Journal of

eISSN: 2475-5540

Review Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1UCLA Brain Tumor Imaging Laboratory (BTIL), Center for Computer Vision and Imaging Biomarkers, University of California, USA

2Department of Radiological Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, USA

3Department of Bioengineering, Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science, University of California, USA

Correspondence: Bill Tawil, Department of Bioengineering, UCLA School of Engineering, 420 Westwood Plaza, Room 5121, Engineering V. P.O. Box: 951600, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1600, USA

Received: September 27, 2025 | Published: October 27, 2025

Citation: Kim, Asher, Bill T. A review on biohybrid bone grafts for critical-sized defects. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;10(1):226‒237. DOI: 10.15406/jsrt.2025.10.00210

The clinical demand for bone grafts continues to rise due to trauma, cancer resections, and age-related degeneration, placing significant pressure on current treatment strategies. Autografts remain the gold standard by providing osteogenic cells, extracellular matrix, and osteoinductive signaling, yet their use is limited by donor-site morbidity, finite supply, and additional surgical burden. These constraints have driven the development of synthetic and bioengineered substitutes. Among them, biohybrid bone grafts, biodegradable scaffolds integrated with growth factors, peptides, or stem cells, have emerged as a promising class that combines structural reinforcement with controlled biological activity.

This review examines the biological foundations of bone repair and the pathophysiology of critical-sized defects, outlines the limitations of autografts, allografts, and purely synthetic substitutes, and surveys scaffold chemistries (ceramics, polymers, and composites), delivery formats (blocks, granules, moldable putties, and injectables), and representative commercial products across graft classes. Market analysis indicates that the global bone grafts and substitutes sector was valued at approximately USD 3.20 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 5.68 billion by 2034 (CAGR ~5.9%), with North America leading and Asia–Pacific exhibiting the fastest growth. Advances in 3D printing, injectable composites, peptide- and growth factor–enhanced matrices, and stem cell–based constructs are highlighted as key directions shaping next-generation solutions. Together, these insights underscore the need to integrate mechanical integrity, vascularization, and immunomodulation in scalable, off-the-shelf implants that align with minimally invasive surgical workflows and are adaptable to patient-specific anatomy, positioning biohybrid strategies to redefine the treatment of large skeletal defects.

Keywords: biohybrid bone grafts, critical-sized defects, osteoconduction, osteoinduction, bone regeneration, tissue engineering, regenerative orthopedics, scaffold composites, vascularization, immunomodulation

three dimensional (3D), extracellular matrix (ECM), additive manufacturing (AM), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computer-aided design (CAD), computer-aided manufacturing (CAM), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), demineralized bone matrix (DBM), hydroxyapatite (HA), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP), bioactive glass (BAG), growth factor–enhanced scaffolds (GFES), multiphasic scaffolds (MPS), critical-sized defect (CSD).

In recent years, biohybrid bone grafts for critical-sized bone defects (CSDs) have been gaining traction in orthopedic surgery and regenerative medicine.1,2 Recent data underscore the unmet need: bone is the second most commonly transplanted tissue worldwide (>2 million grafting procedures annually), skeletal defect care exceeds USD 5 billion in annual U.S. spending, and segmental long-bone injuries continue to exhibit substantial nonunion rates (approximately 5–10% across fractures and higher in CSDs).3–5 Biohybrid grafts present an opportunity to address the limitations of autologous bone, which remains the gold standard for osteogenic cells, extracellular matrix, and inductive signaling but is limited by donor-site morbidity, finite supply, and added operative burden.3,4,86–7

Biohybrid bone grafts combine an osteoconductive scaffold with osteoinductive cues and, in some cases, osteogenic cells, to reconstitute the tissue engineering triad and promote vascularized regeneration.8-10 Contemporary platforms integrate calcium phosphate ceramics, biodegradable polymers, and polymer–ceramic composites to balance mechanical reinforcement with regulated resorption.11 These constructs are produced in conforming formats such as blocks, granules, moldable putties, and injectables, suitable for load-bearing and non-load-bearing CSDs, and aligned with evolving surgical workflows.12 This review examines the biological principles of bone repair and CSD pathophysiology, evaluates commercial and developmental biohybrid graft technologies, and analyzes market and regulatory trends shaping next-generation orthopedic grafts.12

