Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Review Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Department of Biotechnology, Haldia Institute of Technology, India

2Institute of Child Health, India

Correspondence: Pranab Roy, Institute of Child Health, Kolkata, 700017, India

Received: October 10, 2025 | Published: October 30, 2025

Citation: Mitra S, Bose S, Basu S, et al. Novel advances in lentiviral gene therapy for sickle cell anemia. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):239‒247. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00211

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is a severe monogenic blood disorder caused by a single point mutation in the β-globin gene, leading to the production of abnormal hemoglobin S and subsequent erythrocyte deformation, chronic hemolysis, and vaso-occlusive crises. Conventional therapies, such as hydroxyurea and blood transfusions, offer symptomatic relief but do not address the underlying genetic defect. Lentiviral gene therapy has emerged as a promising curative strategy, enabling the stable integration of functional β-globin or anti-sickling globin variants into autologous hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to restore normal hemoglobin production. Recent advances in vector engineering, promoter optimization, transduction efficiency, and stem cell culture protocols have significantly improved the efficacy and safety profile of this approach. Clinical trials have demonstrated sustained therapeutic hemoglobin expression, reduction in disease complications, and improved quality of life for treated patients. However, critical challenges remain, including high treatment costs, the need for myeloablative conditioning, and limited accessibility in low-resource settings. This review discusses the latest innovations in lentiviral vector technology, preclinical and clinical outcomes, existing limitations, and future directions aimed at broadening the global applicability of this curative therapy.

Keywords: sickle cell anemia, lentiviral vector, gene therapy, β-globin; hematopoietic stem cells, fetal hemoglobin

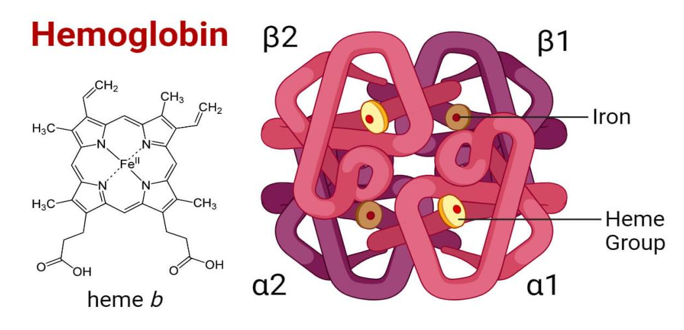

Haemoglobin (molecular weight of 65450) is an oligomeric, allosteric , conjugated protein with four polypeptide chains joined by covalent and Hydrogen bonds. It contains heme prosthetic group , which is an iron containing porphyrin derivative (Figure 1).1

Figure 1 Diagram of structure of haemoglobin molecule74

Based on the nature of globin proteins, a variety of hemoglobin molecules are produced in humans. All are tetramers consisting of different combination of globin polypeptide chain each encoded by a separate gene.1

Hemoglobin A(HbA): The most prevalent human hemoglobin tetramer, hemoglobin A (HbA), commonly referred to as adult hemoglobin, hemoglobin A1, or α2β2, makes up more than 97% of the total hemoglobin in red blood cells.2

Hemoglobin A2(HbA2): Normal human blood contains low amounts of hemoglobin A2 (HbA2), a normal variant of hemoglobin A that is made up of two alpha and two delta chains (α2δ2). People with beta thalassemia or those who are heterozygous for the beta thalassemia gene may have elevated hemoglobin A2. All adult individuals have tiny amounts of HbA2 (1.5–3.1% of all hemoglobin molecules), and sickle-cell disease patients have roughly normal levels of this protein.3

Hemoglobin F(HbF): The primary oxygen-carrying protein in the human fetus is called fetal hemoglobin, or foetal hemoglobin (also known as hemoglobin F, HbF, or α2γ2). Fetal red blood cells contain hemoglobin F, which helps carry oxygen from the mother's bloodstream to the fetus's organs and tissues. Around six weeks into the pregnancy, it is produced, and levels stay high until the baby is about two to four months old.4

Hemoglobin C (HbC): is a structural hemoglobin variation resulting from a single-point mutation in the β-globin gene at codon 6 (GAG→AAG), replacing glutamic acid with lysine. This amino acid shift decreases hemoglobin solubility, encouraging intracellular crystal formation and mild red cell stiffness, resulting in mild chronic hemolysis. Peripheral smears often reveal target cells and HbC crystals. Homozygous HbCC usually manifests as mild anemia, splenomegaly, and sometimes jaundice, whereas heterozygotes (HbAC) are clinically asymptomatic. The compound heterozygous status with HbS (HbSC disease) causes a milder type of sickle cell disease.

