Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Mini Review Volume 10 Issue 1

1Respiratory Department, Hospital Médica Sur, Mexico

2Grupo Mexicano para el estudio de las enfermedades hepaticas, Mexico

3Centro Respiratorio de México, Mexico

4Qigenix, USA

Correspondence: Peter Hollands PhD (Cantab), Qigenix, 6183 Paseo del Norte, Suite 260, Carlsbad, California, USA

Received: June 06, 2025 | Published: July 21, 2025

Citation: Sansores RH, Poo JL, Domínguez-Arellano S, et al. Human very small embryonic-like (hVSEL) stem cells and the reversal of advanced liver fibrosis. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):156-159. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00199

Background & aims: SONG Laser activated autologous hVSEL stem cells have shown benefits in a range of diseases including osteoporosis, spinal disk repair and neurological disorders. The aim of this work is to assess the potential role of SONG Laser activated autologous hVSEL stem cells in the treatment of liver fibrosis. The patient had liver fibrosis following previous Hepatitis C infection.

Approach & results: The hVSEL stem cells were obtained from peripheral blood and activated with the SONG Laser. The SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells were returned to the patient by the intravenous route. The SONG Laser was then applied directly to the patient in the region of the liver. The patient was assessed by pre- and post-treatment liver biopsies. The pre-treatment liver biopsy showed Grade 4 liver fibrosis. The post-treatment liver biopsy showed Grade 1-2 liver fibrosis. No adverse events occurred and the patient remains stable.

Conclusion: This is the first report of the reversal of liver fibrosis using SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells. Further studies are required to fully assess the safety and efficacy of SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells in liver fibrosis.

Keywords: regenerative medicine, pluripotent, laser, stem cells, liver disease

hVSEL stem cells, human very small embryonic like stem cells; PRP, platelet rich plasma; SONG laser, strachan ovokaitys node generator laser; US, ultrasound; TE, transient elastography; DAA, Direct-acting antiviral agent; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virologic response; HSC, haemopoietic stem cell; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell; BM, bone marrow

Fibrosis and/or hepatic cirrhosis may be secondary to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that globally, over 50 million individuals are affected, with nearly one million new infections occurring each year. WHO reported that 242,000 people died from hepatitis C in 2022.2 Consequently, given that its global prevalence averages 3%, hepatitis C infection is regarded as a significant public health issue worldwide.

Available treatments for HCV were limited or insufficient until the introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAA). In the early stages of hepatic fibrosis, therapy with DAA can eliminate the virus and may aid in the total or partial reversal of fibrosis.3-4 However, even with successful antiviral treatment, persistent fibrosis causes decreased quality of life and can ultimately lead to death. Antifibrotic therapies for hepatic fibrosis, such as pirfenidone, have recently shown improvements and reductions in hepatic fibrosis.5 However, the quest for more antifibrotic interventions, including complete relief and curing of hepatic fibrosis, remains an unmet goal requiring further research.6,7

Stem Cells are a type of cell that can self-renew many times, becoming highly differentiated and specialized in one progeny. They exist in all body tissues from embryogenesis to adulthood and are thought to help maintain and repair tissue in specific circumstances.8

Ratajczak et al.,9 described a population of human very small embryonic-like stem cells (hVSEL) stem cells identified in adult tissues. These hVSEL stem cells express several markers characteristic of embryonic and primordial germ cells, leading the authors to propose that they exist early in life as a dormant pool of embryonic/pluripotent normal stem cells. Since this description, the existence of hVSEL stem cells has been widely confirmed. hVSEL stem cells are small cells, measuring approximately 5–7 μm in humans and are capable of entering all body tissues. They occupy a top position in the stem cell hierarchy within normal bone marrow, giving rise to haemopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). It has been shown that hVSEL stem cells can grow in a culture medium, maintaining their pluripotency and differentiate into specialized cells.10 These observations suggest that they could be used for therapeutic purposes in regenerative medicine.11 Some publications indicate that these purified hVSEL stem cells may benefit some diseases.12,13 Despite these observations, it is not easy to activate these cells, transform them from quiescence to cellular activity, and eventually use them for therapeutic purposes.

In 2009, a 42-year-old woman with a body mass index of 22 was diagnosed with hepatitis C following the incidental discovery of mild, persistent abnormalities in liver function tests during a routine check-up. At the time of diagnosis, she reported experiencing isolated symptoms of chronic tiredness and fatigue. She had a history of blood transfusion as a newborn but otherwise led a normal life, including two pregnancies at ages 23 and 30. Testing revealed that the hepatitis C virus was not detected in either of her children, who were 20 and 13 years old at the time of writing, respectively.

The patient underwent several evaluations, including standard ultrasonography (US), transient elastography (TE), biomarker analysis, and liver biopsy.

