Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Review Article Volume 10 Issue 1

Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science, Clemson University, USA

Correspondence: Dr. Vincent S Gallicchio, Department of Biological Sciences, 122 Long Hall, College of Science, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA 29634

Received: July 10, 2025 | Published: August 11, 2025

Citation: Sharifi M, Gallicchio VS. Stem cell therapies in periodontal and dental regeneration: a comprehensive review. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):188-190. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00205

Recent advancements in stem cell biology have accelerated the development of stem cell-based therapies for periodontal tissue regeneration. Twenty-six human clinical studies performed across 10 countries have reported on the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for periodontal regeneration, making this approach one of the most thoroughly explored in oral and maxillofacial medicine. Among the various MSC types, dental stem cells (DSCs), including dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), and gingival MSCs (GMSCs), have shown advancements due to their accessibility, high proliferation rates, and strong osteogenic potential. Numerous studies have demonstrated the ability of these cells to reduce inflammation, enhance bone regeneration, and restore periodontal tissues. However, continued research and larger clinical trials are needed to fully understand their mechanisms and learn their potential.

Keywords: stem cell biology, periodontal tissue regeneration, oral and maxillofacial medicine, bone regeneration, clinical studies, regenerative dentistry

ADMPC, adipose tissue-derived multi-lineage progenitor cells; ADSC, adipose-derived stem cell; ALG-GEL, alginate-gelatin (hydrogel); BMAC, bone marrow aspirate concentrate; BM-MSC, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell; BMMSC, bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cell; DPSC, dental pulp stem cell; DPSC-EXO, dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes; DSC, dental stem cell; EXO, exosomes; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GMSC, gingival mesenchymal stem cell; hDPSC, human dental pulp stem cell; IL-6, interleukin 6; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PDL, periodontal ligament; PDLSC, periodontal ligament stem cell; PLSC, periodontal ligament stem cell (note: used interchangeably with PDLSC in some contexts); PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

The periodontium is composed of epithelial components and mesodermal-derived tissues such as alveolar bone, cementum, and the periodontal ligament (PDL).1 Periodontitis, a chronic inflammatory disease caused by dental plaque accumulation, affects nearly 90% of the global population and is a leading cause of tooth loss in adults.2 It is also associated with conditions such as atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.3 Traditional periodontal treatments such as mechanical plaque removal, guided tissue regeneration, enamel matrix derivatives, and bone grafting can slow disease progression and achieve partial regeneration, but their outcomes remain inconsistent, especially in severe cases.4

The discovery of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in 2000 opened new opportunities for regenerative therapies. Compared to bone marrow derived MSCs (BMMSCs), dental stem cells offer easier access, higher proliferation rates, and a greater potential for clinical use.5 This review summarizes current findings on the use of various stem cell types for periodontal regeneration and discusses their clinical applications, advantages, limitations, and potential for future therapies.

Among the various applications of stem cells for regenerating periodontal tissue, there are ways to inhibit bone loss before it becomes severe. DSCs have the potential for multipotent differentiation into osteogenic, chondrogenic, adipogenic, neurogenic, odontogenic, dentinogenic cells.5 Dental pulp stem cells are easily obtained, and have a high proliferation rate, lower cell senescence rate, and stronger osteogenic maintenance in comparison with periodontal ligament stem cells. Clinical trials have shown that transplantation of dental pulp stem cells into disinfected necrotic teeth has allowed for the recovery of tooth vitality and vertical and horizontal root growth in immature teeth.6 Findings show that exosomes derived from hDPSC aggregates mediate the tooth regeneration process by activating tooth developmental gene expression and guiding the cell fate of hDPSCs.7 One study explores how dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes (DPSC-EXO) can reduce periodontitis and promote periodontal tissue regeneration. Findings of this study show that DPSC-EXO inhibits the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, which has an anti-inflammatory effect. The experimentation was performed in rats, where results indicate that there were fewer osteoclasts in periodontal tissue in the DPSC-EXO group than in the PBS group. Osteoclasts reabsorb bone, and excessive activity of osteoclasts can disrupt the balance of reabsorption and new bone formation.2