Hemoglobin E(HbE): is caused by a β-globin gene mutation at codon 26 (GAG→AAG), which replaces glutamic acid with lysine and creates an aberrant splicing site that inhibits β-globin synthesis. This causes a modest structural abnormality in conjunction with a thalassemia-like phenotype, resulting in microcytosis, hypochromia, and target cells on peripheral smear. Homozygous HbEE typically causes mild anemia or no symptoms, whereas heterozygotes (HbAE) are asymptomatic but have microcytosis. The clinically important variant arises when HbE is inherited with β-thalassemia (HbE/β-thalassemia), with severity ranging from thalassemia intermedia to transfusion-dependent anaemia.

Hemoglobin S (HbS): is the most frequent pathogenic hemoglobin variation, caused by a point mutation in the β-globin gene at codon 6 (GAG→GTG), which replaces glutamic acid with valine. This hydrophobic alteration facilitates intermolecular polymerization of deoxygenated hemoglobin, resulting in red blood cell deformation into the distinctive sickle shape. Sickled cells exhibit greater stiffness, membrane damage, and a shorter lifespan, resulting in persistent hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusion, and multi-organ consequences. Homozygous HbSS causes sickle cell disease, whereas heterozygotes (HbAS) are typically asymptomatic but can develop symptoms in extreme hypoxic conditions. HbS is extremely common in sub-Saharan Africa, portions of the Middle East, and India, and its distribution is connected to a selective advantage against severe malaria.

A collection of hereditary blood illnesses linked to hemoglobin is known as sickle cell disease (SCD). Sickle cell anemia is the most prevalent kind. A defect in the oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin, which is present in red blood cells, is the result of sickle cell anemia.5 In some cases, this causes the red blood cells to take on an odd sickle-like shape, which prevents them from deforming as they go through capillaries and results in blockages.6 Usually, sickle cell disease symptoms start to appear between the ages of five and six months.5

Numerous health issues could arise, including joint pain episodes (sometimes called sickle cell crisis), anemia, hand and foot edema, bacterial infections, lightheadedness, and stroke.5,7 As people age, they are more likely to experience severe symptoms, such as chronic pain.5 The typical life expectancy for individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) is between 58 and 66 years, but they seldom reach adulthood without therapy.8,9 Sickle cell disease affects all of the major organs. The sickle cells' aberrant functions and incapacity to efficiently pass through the tiny blood vessels can harm the liver, heart, kidneys, gallbladder, eyes, bones, and joints.10

When a person inherits two faulty copies of the β-globin gene, which produces hemoglobin, one from each parent, sickle cell disease results.11 Depending on the precise mutation in each hemoglobin gene, there are a number of subtypes.6 Variations in temperature, stress, dehydration, and elevation can trigger an attack.5 Sickle cell trait is the term used to describe a person who has a single aberrant copy but often shows no symptoms.6 These individuals are also known as carriers (Table 1).11

|

Developmental stages |

Types of globin proteins |

Types of hemoglobin |

|

Embryonic (< 8 weeks) |

ξ2ε2 |

Gower 1 |

|

Fetal (3-9 months) |

α2 γ2 |

HbF |

|

Adult (from birth) |

α2ß2 α2δ2 |

HbA1 HbA2 |

Table 1 Different Hb expressed during different developmental stages of humans1

In deoxygenated environment, HbS undergoes polymerization, resulting in sickling of red blood cells (RBCs), ongoing hemolysis, vaso-occlusion, and damage to multiple organs. A crucial internal modulator of disease severity is fetal hemoglobin (HbF, α₂γ₂), which is naturally produced in the fetus and generally decreased after birth. Increased HbF levels have been demonstrated to improve the clinical symptoms of SCA via several molecular and physiological processes.12

Molecular Mechanism of HbF Protection: HbF is structurally different from adult hemoglobin(HbA, α2β2) because it has two γ- globin chains in place of β- globin. Significantly, γ- globin chains are not involved in the creation of polymeric HbS. Consequently, HbF disrupts the conformation and expansion of HbS polymers.13

When HbF is integrated into erythrocytes particularly when found at adequate levels within single cells it functions in a dominant-negative manner, preventing sickling during hypoxic circumstances. 14

Clinical Evidence Supporting the Advantages of HbF: Numerous epidemiological and clinical studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between HbF levels and disease severity in patients with SCA. People with hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH), a condition where γ-globin gene expression persists into adulthood, frequently display mild or asymptomatic variants of SCA even while possessing the HbS mutation.15

HbF levels >20% were associated with significantly lower hospitalization rates, fewer acute chest syndrome episodes, and increased survival in major cohort studies, including the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease (CSSCD). These results lend credence to the idea that a key tactic in disease-modifying treatments for SCA is therapeutic targeting of HbF.16

