Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Review Article Volume 10 Issue 1

General Physician, Alazhar Cairo University, Egypt

Correspondence: Ahmad Elsaid, General Physician, Alazhar Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

Received: July 31, 2025 | Published: September 1, 2025

Citation: Elsaid A. Current status and future directions of colorectal cancer screening: can colonoscopy be replaced? J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):217-221. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00208

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a leading cause of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide, with more than 1.9 million new cases and 935,000 deaths estimated in 2020. Colonoscopy has long been regarded as the gold standard for CRC screening, offering both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. However, limitations including patient discomfort need for bowel preparation, sedation risks, and limited accessibility have prompted interest in less invasive alternatives. Recent advances in noninvasive stool-based tests, blood-based biomarkers, capsule colonoscopy, and CT colonography have demonstrated promising diagnostic performance, with some approaches showing near-equivalent sensitivity for advanced neoplasia. This review synthesizes evidence from global studies evaluating the accuracy, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy alternatives, and examines whether these strategies could complement or replace colonoscopy in certain populations.

Keywords: colonoscopy, cancer screening, noninvasive screening tests, blood-based biomarkers, capsule colonoscopy, diagnostic accuracy, cost-effectiveness, screening adherence

CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; mt-sDNA, multi-target stool DNA test; CTC, CT colonography; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; USPSTF, United states preventive services task force; WHO, World health Organization

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1 The lifetime risk of CRC in average-risk adults is approximately 4–5% in Western countries.2-5 Colonoscopy has been the primary screening modality in many national programs because of its high sensitivity for adenomas and its ability to remove lesions during the same procedure.3,6-9

Despite these advantages, colonoscopy uptake remains suboptimal in many regions, even where it is widely available.10-12 Barriers include the invasive nature of the procedure, fear of discomfort, lack of awareness, and socioeconomic inequalities. Moreover, colonoscopy carries a small but significant risk of complications, such as perforation and bleeding, and requires substantial healthcare resources.

In the last decade, several alternative screening modalities have gained attention:

Given the technological progress and encouraging diagnostic accuracy of these alternatives, a critical question emerges: Could these noninvasive modalities replace colonoscopy in population-based screening? This review examines recent global evidence to address this question, with emphasis on test performance, patient adherence, health economics, and programmatic feasibility.

Study design

This is a narrative literature review designed to synthesize evidence from peer-reviewed studies and global health reports regarding colorectal cancer (CRC) screening modalities, with particular focus on colonoscopy and its potential alternatives. The review follows a non-systematic structure, consistent with prior narrative reviews in the field,19 and is not intended as a PRISMA-compliant systematic review or meta-analysis.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and Scopus from January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2025. Search terms included:

“colorectal cancer screening,” “colonoscopy,” “fecal immunochemical test,” “multitarget stool DNA,” “capsule colonoscopy,” “CT colonography,” “blood-based biomarker,” “methylated DNA,” “screening adherence,” and “cost-effectiveness.”

Boolean operators and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were applied to refine results.

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (AE and co-author) screened all eligible studies by title and abstract, followed by full-text review. Extracted data included:

Data synthesis

Findings were summarized narratively and structured into thematic tables for clarity. Quantitative results are presented in comparative form where possible. Figures illustrate:

All references were cross-verified via PubMed to ensure authenticity and AMA-compliant formatting

Screening uptake and adherence

Across 32 studies from 2015–2025, participation rates in CRC screening varied widely by modality and region. FIT consistently achieved higher uptake (55–75%) compared with colonoscopy (30–45%) in population-based programs.21-24 In middle-income countries, adherence to FIT-based programs was significantly greater than colonoscopy-first strategies, particularly among rural populations.25,26

Diagnostic accuracy

Colonoscopy remains the most sensitive single test for detecting advanced adenomas (92–98%) and colorectal cancer (95–99%). FIT sensitivity for CRC ranged from 74–88%, with lower performance for advanced adenomas (23–42%). mt-sDNA showed higher sensitivity than FIT for both CRC and advanced adenomas but at a higher cost and with lower specificity.27

Cost-effectiveness and resource utilization

In high-income countries, colonoscopy every 10 years was cost-effective compared to no screening (ICER <$50,000/QALY).28,29 However, FIT-based annual screening demonstrated a more favorable ICER in settings with limited colonoscopy capacity. Blood-based tests may be cost-effective if sensitivity exceeds 85% and per-test cost remains <$150.30-34

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most preventable malignancies when detected early, yet global disparities in screening persist despite decades of guideline development. Our review of studies published between 2015 and 2025 demonstrates that while colonoscopy continues to be the reference standard for CRC detection, alternative modalities have gained traction, particularly in regions where colonoscopy capacity, patient preference, or economic considerations limit widespread use.