Gingival tissue derived MSCs (GMSCs) exhibit proliferative characteristics and secrete high amounts of exosomes that suppress inflammatory bone loss. GMSC-secreted exosomes were shown to reduce bone reabsorption in mice, indicating smaller amounts of osteoclasts in comparison with a control group. GMSC treatment downregulates Wnt pathways, which are involved in inflammatory disorders such as sepsis, Alzheimer’s disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Specifically, Wnt5a expression in the gingival tissue is associated with periodontal inflammation and can be controlled by GMSC exosome therapy.3 Another study that reinforces the claims discussed uses Sclerostin, which is a protein that antagonizes the effects of the Wnt pathway, influencing bone homeostasis.1

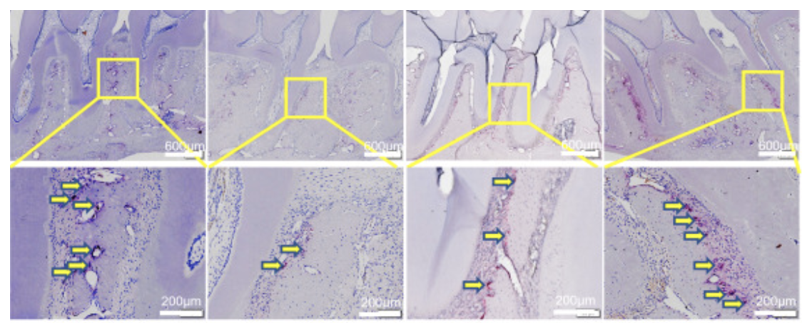

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) may be isolated from different sources, which include bone marrow, blood from the umbilical cord, adipose tissue, pancreas, liver, skeletal muscle, dermis, and the synovial membrane.8 A study done by the Molecular Laboratory for Gene Therapy & Tooth Regeneration compared the regenerative properties of different types of MSCs. Results concluded that DPSCs Maintain Higher Proliferation and Osteogenesis Capability Compared to PDLSCs, ADSCs, and BMMSCs.9 Recently (MSC)-like cells have been discovered in the periodontal ligament (PDLSCs).10 There has been extensive research done to investigate the use of Periodontal Ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) for potential periodontal regeneration, and the findings conclude major success. MSCs show multi-differentiation capability and self-renewability in vitro. To detect the recruitment of MSCs to the site of injury, a study was performed where alveolar bone of mandibular first molars was removed in mice (Figure 1).

Figure 1 PBS, EXO, and health, PD comparison of osteoclast quantity (stained red) between first and second molars.2

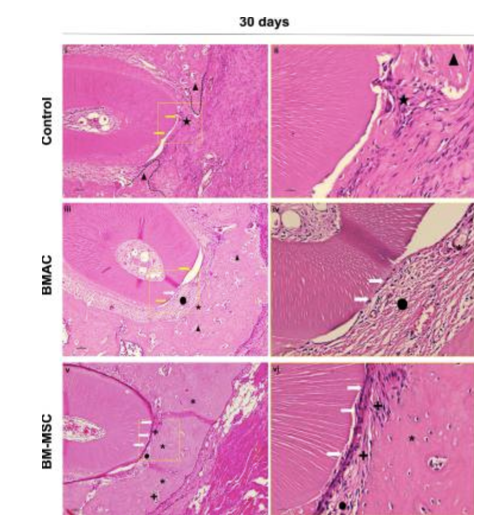

Figure 2 demonstrates that MSCs are involved in healthy, constant regeneration of periodontal tissue.11 A study conducted by the Health Research Institute of Santiago (IDIS) evaluated three groups to determine the efficacy of MSC in periodontal regeneration. Group 1: MSCs alone or mixed with regenerative materials. Group 2: only regenerative materials. Group 3: no regenerative material nor MSCs. Results concluded that group 1 had far more regenerative properties than group 2 or group 3.8 Bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) is a source of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, but MSCs only represent a fraction of the implanted cells. The goal of a specific study was to compare the effects of BMAC and BM-MSCs and evaluate the amount of periodontal regeneration performed by each of them. In 15 days, some specimens treated with BM-MSCs showed defects closed with new bone and a new periodontal ligament containing parallel fibers under the dental root. In 30 days, all defects filled with BMAC or BM-MSCs showed the same results that some BM-MSCs had within 15 days. Regular and mature bone was observed at 30 days in both treatment groups, but more frequently in those treated with BM-MSCs. Unlike specimens treated with BMAC, all specimens filled with the BM-MSCs showed new cementum formation in the distal root of the first molar, and two specimens had 100% of the root covered with new cementum. Complete periodontal regeneration was achieved only in the BM-MSC group.