Higher HbF levels are associated with reduced incidence and severity of:

Vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs)

Stroke and silent cerebral infarcts

Acute chest syndrome (ACS)

Hemolysis-related complications such as leg ulcers and priapism

Chronic organ damage, including nephropathy and retinopathy.9

These multifactorial benefits underline HbF not just as a molecular target but as a comprehensive therapeutic modifier.17

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an inherited hemoglobinopathy caused by a single nucleotide substitution in the β-globin gene, leading to the production of sickle hemoglobin (HbS).18 Under hypoxic conditions, HbS polymerizes, resulting in red blood cell deformation, hemolysis, and recurrent vaso-occlusive events.19 One effective therapeutic strategy is the induction of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which inhibits HbS polymerization by forming stable α₂γ₂ tetramers that reduce sickling.20 Pharmacological HbF induction seeks to reactivate γ-globin gene expression, which is normally silenced after birth, thereby increasing HbF levels and mitigating disease severity.21 Agents such as hydroxyurea, decitabine, and histone deacetylase inhibitors have demonstrated the ability to elevate HbF by modulating transcriptional and epigenetic regulators.22 This approach remains a cornerstone in SCA management, offering a cost-effective option suitable for both high- and low-resource healthcare settings.23

Hemoglobin S Polymerization Inhibition: Increasing fetal hemoglobin (HbF) prevents red cell sickling and improves red blood cell survival by interfering with hemoglobin S (HbS) polymerization, which is the main advantage of hydroxyurea (HU) in sickle cell anemia (SCA).24

Erythroid Progenitor and Precursor Cell Activity: Hydroxyurea promotes the growth of early erythroid progenitors that support the development of γ-globin, which in turn enhances the generation of HbF.25 In late-stage erythroid precursors already dedicated to hemoglobin synthesis, this directly increases γ-globin transcription.26 HU selectively upregulates Gγ-globin mRNA and raises the total hemoglobin content in K562 erythroleukemia cells.27 In two-phase cultures made from normal peripheral blood, it likewise increases HbF and γ-globin mRNA,but has less of an impact on β-globin.28

The Nitric Oxide (NO)-Mediated Route: Both in vitro and in vivo, hydroxyurea is broken down to yield nitric oxide (NO).29 Protein kinase G (PKG) is activated by NO through the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), which raises cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels. In erythroid cells, this signaling cascade results in increased expression of the γ-globin gene.30 Furthermore, NO has the ability to deactivate the tyrosyl radical on ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), an essential enzyme for DNA synthesis, which may have an impact on erythroid cell cycle and encourage the synthesis of HbF.22

Interaction with Butyrate and Hemin Route: Hydroxyurea and other HbF inducers, such as butyrate and hemin, have a similar route. Inhibiting either sGC or PKG eliminates the HbF-inducing actions of these drugs, indicating a mutual reliance on the NO–sGC–cGMP axis.30

Some other methods

Dna methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., Decitabine, Azacitidine)

Mechanism of Action: DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors like decitabine and azacitidine function by inhibiting DNMT1, which maintains methylation at the γ-globin gene promoter. Hypomethylation of this promoter region leads to reactivation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production in adult erythroid cells, counteracting the effects of sickle hemoglobin (HbS).

Clinical Evidence: Low-dose decitabine has shown promise in clinical studies. When combined with tetrahydrouridine (THU) to enhance oral bioavailability, decitabine can induce sustained and clinically significant increases in HbF without causing severe cytotoxicity. A randomized phase 1 trial confirmed that oral decitabine plus THU raised HbF levels while maintaining safety in patients with sickle cell anemia and β-thalassemia.31

An earlier study also demonstrated that decitabine, even as a monotherapy, was effective in increasing HbF and improving hematologic parameters, showing a consistent and durable effect.30

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (e.g., Butyrate, Vorinostat)

Mechanism of Action: HDAC inhibitors promote histone hyperacetylation, leading to chromatin relaxation and enhanced transcription of the γ-globin gene. This results in increased HbF synthesis. Among these, sodium butyrate and vorinostat (SAHA) have been studied most extensively.31

Clinical Evidence: Sodium butyrate was one of the earliest agents found to stimulate HbF production. Clinical studies showed that it could induce γ-globin expression in patients with sickle cell anemia, although the effect was often transient and required continuous infusion.32 More recently, vorinostat and other HDAC1/2 inhibitors have demonstrated HbF-inducing effects in vitro, acting via chromatin remodeling mechanisms.33

Despite their potential, HDAC inhibitors have not yet been approved clinically for sickle cell disease due to challenges like short duration of action, toxicity, and delivery route limitations.