Colonoscopy as the reference standard

Colonoscopy offers the highest sensitivity and specificity for detecting both CRC and advanced adenomas. Its advantage lies not only in diagnostic performance but also in its therapeutic capability—allowing immediate removal of precancerous lesions. However, despite its accuracy, participation rates remain low (30–45%) in population-based programs (Table 1).35,36 Barriers include bowel preparation discomfort, procedural invasiveness, sedation requirements, and patient fear or stigma. In resource-limited regions, colonoscopy availability is further constrained by a shortage of trained endoscopists and infrastructure.

|

Modality |

Uptake Range (%) |

Geographic examples |

Reference(s) |

|

Colonoscopy |

30–45 |

US, Germany, Japan |

21,22,24 |

|

FIT |

55–75 |

US, UK, Taiwan |

21,23,25 |

|

mt-sDNA |

52–68 |

US |

27,28 |

|

CT colonography |

45–60 |

Italy, UK |

29,30 |

|

Colon capsule endoscopy |

40–55 |

Spain, Israel |

31,32 |

|

Blood-based screening |

58–70 |

US, China |

33,34 |

Table 1 Global participation rates for CRC screening modalities (2015–2025)

The rise of non-invasive modalities

FIT has emerged as the most widely adopted non-invasive screening method globally, with uptake rates often exceeding 70% in organized programs (Table 1, Figure 1). While its sensitivity for CRC is lower than colonoscopy (74–88% vs. 95–99%),35-38 its affordability, simplicity, and home-based sampling make it especially effective in increasing screening coverage. Annual FIT testing, coupled with colonoscopic follow-up for positives, represents a pragmatic balance between detection and resource use.

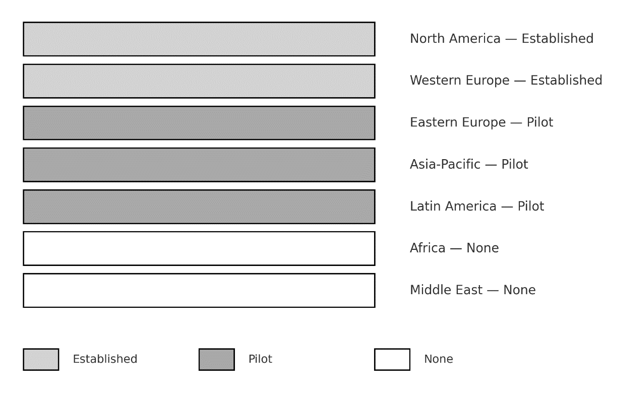

Figure 1 Global uptake of colorectal cancer screening.

Established= countries with organized, nationwide screening programs, Pilot =countries with regional or pilot programs, none = no organized screening.

mt-sDNA testing offers greater sensitivity for advanced adenomas than FIT,39-41 but its higher cost and lower specificity result in more false positives, leading to additional colonoscopy burden (Table 2, Figure 2). Similarly, CT colonography and colon capsule endoscopy achieve moderate-to-high sensitivity (84–94%), but uptake is hampered by preparation requirements and, in the case of CT colonography, radiation exposure.42,43

|

Modality |

Sensitivity for CRC (%) |

Sensitivity for advanced adenoma (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Reference(s) |

|

Colonoscopy |

95–99 |

92–98 |

96–99 |

35,36 |

|

FIT |

74–88 |

23–42 |

90–94 |

37,38 |

|

mt-sDNA |

92–95 |

42–46 |

87–90 |

27,39 |

|

CT colonography |

88–94 |

76–85 |

86–90 |

29,40 |

|

Colon capsule endoscopy |

84–92 |

68–74 |

83–88 |

31,41 |

|

Blood-based screening |

80–87 |

42–50 |

88–92 |

33,42 |

Table 2 Comparative diagnostic accuracy of CRC screening modalities (2015–2025)