Following HCV treatment, the patient expressed scepticism regarding her short- and long-term prognosis, acknowledging both the potential for reversibility and the risk of worsening fibrosis. Furthermore, she was aware of her Grade 4 classification based on TE results and reported a diminished quality of life. In 2022 she was advised to consider an alternative safe treatment involving stem cells.

The patient provided informed consent before receiving the SONG Laser activated autologous hVSEL stem cells, which involves an autologous PRP procedure. The procedure is closed with minimal manipulation, it therefore carries a low risk and does not require approval from an Ethical Committee.

Six 10 mL PRP tubes (Qigenix, Carlsbad, USA) of peripheral blood were drawn to obtain hVSEL stem cells, from the antecubital vein, and then placed in a centrifuge (Qigenix, Carlsbad, USA) programmed to accelerate to 3500 rpm for 10 minutes. The tubes contain an anticoagulant which is mixed into the freshly drawn blood to prevent clotting. As the cells are centrifuged, red blood cells and potentially inflammatory white blood cells are drawn through a special gel to remove and segregate them, giving rise to PRP containing plasma, platelets, growth factors, cytokines and hVSEL stem cells. The PRP was collected from each tube resulting in PRP from 6 centrifuged tubes being transferred into two 20 mL syringes. The average yield of each PRP tube was 7 mL of PRP from 10 mL of blood sample. For the 6-tube drawing, the resulting yield of PRP was about 42 mL altogether, divided into two collection syringes of approximately 21 mL each.14

To activate the hVSEL stem cells, each syringe of PRP was held in front of the SONG-modulated laser beam and as close as possible to the optical device without touching it.15 The two syringes were slowly rotated and moved up and down through the beam for 3 minutes each. The PRP containing the hVSEL stem cells was infused into the patient immediately after activation. The infusion was done over 3 to 4 minutes for each syringe sample (approximately 42 mL). During the infusion process, the beam from the SONG-modulated laser was directed at the area of the liver anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects for two minutes each.

All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul.

The patient agreed to be treated with her own PRP exposed to SONG-modulated laser light with the assumption that it would induce activation and proliferation of her dormant hVSEL stem cells with the hypothesis of potential hepatic regeneration.

Pre-treatment blood work revealed normal albumin (3.8 g per dL), a normal platelet count of (297 × 10³ per µL), aspartate transaminase (AST) at 72 U/L (reference range 15-41), alanine transaminase (ALT) at 100 U/L (reference range of 15-54), as well as normal bilirubin and prothrombin time (PT)

Hepatitis C virus diagnosis was made with a real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay which quantified hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA, at 2,320,000 IU/mL (6.73 Log IU/mL) identifying genotype 1b.

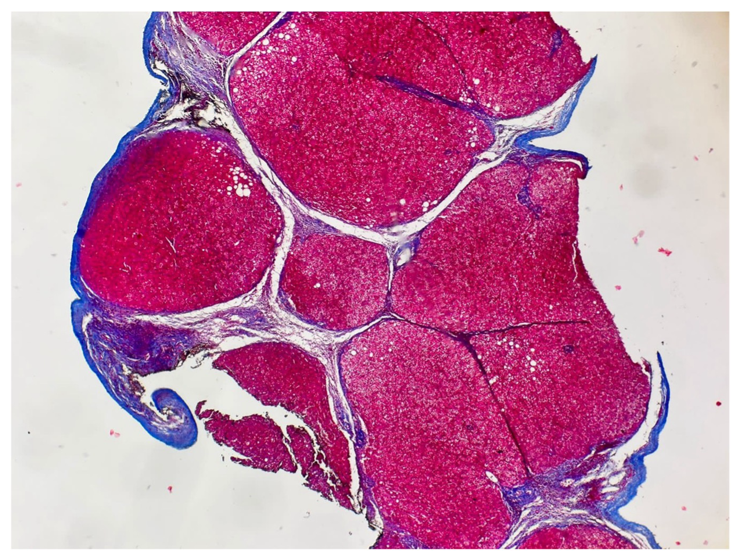

Ultrasound findings showed indirect data on liver cirrhosis, including scarce hepatic nodularity and coarseness, and no signs of portal hypertension. TE indicated Grade 4 hepatic fibrosis (see Table 1), consistent with the liver biopsy findings (see Figure 1). The fibrotest analysis yielded non-specific results, mainly due to the normal platelet count.