The most promising treatment for sickle cell anemia (SCA) is gene therapy, which targets the disease's basic cause rather than its symptoms. Gene therapy offers long-lasting and possibly permanent benefits by correcting the underlying genetic mutation or its effects, in contrast to conventional medicines like hydroxyurea or transfusions.

Advantages over conventional therapies :

Although several conventional therapies have improved the quality of life and prognosis of individuals with sickle cell anemia (SCA), they largely function as palliative or disease-modifying strategies rather than curative interventions. Gene therapy, by contrast, offers a targeted, potentially curative, and individualized solution.

Constraints of Hydroxyurea: Hydroxyurea is presently the most commonly utilized disease-modifying medication for SCA. Its main action is the stimulation of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which disrupts the polymerization of hemoglobin S (HbS), thus decreasing red cell sickling and related complications.34

Its efficacy varies among the patient population:

10–20% of patients do not respond adequately, and even those who do respond may have HbF levels that are too low to avert organ damage.35

It demands continuous compliance, and skipped doses lower its effectiveness.

Worries persist about prolonged use, particularly in children and during pregnancy, because of possible cytotoxic effects and influence on fertility.34

Consequently, although hydroxyurea is a vital treatment, it does not eradicate disease pathology, and for numerous patients, it is inadequate as a sole therapy.

Challenges with Chronic Blood Transfusions: Blood transfusion therapy is a common method to treat anemia and avert stroke in children with SCA.36 Nonetheless, ongoing transfusions carry significant risks, such as:

Iron overload: Necessitates lifelong chelation treatment to avert damage to the liver, heart, and endocrine system.37

Alloimmunization: Because of antigenic variances between the blood of the donor and recipient, this can lead to delayed hemolytic reactions and restrict future transfusion choices.38

Transmission of infectious diseases: While currently uncommon, it is still a worry in areas lacking proper blood testing.

Logistical challenge: Necessitates regular hospital trips, rendering it unfeasible in resource-constrained environments.

These issues diminish the long-term effectiveness of transfusions as a chronic management option, particularly in low- and middle-income nations.

Targeting the genetic cause of disease:

The β-globin gene (HBB) undergoes a single nucleotide substitution (Glu6Val) in SCA, resulting in hemoglobin S (HbS), which polymerizes upon deoxygenation and sets off a series of pathological consequences, such as hemolysis, vaso-occlusion, and damage to multiple organs.35

Three primary approaches are provided by gene therapy:

Using lentiviral vectors, anti-sickling β-globin genes are added.

Gene correction with base editors or CRISPR/Cas9

Disruption of BCL11A or other repressors to reactivate HbF.39

These methods restore normal erythropoiesis by correcting illness at the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) level.

The ability of lentiviruses, a genus of retroviruses, to infect both dividing and non-dividing cells and integrate their genetic material into the host genome for transgene expression over an extended period of time, is one of their defining characteristics. Since it takes a long time for symptoms to appear in natural hosts after infection, their name is derived from the Latin lentus, which means "slow." According to their structural makeup, lentiviruses are enveloped viruses with a genome made of single-stranded RNA that undergoes reverse transcription into DNA throughout the course of infection. In gene therapy, virulence genes are removed from modified lentiviral vectors to make them replication-deficient, while components necessary for transgene delivery and stable integration are retained.40

Lentivral vectors are utilized to transfer therapeutic β-globin genes or gene-editing components to the patient's autologous hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in sickle cell anemia (SCA). The objective is to either revive the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) through targeted gene alteration or introduce an anti-sickling β-globin variant. Lentiviruses' capacity for integration guarantees that the therapeutic gene is expressed continuously in every offspring of the transduced HSPCs, possibly offering a permanent treatment.41

Lentiviral vectors are preferred over other viral delivery systems, such as γ-retroviruses, for several reasons:

High transduction efficiency.

Lower genotoxicity risk due to integration patterns favoring transcriptionally active but less oncogene-prone genomic regions.

Stable, long-term expression of the therapeutic gene, avoiding repeated administrations.

Larger transgene capacity (~8–10 kb) suitable for complex gene cassettes.

