MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6383

Opinion Volume 14 Issue 2

1School of Public Health, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

2Department of Informatics and Computing, Faculty of Engineering, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana, Chile

3Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Universidad de los Andes, Chile

Correspondence: Francisco Mardones, School of Public Health, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Ave. Kennedy 3530, Department 1102,Vitacura, Santiago, Chile, Tel +569 62880070

Received: July 02, 2025 | Published: July 23, 2025

Citation: Mardones F, Caulier-Cisterna R, Donoso M. The demographic transition in Chile. MOJ Public Health. 2025;14(2):196-198. DOI: 10.15406/mojph.2025.14.00489

The demographic transition consists of the substitution of slow population growth, achieved with high fertility and mortality rates, for sustained slow growth with relatively low fertility and mortality rates. Most nations follow remarkably similar evolutionary trajectories in the last 70 years. A universal demographic transition toward population aging is evident. Chile has shown an outstanding health situation in Latin America mostly due to the delivery of strong health services that had favored mortality and fertility declines. Specific measures are presented. At the beginning of the 20th century, the infant mortality rate (IMR) was very high and did not improve; between 1924 and 1936 it remained stable hovering around 220. It declined in close association with the expansion of public primary health care between 1937 and 1950. Births whose deliveries were attended by professionals reached universal coverage in 1990, associated with the foundation of the National Health Service in 1952. IMR in year 2024 is 6.2. Family planning policy began in 1966 aiming to reduce the high maternal mortality figure. Fertility has declined considerably: the fecundity rate was 5.4 children per woman in 1960-65 while in 1990-1995 reached a figure of 2.1. Moreover, in 2024 it has fallen to 1.03 children per woman, representing one of the lowest rates in the world. The last public policy that has attempted to increase fertility was begun in 2011: it increased maternity leave from 12 to 24 weeks postpartum. It has been associated with an increase in the duration of breastfeeding but has not been associated with an increase in fertility. Instead, the decline of the total fertility rate and the incorporation of women to the workforce were associated and deserves new social policies. The Chilean population is aging and new proposals to confront this situation are needed.

Keywords: demographic transition, infant mortality, maternal mortality, fertility, aging, Chilean people

PAHO/WHO, pan American health organization/world health organization; IMR, Infant mortality rate

The demographic transition consists of the substitution of slow population growth, achieved with high fertility and mortality rates, for sustained slow growth with relatively low fertility and mortality rates.1

A study modeling age-specific population data from 200 countries over the past 70 years revealed that most nations follow remarkably similar evolutionary trajectories, differing primarily in the pace of change; a universal demographic transition toward population aging is evident, and even labor-abundant regions such as Africa, Asia, and South America are inevitably facing this demographic shift.2

The industrial revolution has been defined as the process of change from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing; these technological changes introduced novel ways of working and living and fundamentally transformed society.3 This process began in Britain in the second half of the 18th century and from there spread to other parts of the world.4

The industrial revolution led to greater availability of food and coal, and enabled to improve people's standard of living; the early decline in mortality and in fertility occurred before effective contraception became available.4 Scientific discoveries and medical advances did not significantly improve this.

In Latin America infant mortality started to decline in the first half of the twentieth century, while birth rates remained high but declined in the second half of the 20th century; that decline in infant mortality and fertility has occurred in relation to the discovery and widespread use of antibiotics and vaccines, along with advances in women's education and employment, with better access to medicine, contraceptives, and sanitation.5

Different measures that reduced mortality and fertility figures in Chile were delivered throughout the public health services, especially after the foundation of the National Health Service since 1952.6 Chile shows an outstanding health situation in Latin America mostly due to the delivery of strong health services.7,8 The aging of the population is increasing the demand for health services and the satisfaction with the system has declined.8

The demographic transition occurred in Chile

At the beginning of the 20th century, infant mortality in Chile was very high and did not improve. For example, between 1924 and 1936 it remained stable hovering around 220 infant deaths per one thousand live births.9

However, beginning in 1937, when the National Supplementary Feeding Program was launched, there was a significant increase in the coverage of the infant population served, and a clear decrease in infant mortality was recorded; the program was initiated by the Minister of Health, Eduardo Cruz-Coke and consisted of providing cow’s milk to children attending health checkups.10

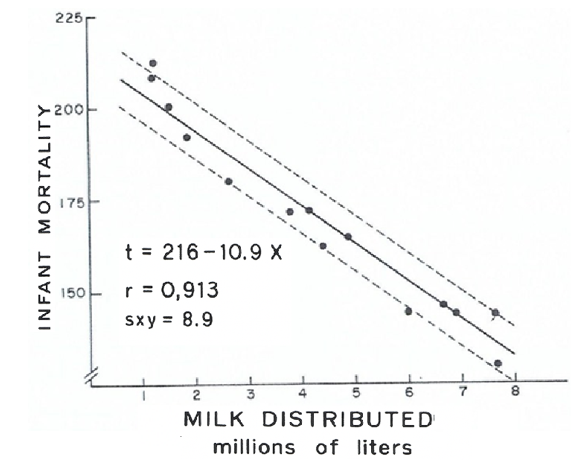

Figure 1 reveals that between 1937 and 1950 there was a high correlation between the decline in infant mortality and the distribution of artificial milk expressed in millions of liters.11 The high correlation demonstrated (r: -0.913) suggests that the milk distribution program and state medical services had focused on the infant population at greatest risk of malnutrition. Infant mortality declined from rates greater than 200 per thousand live births to rates close to 140 per thousand live births.