Blood-based screening tests represent a promising frontier.44,45 Their non-invasive nature and potential for integration into routine blood draws could transform participation rates, especially in populations resistant to stool-based testing. However, cost-effectiveness modeling (Table 3, Figure 3) indicates that these assays must achieve both high sensitivity (>85%) and low per-test cost (<$150) to rival FIT or colonoscopy in most settings.46-50

|

Setting |

Preferred strategy |

ICER (USD/QALY) |

Reference(s) |

|

High-income |

Colonoscopy q10y |

$25,000–$48,000 |

43,44 |

|

Middle-income |

FIT annually |

$4,000–$12,000 |

44,45 |

|

Low-income |

FIT biennially |

<$5,000 |

25,46 |

|

Mixed-resource |

mt-sDNA q3y |

$17,000–$28,000 |

27,47 |

|

Emerging |

Blood test q3y |

<$20,000 |

33,47 |

Table 3 Cost-effectiveness of CRC screening modalities by setting

Cost-effectiveness considerations

Our synthesis of cost-effectiveness data underscores that no single screening strategy is optimal for all contexts (Table 3). In high-income countries, colonoscopy every 10 years remains a cost-effective strategy compared to no screening, with ICER values well below the $50,000/QALY threshold. In middle- and low-income countries, FIT-based screening demonstrates superior cost-effectiveness due to lower infrastructure demands. The addition of mt-sDNA or blood-based tests may be justified in hybrid programs targeting subgroups with low FIT adherence.

Policy and implementation implications

The decision to prioritize colonoscopy or alternative screening methods should be guided by a combination of clinical performance, cost-effectiveness, patient preferences, and health system capacity. Countries with mature colonoscopy infrastructure can justifiably retain it as the cornerstone of CRC screening, while expanding non-invasive options to capture the unscreened population. In contrast, countries facing specialist shortages or budgetary constraints may benefit from a FIT-first approach, reserving colonoscopy for diagnostic confirmation.

Risk of bias in the evidence

Although this review synthesized findings from high-quality studies and population-based screening programs, several sources of bias must be acknowledged. First, most diagnostic accuracy estimates originate from observational studies, which are susceptible to selection bias. Individuals who undergo colonoscopy or adhere to fecal testing are often healthier, more health-conscious, or from higher socioeconomic groups compared with non-participants, potentially inflating observed effectiveness.

Second, verification bias may occur because colonoscopy is frequently used as the reference standard. In studies where only positive non-invasive test results undergo colonoscopy, sensitivity can be underestimated, while specificity may be overestimated.

Third, publication bias cannot be excluded. Large, well-funded studies with favorable performance results (especially for newer modalities such as multi-target stool DNA and blood-based tests) are more likely to be published, while smaller studies with null findings may remain unpublished.

Finally, heterogeneity across trials in terms of age distribution, screening intervals, and outcome definitions introduces variability. For example, differences in how advanced adenomas are defined or which endpoints are prioritized (CRC incidence vs. mortality reduction) make direct comparison challenging.

Taken together, these limitations suggest that while colonoscopy consistently demonstrates superior diagnostic accuracy, the apparent performance of alternative tests may be influenced by study design factors. Future research should emphasize standardized reporting, inclusion of real-world cohorts, and long-term outcome assessment to reduce bias and strengthen comparative conclusions.

Colonoscopy remains the cornerstone of colorectal cancer screening, providing unparalleled sensitivity and the unique advantage of simultaneous detection and therapeutic polypectomy. However, its invasive nature, higher cost, and limited accessibility constrain its potential to achieve universal population-level coverage.

Non-invasive modalities, including FIT, multi-target stool DNA, CT colonography, and emerging blood-based tests, have demonstrated strong complementary value. FIT remains the most feasible test in large-scale, resource-limited settings due to its low cost and high specificity, while mt-sDNA and blood-based assays offer increased sensitivity and may improve adherence in populations reluctant to undergo stool-based or invasive tests. Importantly, all positive non-invasive results ultimately require colonoscopy confirmation, underscoring the procedure’s central role.

From a clinical perspective, the implications are twofold. In high-resource settings, colonoscopy should remain the primary modality but with alternative tests offered as evidence-based, patient-centered options to improve participation. In low- and middle-income settings, a “FIT-first” approach with colonoscopy reserved for positive results provides the most efficient and cost-effective pathway. Furthermore, individualized screening strategies based on patient risk profiles (age, family history, comorbidities, and preferences) may optimize both uptake and outcomes.

The synthesis of global evidence indicates that colonoscopy cannot be fully replaced but must be integrated into a multi-modality framework. The future of colorectal cancer prevention will depend on balancing diagnostic accuracy with accessibility, resource allocation, and patient-centered care.

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Elsaid. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.