Patients with SCA treated with autologous HSPCs transduced with lentiviral β-globin vectors achieve transfusion independence and significantly lower hemolysis markers, according to several clinical trials, including LentiGlobin BB305 (Bluebird Bio).42 The potential of lentiviral-based gene therapy as a treatment approach for SCA is highlighted by these findings, especially for patients who do not have appropriate donors for allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

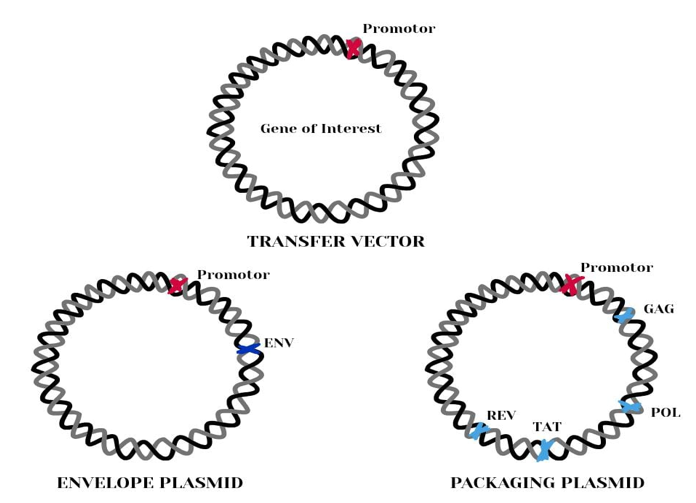

Lentiviral packaging plasmids are essential molecular tools used to produce replication-deficient lentiviral particles for gene delivery. In modern gene therapy, they are a preferred vector system because they can efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, integrate into the host genome, and provide long-term expression of the transgene.43,44 The biosafety of these systems is achieved by splitting the viral genome into separate plasmids so that no single plasmid contains all the genetic material needed to produce a replication-competent virus.45,46

These plasmids can be divided into three main categories:

Transfer vectors: carry the therapeutic or experimental gene of interest (GOI)

Packaging plasmids: provide viral structural proteins and enzymes

Envelope plasmids: determine viral host range (tropism)45,47

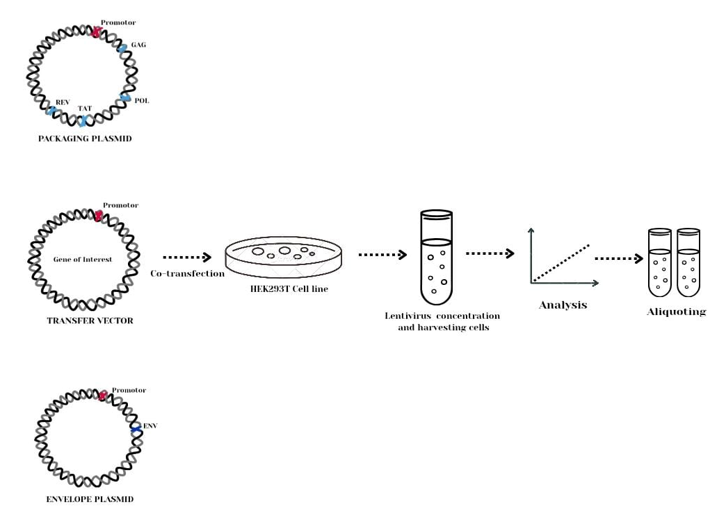

When these three plasmids are co-transfected into a suitable packaging cell line (such as HEK293T cells), the proteins and RNA assemble into infectious viral particles, which are secreted into the culture medium and later used to transduce target cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Three categories of plasmids used in lentivirus production for treatment of sickle cell anemia53

Transfer vector (Expression vector)

The transfer vector is the backbone that carries the gene of interest under the control of a chosen promoter (e.g., CMV, EF1α, PGK), allowing targeted expression in the transduced cells.47

It contains:

5′ and 3′ Long Terminal Repeats (LTRs) recognition sites for reverse transcription and integration

Packaging signal (Ψ) directs the RNA genome into the assembling virus

Regulatory elements like WPRE (woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element) to boost expression.48

In self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vectors, the U3 region of the 3′ LTR is deleted to prevent unwanted activation of host genes, increasing safety.46

Packaging plasmids (Helper plasmids)

These plasmids supply the structural and enzymatic proteins required for assembling the viral capsid and performing the replication steps, but without packaging their own coding sequences, thus avoiding the formation of replication-competent virus.43,48

Gag/Pol

Rev

Rev is a regulatory protein that binds to the Rev Response Element (RRE) in viral RNA, enabling the nuclear export of unspliced and partially spliced RNA.48 Without Rev, these RNA molecules remain in the nucleus, and the structural proteins they encode are not translated, severely reducing viral production.