Figure 1 Correlation between the decrease in infant mortality and the distribution of milk by maternal and child health protection institutions.11

The infant mortality continued to decline in the next decades, primarily due to improved access to antibiotics and vaccines and a reduction in high fertility rates among the low-income population.12,13 In the 1950s, the infant mortality rate fluctuated around 130.2, in the 1960s around 108.8, in the 1970s around 63.4, and in the 1980s around 23.0.14 The decline continued, eventually reaching a rate of 6.2 deaths per thousand live births in 2024.15

Family planning policy in Chile began in 1966 aiming to reduce the high maternal mortality figure mainly due to induced abortion.16 Fertility in Chile has declined considerably: the fecundity rate was 5.4 children per woman in 1960-65 while in 1990-1995 reached a figure of 2.1.17 Moreover, in 2024 it has fallen to 1.03 children per woman, representing one of the lowest rates in the world.18 This figure, based on provisional data from the National Institute of Statistics, indicates a significant decrease compared to previous years and is well below the population replacement level, which stands at 2.1 children per woman.

Maternal mortality has dropped from a rate of 22.3 per 100,000 live births in 1997 to 11.6 in 2022.18 The number of maternal deaths decreased from 61 in 1997 to 22 in 2022. Chile lowered its maternal mortality rates thanks to successful public health policies that included; a) near-universal prenatal care and hospital delivery that has increased from a 90.5% coverage in 1980,19 to a 99.9% coverage nowadays;7,8,20–22 b) access to contraception through the Family planning program.12,13

Since 2017 there is legislation that decriminalizes abortion for three causes.23 The causes are: danger to the woman's life, fatal fetal nonviability and pregnancy resulting from rape. Ministry of Health records on the application of the law indicate that, in its seven years in force, law 21.030 has been invoked 5,370 times, and in 84.79% of cases, abortion was the option;23 this means that 4,553 abortions were performed. That figure divided by seven years would mean that around 650 abortions were performed per year. According to PAHO/WHO estimates, maternal mortality rates were 15 per 100 thousand live births in all years from 2017 to 2020, showing no variation.21 On the other hand, the Chilean Ministry of Health reported a decline from 17.3 in 2017 to 10.9 in 2019 followed by an increased figure of 21.9 in 2020 and a new decrease to 11.6 in 2022.18 According to the two sources, there was not a consistent association with the above quoted law implementation.23 Previous research has demonstrated that maternal mortality rates have been not related to the legal status of abortion.13

Otherwise, the overall mortality rate in Chile fell systematically from the beginning of the 20th century, going from an annual average of 30.4 deaths per thousand inhabitants for the decade 1910-19 to 5.3 per 1,000 inhabitants in the first decade of the 21st century;14 Chile's mortality rate was well below the world average (7.7 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2015) and slightly below the Latin American average (5.9 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2015). The age-adjusted overall mortality rate in 2019 was 4 per 1,000 inhabitants.21

Regarding the evolution of perinatal factors over a period of 20 years between 1996 and 2017, it can be appreciated that preterm births have increased.24 Live births have become more concentrated in the 35-year-old age group and older, where preterm births are more common; Live births in the under-20 age group have decreased significantly.22

On the other hand, the Chilean population is experiencing significant aging, according to the results of the 2024 Census, where the percentage of people aged 65 or over reached 14%, a considerable increase compared to 6.6% in 1992.25 At the same time, the percentage of people aged 14 or younger has decreased from 29.4% in 1992 to 17.7% in 2024. It has been concluded in different studies that as the aging of the population is increasing the demand for health services, the satisfaction with the system has declined showing inequities and deserving reform of the health system in Chile.8,26 Besides, the diagnosis of dementia in the older population is increasingly aggravating the demands on the health services.27

The demographic transition has been accompanied by the incorporation of women to the workforce that has also accelerated the fertility decline meaning that new social policies should help families to improve the fertility rates.28

Regarding the available support for working women to promote fertility rates, the Chilean Government passed a law in 2011 that increased maternity leave postpartum from 12 to 24 weeks for fully employed women.29 This measure was approved by all political sectors and has been associated with an increase in the duration of breastfeeding but has not been associated with an increase in the fertility of working mothers.

A recent review has pointed out possible effects and mechanisms of action of some of the most used contaminants—such as heavy metals (HMs), air pollutants and endocrine disruptors (EDs)—on female fertility; it also discusses the link between environmental pollution, climate and microbiome changes, because they can have surprising roles in reducing mammalian fertility.30

Chile is currently undergoing a demographic transition, with low fertility and mortality rates, accompanied with a growing population over 65. The current challenges are how to improve the fertility rate to avoid the problems faced by societies with an inverted population pyramid, a declining workforce, and a growing population requiring more healthcare. The actual experience of different countries regarding measures to avoid extreme fertility decline should be studied by policymakers. A recent study is an example of this sort: the analysis included a total of 61 studies focusing on pro-natalist policies, identifying cash benefit policies—such as payment at birth, allowances, paid maternity and paternal leave, childcare coverage, and tax exemptions—as the most influential.31

Project partially supported by: a) the Internal Competition for Funding of Research Assistants UTEM, 2025, code AI25-07, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana; b) the Regular Research Projects competition, 2023, code LPR23-17, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana; and c) Initiation project from Fondecyt 2025 Nr. 11250867.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2025 Mardones, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.