Figure 1 A wedge liver biopsy, performed before treatment for hepatitis C virus (2010), shows fibrotic portal tracts and regenerative nodules, a characteristic finding of cirrhosis, an advanced stage of liver fibrosis, visualized with a Masson trichrome stain.

|

Dates of evaluation |

12-May-2021 |

26-Ago-2022 |

21-Feb-2024 |

18-Oct-2024 |

13-Jun-2025 |

|

Medium |

12.7 |

6,2 |

7.5 |

7.0 |

7.7 |

|

IQR |

1.2 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

|

Fibrosis score |

F4 |

F1 |

F2 |

F2 |

F2 |

Table 1 Liver stiffness measurement evolution before and after SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cell treatment

The patient received treatment for Hepatitis C including a 22-week course of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PEG/RBV), which resulted in partial elimination of HCV viral load (maximum decrease to 4,170 IU/mL [3.62 Log IU/mL]).

However, treatment was discontinued due to severe side effects, including fever and a persistent, intensely pruritic skin rash, described by the patient as “unbearable” due to itching. The patient was prescribed prednisone at variable doses, starting at 40 mg daily for one month, followed by a two-month progressive taper to manage the itching and rash.

As no further treatment options were available in Mexico at that time her HCV viral load increased to 4,520,000 IU/mL. In 2017, she was recommended to try a combination of velpatasvir/sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral agent (DAA). She took it once a day for 12 weeks achieving HCV elimination and a sustained virologic response (SVR) that persisted for at least three years post-treatment.

Following HCV elimination, hepatic enzyme levels normalized. However, a TE performed one year after DAA treatment revealed persistent Grade 4 fibrosis. The patient continued to experience mild chronic headaches, tiredness, reduced exercise endurance due to mild chronic fatigue and weakness, and mild, nonspecific appetite loss. No cirrhosis-related complications, such as splenomegaly, portal hypertension, or ascites, were observed.

The patient reported initial symptomatic improvement within the first few weeks of SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cell therapy; after six months, she described significant clinical benefits, including resolution of headaches, malaise, and fatigue, as well as improved appetite and physical fitness. Hepatic enzyme levels remained within the normal range. Transient elastography (TE) demonstrated improvement from Grade 4 to Grade 1-2 (Table 1). A second liver biopsy, obtained incidentally two years after the hVSEL stem cell procedure during a cholecystectomy, revealed also a decrease in liver fibrosis to Grade 1-2 (Figure 2).

This is the first report of the use of SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells to treat hepatic fibrosis. The efficacy of the procedure was assessed by using the best-recognized tests (histopathologic and TE) before and following the infusion of SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells.

Using stem cells to treat hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis is not a new concept.16 Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) have been the most frequently researched option for treating liver disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials17 found improvements in markers of hepatic function when using BM-MSC. However, most publications have highlighted an increase in mortality rates. This was mainly because the procedure was performed when the disease had progressed.

Approximately 70% of the worldwide population is affected by chronic hepatitis C, which is one of the leading causes of fibrosis and hepatic cirrhosis2. These complications may show reasonable improvement rates as high as 88% after antiviral treatment. However, after cirrhosis is established, depending on several factors,18 a patient may remain clinically healthy with no complications for years19 or may progress to decompensation.20

Despite having achieved viral clearance with DAA treatment four years earlier, the patient in this study continued to experience mild malaise and presented a transient elastography (TE) score of Grade 4. Consequently, she sought alternative treatments. After six to twelve months of treatment with SONG Laser activated hVESEL stem cells, TE scores improved from Grade 4 to Grade 1-2, and a liver biopsy performed two years after treatment also showed histological improvement. Simultaneously, liver enzyme levels normalized, and the patient's general symptoms of malaise remitted.

We understand that before attributing clinical improvement and reduction in liver fibrosis to SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cell therapy, we must consider other relevant factors which might have been influenced the regression of liver fibrosis. These include baseline fibrosis stage, as patients with more advanced fibrosis (Grade 3 or Grade 4, i.e., bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis) are less likely to experience complete regression compared to those with milder fibrosis Grade 2 to Grade 0. Likewise, older patients tend to have slower fibrosis regression and comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, obesity, alcohol consumption, and other liver diseases can hinder fibrosis regression.

In summary, based on the findings of this clinical case, we believe that further clinical studies (a double-blind clinical trial) would be warranted to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety of SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cells in patients with liver damage secondary to chronic hepatitis C infection who, despite a sustained viral response, continue to have persistent liver fibrosis. In addition, longer follow-up periods (more than 5 years) are needed to fully assess the degree of fibrosis regression after SONG Laser activated hVSEL stem cell procedure.

The safety of the procedure and the possibility of its use in conjunction with other pharmacological alternatives for clinical and histological improvement are noteworthy in this case. We do not know whether the efficacy obtained will only be observed in patients with compensated cirrhosis or could be used in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Without doubt, further research is clearly needed.

None.

None.

Todd Ovokaitys and Peter Hollands are CEO and CSO of Qigenix respectively.

©2025 Sansores, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.