Tat

Tat enhances transcription from the HIV-1 LTR by recruiting transcription elongation factors to the viral promoter. In third-generation packaging systems, Tat is often unnecessary because heterologous promoters drive gene expression in the transfer vector, improving biosafety.43

The envelope plasmid encodes the viral glycoprotein responsible for binding to receptors on target cells and mediating viral entry. The most common is VSV-G (vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein), which confers broad tropism, allowing the vector to infect many mammalian and non-mammalian cell types.49 VSV-G is also highly stable, allowing lentiviral particles to withstand ultracentrifugation and storage at −80°C without losing infectivity.50,51

Other envelopes can be used to alter tropism or improve transduction efficiency in specific tissues a process known as pseudotyping.( Figure 3)52

Figure 3 The use of multiple plasmids allows for better control over the packaging process and helps avoid recombination events that could result in replication-competent lentiviruses. The above diagram illustrates the lentivirus packaging process at bioinnovatise where our team uses hek293t cells for lentivirus packaging.53

Step 1: Patient’s Stem Cell Collection (HSPCs)

Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) are collected from the patient’s bone marrow or blood.54

These cells can give rise to all types of blood cells including red blood cells.55

Step 2: Engineering the lentiviral vector

The lentiviral vector is loaded with:

The βAS-3 gene, a modified β-globin gene with three changes (G16D, E22A , T87Q) to prevent sickling.56

The changes are as follows:

An artificial microRNA(miRNA) – a molecule that silences the sickle gene (βs-globin) or repressor gene (like BCL11A) that block fetal hemoglobin production.57

These components are under control of erythroid-specific promoters, so they are only active in red blood cell development.( Table 2)58

|

Mutations |

Original amino acid |

Changed to |

Position |

Purpose |

|

G16D

|

Glycine(G) |

Aspartic Acid(D) |

16 |

Improves interaction with α-globin, so that βAS-3 out competes βs genes. |

|

E22A |

Glutamic Acid(E) |

Alanine(A) |

22 |

Blocks axial contacts that keep HbS molecule stick together. |

|

TB7Q |

Threonine(T) |

Glutamine(Q) |

87 |

Prevents lateral polymer contacts disrupting the polymerisation of HbS. |

Table 2 β-globin gene with three changes

Step 3: Transducing the Patient’s HSPCs

The patient’s stem cells are exposed to the lentiviral vector in the lab.59

The virus enters the stem cells and delivers the new βAS-3gene and the miRNA into the cell’s genome.[56]

These genetically modified HSPCs now carry the instructions to make the healthy hemoglobin.59

Step 4: Preparing the Patient

The patient undergoes mild chemotherapy to reduce the number of blood forming Hematopoietic Stem Cells.60

It is called mild or non-myeloablative because

Does not destroy bone marrow cells.

Less toxic than high dose regimens used in cancer.

Causes fewer side effects and has faster recovery

The most commonly used drug is Busulfan60

A chemotherapy agent that selectively depletes Hematopoietic Stem Cells.

Carefully given in controlled doses.

Goal is to make enough room for the modified stem cells to engraft, without completely wiping out the patient’s immune system.

This step is important because, without this step61

The patient’s original stem cells would outcompete the modified ones.

The gene therapy would be ineffective because too few modified cells would engraft.

Step 5: Infusion of Modified HSPCs

The patient receives the modified HSPCs back via infusion like a blood transfusion.

These cells settle in the bone marrow, start dividing and make new cells.62

Step 6: Expression of Therapeutic Gene

The new blood cell made from these stem cells:

Produce anti-sickling hemoglobin(HbAS3)

Have reduced levels of sickle hemoglobin(HbS)

Have increased fetal hemoglobin(HbF) if BCLL1A was silenced.56

Patient's Background and Clinical History: The patient, a 13-year-old male, was diagnosed with homozygous sickle cell anemia (HbSS genotype). A point mutation in the β-globin gene (HBB) resulted to a Glu6Val substitution. Despite optimal conventional care, the patient developed an aggressive clinical phenotype with recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (VOC), chronic anemia, and progressive end-organ problems.

A detailed clinical history indicated:

Onset of VOC at early childhood (first episode at 3 years of age)

Frequent hospitalizations (6–8 per year) for pain crises

Multiple transfusions, leading to secondary iron overload (serum ferritin >3000 ng/mL)

Evidence of early splenic dysfunction on ultrasonography

Pulmonary hypertension and reduced exercise tolerance (6-minute walk test <400 m)

Despite adherence to hydroxyurea therapy at maximum tolerated doses, the patient continued to experience significant morbidity. The decision to pursue gene therapy was based on failure of standard treatments, lack of matched sibling donors for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and progressive disease burden.54,59

Pre-treatment evaluation

A comprehensive pre-treatment workup included:

Hematological assessment: Hemoglobin 7.5 g/dL, reticulocyte count elevated, high LDH indicating hemolysis.

Iron studies: Elevated ferritin, liver MRI confirming iron overload.

Organ function evaluation: Echocardiography, pulmonary function tests, and MRI of the brain to exclude silent strokes.

Bone marrow aspiration: Adequate hematopoietic reserve confirmed.

