when closing, the redundant vertical and horizontal skin excess can be excised in a tailor tack fashion. The resulting skin excision would be four prong star shaped.

Successful hernia surgeries start with careful preoperative preparation as well as attentive post-operative care. Lowering the BMI safely helps mitigate post-operative complications. A protein-dense diet for 6 weeks leading up to the operation, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy pre-and post-operatively, can encourage wound healing and control skin flap edema. Careful pre-operative markings of skin excisions and knowledge of previous abdominal surgeries and skin incisions help optimize blood supply to the abdominal wall and prevent seroma formation. A multidisciplinary approach with other hospital consultants can help identify complications early on, so they can mitigate sequela.3–8

Abdominal wall reconstruction remains a challenge for the reconstructive surgeon. Sound anatomical repair is complex, and the patient population with their inherent comorbidities is difficult. Complications should be expected and managed appropriately. Careful pre-operative planning can help reduce complications and improve aesthetic outcomes.

The authors would like to thank Sundae Zehner and Heather Peffley for her help in these complex reconstructive cases. Sundae and Heather are reliable, dependable, and make these complex reconstructive cases possible.

The authors would also like to thank oVio Technologies, Inc. 20241 SW Birch Street, Suite 201 Newport Beach, CA 92660 for helping us achieve excellent 360 degree photos.

Ethics approval and Consent to Participate. The data collection for the publication was completed via chart review and a case report format. Informed consent, obtained from all patients, for photographic consent was obtained in written form for all patients.

Consent for publication. All participants provided written consent for their use of photographs for presentation and publication. Patients are not identified by name in any photographs or text. Patients are aware that in some circumstances, the photographs may make their identity recognizable. In addition, patient identifying information has been removed from images and faces are omitted from photographs.

Availability of data and material: The chart and photographic review material are available from chart review from the office of Brian P. Dickinson, M.D., Inc.

Consent to participate. Photographic consent was obtained from the patients in the chart review for presentation and publication.

Authors' contributions: The manuscript work presented has not been published before and it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else. The publication has been approved by all co-authors, as well as by the institute where the work has been carried ou

There was no funding for the completion of the chart review or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest and no competing interests.

©2025 Le, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.