Figure 2 FACS analysis showed that the percentage of MSCs in bone marrow of mice with periodontal defects was significantly lower than in controls.11

Although using BMAC is less expensive, data from this experiment showed that it induces bone, but not cementum formation. In contrast, BM-MSCs cause cementum formation, faster bone formation and maturation, and successful periodontal ligament regeneration.12

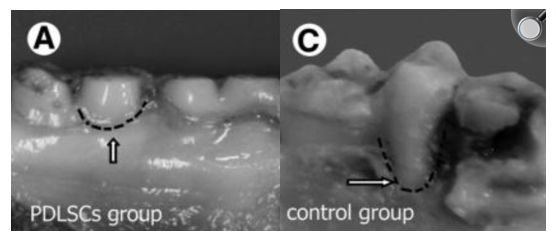

Periodontal ligament stem cells (PLSCs) are known for their regenerative ability. They are easy to access and have abundant tissue availability, so they are ideal to use for tissue engineering. The use of exosomes can have the same effects of their source cells, without the immune response or risk of tumor formation. Several studies have shown that the effects of MSCs are mainly through paracrine mechanisms. The exosome is considered to be a paracrine factor in MSCs that could potentially be effective in regeneration of tissues. In a study performed on rats with alveolar bone defects, exosomes were isolated from PDLSCs extracted from humans, and they were combined with the ALG-GEL hydrogel to assess regeneration ability. Results show that bone treated with hydrogel plus the exosome have higher regenerative properties than the control group and bone treated with only hydrogel.13 A study performed on miniature pigs included the removal of bone and ligaments around the first molars to test the treatment potential of PDLSCs (Figure 3). After implantation of PDLSCs, results indicated that periodontal regeneration was improved significantly in comparison with the control group. The height of periodontal alveolar bone was restored to almost the original height.4

Figure 3 Histological view of the center of the periodontal fenestration defect within postoperative 30 days of spontaneous healing.12

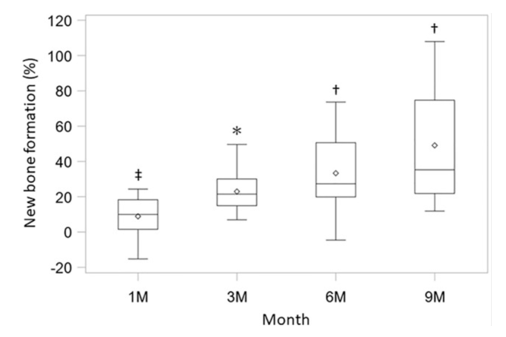

In Figure 4, it is shown that the bone regenerated with the use of PDLSCs was greater than that of the control group. A study that evaluated the safety and efficacy of adipose tissue-derived multi-lineage progenitor cells (ADMPC), implanted the cells into bone defects of 12 periodontitis patients. ADMPCs show great differentiation ability and the trophic factors secreted from them stimulated the differentiation of periodontal ligament cells, something that is critical for tissue regeneration (Figure 5).14

Figure 4 Bone growth comparison between PDLSCs group and control group.4

Figure 5 Clinical assessment of new bone formation. The new bone formation rate was measured using X-ray images at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months (n = 12).

*p <0.0001, †p <0.001, ‡p <0.025, with the use of a one-sample t-test based on the closed testing procedure.14

The bone regeneration after 36 weeks was shown to be related to ADMPCs. Subjects in the current study included those with more severe periodontal tissue defects, which indicates that the efficacy observed after ADMPC transplantation was clinically significant.14 Most published clinical studies in humans show that the use of DSCs is associated with successful bone regeneration with no reported side effects.15,16

While stem cell-based therapies for periodontal regeneration show great promise, several challenges remain before they can become widely adopted in clinical practice. Safety concerns, such as the potential for tumor formation due to the non-directional differentiation must continue to be addressed, although clinical studies using dental stem cells (DSCs) have so far reported no adverse effects.5 Among the cell types explored, dental MSCs including DPSCs, PDLSCs, and GMSCs, are particularly attractive due to their regenerative potential and ability to be extracted easily. Other MSC sources such as BMMSCs, ADSCs, ADMPCs, and BMAC are also rising in popularity, though their effectiveness is still being explored. Future research should focus on expanding clinical trials, learning more about the mechanisms of differentiation, and deepening the understanding of cell capabilities. After important research, these therapies have the potential to accelerate treatment for periodontitis and other dental conditions.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Sharifi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.