Psychosocial assessment: Multidisciplinary counseling to ensure understanding of risks and long-term follow-up requirements.59

Therapeutic strategy

The chosen approach was ex vivo lentiviral gene therapy, using the patient's own CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that were modified with a self-inactivating lentiviral vector encoding βA-T87Q, an anti-sickling form of β-globin.

Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and collection: Due to the risk of vaso-occlusion with G-CSF in sickle cell disease (SCD), plerixafor was used alone for stem cell mobilization. Leukapheresis produced enough CD34+ cells for transduction, resulting in high viability, greater than 90%.

Ex vivo lentiviral transduction: The vector used had: - Erythroid-specific promoter elements from the β-globin locus control region (LCR) - Codon-optimized βA-T87Q sequence - Self-inactivating long terminal repeats (SIN-LTRs) to reduce the risk of insertional mutagenesis The transduction achieved a vector copy number (VCN) of 2.8 per genome in the final cell product, exceeding the target threshold for clinical effectiveness.

Myeloablative conditioning: Before reinfusion, the patient underwent busulfan-based myeloablation. Pharmacokinetic monitoring ensured optimal exposure while reducing toxicity.

Cell infusion: The modified autologous HSPCs were cryopreserved, thawed, and infused into the patient through an intravenous line. The procedure was well tolerated and did not cause immediate infusion-related reactions.57

Post-treatment monitoring and clinical outcomes

Hematologic recovery

Neutrophil engraftment: Day +20 post-infusion

Platelet recovery: Day +28

Transfusion independence achieved by 3 months post-treatment

Hemoglobin expression profile

By 6 months:

Total hemoglobin: 11.2 g/dL

HbA-T87Q made up 45% of total hemoglobin

HbS proportion decreased to less than 50%

High HbF levels (greater than 20%) remained, supporting the anti-sickling effect.59

Reduction in VOC frequency

The patient reported no VOC episodes in the first year after therapy, down from a pre-treatment average of more than 6 per year.

Organ function improvement

Improved exercise tolerance (6-minute walk test: 520 m)

Normalization of tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity on echocardiography

Stabilization of splenic size and function.59

Long-Term Follow-Up and Molecular Analysis:

Longitudinal monitoring confirmed:

Stable vector copy number in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Persistent expression of HbA-T87Q with minimal decline over time.

Polyclonal hematopoiesis without abnormal clonal expansion.

Despite encouraging clinical outcomes, the application of lentiviral gene therapy in Sickle cell anemia disease treatment faces a range of biological, technical, logistical, and ethical challenges that limit its widespread adoption.

Efficient stem cell harvest and quality control: The therapeutic success of lentiviral gene therapy is dependent on the availability of a sufficient number of high-quality autologous HSPCs capable of long-term engraftment. Chronic inflammation, repeated vaso-occlusive events, and bone marrow stress are frequently associated with impaired stem cell mobilization and function in SCD patients.63 The conventional mobilization technique including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is not recommended due to the potential of causing severe vaso-occlusive crises (VOEs) and splenic rupture.64 Alternative regimens, such as plerixafor alone or in combination with low-dose chemotherapy, have shown varying efficiency.65 Suboptimal HSPC yields may limit vector transduction efficiency and therapeutic benefit.

Vector manufacturing and transduction efficiency: Lentiviral vector manufacture is difficult, expensive, and time-consuming, necessitating GMP-compliant facilities. Large-scale manufacturing remains a hurdle, particularly considering the high vector dosages required for successful HSPC transduction in SCD.66 Furthermore, cell-intrinsic variables such as HSPC proliferation and oxidative stress in SCD bone marrow microenvironments can influence lentiviral transduction effectiveness.67

Risk of insertional mutagenesis: Lentiviral vectors are deemed safer than earlier γ-retroviral vectors due to a lesser tendency to integrate near proto-oncogenes. However, the risk of insertional mutagenesis persists.68 This risk is especially critical in the context of SCD, because transduced cells must be maintained for the rest of their lives. To date, no incidences of vector-related leukemia have been recorded in SCD studies; nonetheless, long-term surveillance is critical, especially because patients treated in youth can live for decades after treatment.69

Durability of therapeutic expression: To get long-term clinical benefits, anti-sickling β-globin or fetal hemoglobin-inducing transgenes must be expressed consistently. Lentiviral vectors integrate stably into host genomes, however clonal drift over time may result in diminished transgene expression. In illnesses like SCD, where erythropoiesis is continuously accelerated, stem cell exhaustion or the proliferation of low-expressing clones may reduce treatment efficacy years after infusion. Current clinical trial follow-up data only extends for 7-9 years, raising questions about long-term durability.59

Cost and accessibility: The cost burden of lentiviral gene therapy is a significant constraint. Current estimates predict a per-patient cost of more than USD $2 million.70 This includes vector manufacturing, conditioning, hospitalization, and long-term monitoring. This renders the therapy unavailable to the majority of patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where SCD is most prevalent, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and India. The therapy's global impact will be restricted unless solutions for cost reduction and scalable distribution are implemented.71

Psycho-social and reproductive implications: Myeloablative conditioning and transplantation necessitate extensive hospitalization, which can severely impair education, job, and family life. Furthermore, busulfan and related regimens are gonadotoxic, causing reproductive problems that necessitate counseling and, if possible, fertility preservation prior to therapy Psychosocial stress, such as fear of relapse and concern regarding long-term safety, can also have an impact on patients' quality of life.72

While lentiviral gene therapy for SCD is a game-changing therapeutic discovery, considerable obstacles remain in the areas of safe stem cell mobilization, vector manufacturing scale, conditioning toxicity, long-term safety, cost, and equitable access. Addressing these limitations would necessitate concerted breakthroughs in vector design, mobilization regimens, conditioning tactics, health system infrastructure, and international collaboration to ensure that the advantages of this technology reach the whole SCD population.

Lentiviral gene therapy (LVGT) has emerged as one of the most promising disease-modifying interventions for sickle cell disease (SCD), with multiple clinical trials demonstrating the ability to achieve sustained increases in anti-sickling hemoglobin and reduction in vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) frequency. Although early clinical success is promising, several ongoing innovations and future directions are poised to further optimize efficacy, safety, accessibility, and scalability.

Enhancing vector design and efficiency: Future improvements will primarily focus on refining lentiviral vectors to optimize transduction efficiency while lowering vector copy number (VCN) requirements. Higher efficiency allows for therapeutic outcomes with fewer doses of genetically engineered hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), potentially lowering the severity of conditioning regimes. Recent advancements include the introduction of self-inactivating (SIN) LTRs, enhanced internal promoters such erythroid-specific β-globin locus control region (LCR) elements, and codon optimization of the HBB transgene to optimize protein expression.41

Furthermore, the addition of insulator elements may aid in mitigating insertional mutagenesis concerns, which are an important safety criterion for long-term use.66

Transition from myeloablative to reduced-intensity or non-myeloablative conditioning: The current dependence on myeloablative busulfan-based regimen has major toxicity risks, particularly in patients with organ dysfunction caused by chronic SCD. Antibody-drug conjugate-based conditioning (e.g., anti-CD117 or anti-CD45 monoclonal antibodies) is being investigated as a means of selectively depleting HSCs without the widespread damage of chemotherapy.73 These focused approaches may make LVGT safer for youngsters, the elderly, and patients with comorbidities.

Manufacturing scale-up and cost reduction: The extraordinarily high cost of LVGT is a significant barrier to global SCD management. Advances in vector production, such as producer cell lines with stable vector component integration, serum-free bioreactor technologies, and enhanced purification, are predicted to drastically lower prices. Parallel initiatives in point-of-care manufacturing could enable treatment in regional centres rather than central industrial-scale production.74

With ongoing trials (e.g., Bluebird Bio's LentiGlobin BB305, Aruvant's ARU-1801) reporting stable transfusion independence and VOC decrease, LVGT for SCD is moving from experimental to potentially curative standard of therapy in high-income nations. Future advances in vector design, conditioning regimens, and manufacturing efficiency will be critical to increasing worldwide access while ensuring long-term safety.

Lentiviral gene therapy has emerged as one of the most promising and potentially transformative strategies for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. By introducing functional β-globin genes or reactivating fetal hemoglobin production in autologous hematopoietic stem cells, this approach addresses the root genetic cause rather than merely alleviating symptoms. Advances in vector design such as self-inactivating backbones, lineage-specific promoters, and improved transduction protocols have substantially enhanced the safety, efficiency, and durability of gene expression. Clinical studies have demonstrated sustained correction of hemoglobin levels, reduced hemolysis, and a marked decline in vaso-occlusive crises, highlighting the therapy’s capacity for long-term disease modification.

Despite these breakthroughs, key challenges remain before lentiviral gene therapy can achieve global clinical impact. High manufacturing costs, the toxicity and intensity of current myeloablative conditioning regimens, and the need for sophisticated laboratory infrastructure limit its accessibility, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where the burden of sickle cell anemia is greatest. Furthermore, long-term monitoring is essential to fully establish the durability and safety of gene-modified cells over decades.

Future efforts should focus on optimizing vector potency while minimizing insertional mutagenesis risks, developing less toxic or non-genotoxic conditioning methods, and implementing scalable, cost-effective manufacturing platforms. Integration with emerging technologies such as base editing, prime editing, and in vivo gene delivery may further enhance treatment outcomes and expand patient eligibility.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Mitra, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.