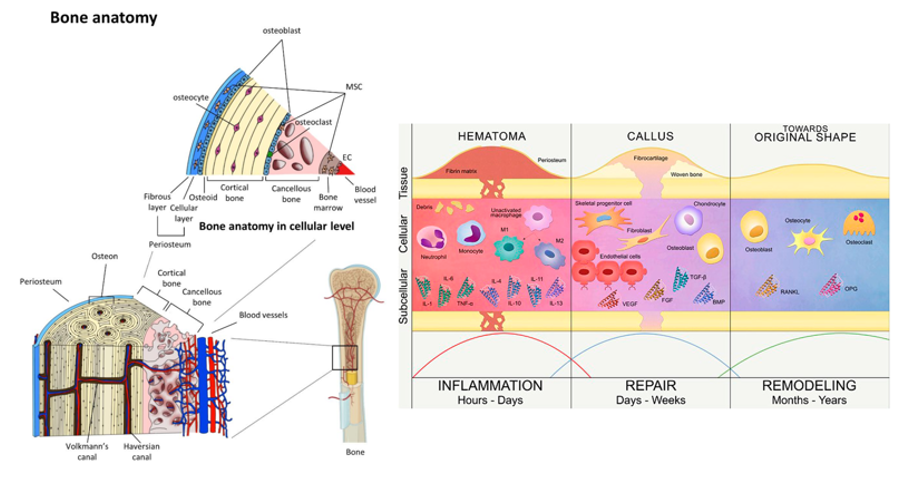

Physiology of bone: hierarchical structure and mechanics: Bone is a specialized connective tissue that provides mechanical support, hematopoiesis, mineral homeostasis, and organ protection through a hierarchical architecture spanning nanoscale collagen–hydroxyapatite composites to macroscopic anatomical structures.13 Type I collagen fibrils mineralized with hydroxyapatite impart tensile and compressive strength at the nanoscale, while their assembly into lamellae, osteons (cortical bone), and trabeculae (cancellous bone) generates anisotropic mechanics suited to diverse loading conditions.14,15 Cortical bone comprises ~80% of skeletal mass and confers rigidity, while cancellous bone supports metabolic activity; together they enable high load-bearing with dynamic remodeling.16–18 Figure 1 illustrates the multiscale architecture underlying bone’s dual roles of strength and regeneration.14

Cellular regulation and remodeling: Bone homeostasis is regulated by osteoblasts (matrix synthesis; mesenchymal origin), osteoclasts (resorption; hematopoietic origin), and osteocytes (embedded mechanosensors derived from osteoblasts).19 Osteocytes regulate remodeling through pathways such as RANK/RANKL and sclerostin, coupling mechanical cues to cellular activity.20 Following injury, repair progresses through hematoma and inflammation, soft callus formation, hard callus ossification, and remodeling into lamellar bone.21 In load-bearing regions, endochondral ossification predominates, recapitulating developmental programs.22 Figure 2 contrasts organized fracture healing with failed repair in CSDs.21

Figure 2 Normal fracture healing versus critical-sized defect repair.21

The image shows the differences between normal fracture healing, which progresses through inflammation, callus formation, and remodeling, and impaired healing of critical-sized defects, where fibrous tissue forms instead of new bone.21

Limits of regeneration and definition of CSDs: Despite robust regenerative capacity, bone repair has limits. CSDs are defined as the smallest defects unlikely to heal over a lifetime, thus exceeding intrinsic regenerative potential.23 In long bones, this is often operationalized as defects greater than 2.5 cm in length or involving more than 50% of the circumference.24 Nonunion in CSDs is driven by inadequate vascularization and insufficient osteoprogenitor cells at defect margins, favoring fibrous tissue over mineralized bridging.25 These constraints motivate the design of advanced graft substitutes capable of recapitulating the necessary biological, structural, and mechanical cues for complete regeneration.26

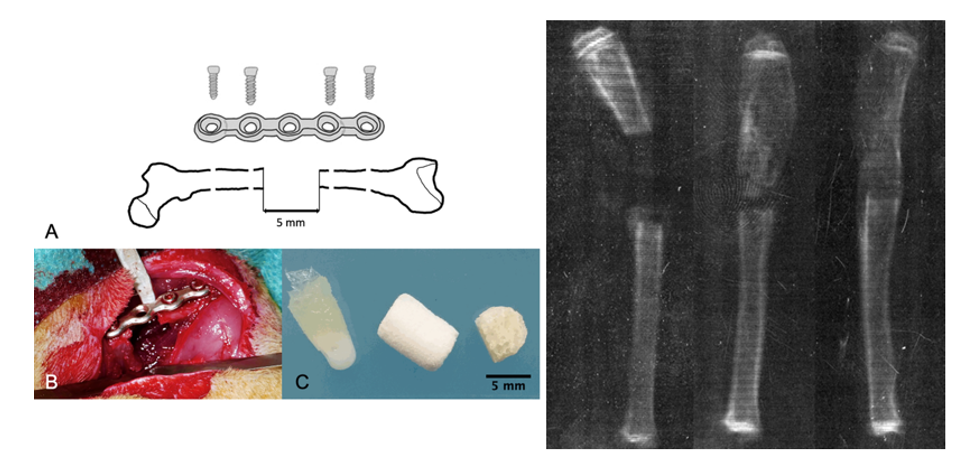

Pathophysiology of CSDs: Unlike typical fractures that progress through well-orchestrated phases, CSDs fail to initiate or sustain the regenerative cascade due to compromised vascularity, poor progenitor recruitment, and disrupted signaling gradients critical for endochondral ossification.26 Mechanical instability, ischemia, and a lack of osteoinductive signals further bias healing toward fibrous nonunion rather than bone regeneration.27,28 Figure 3 highlights the divergence between structured healing in standard fractures and impaired regeneration in CSDs.27

Figure 3 Rat femoral critical-sized defect model and graft outcomes.27

The image shows the establishment of a 5 mm femoral mid‑diaphyseal defect in a rat, including a schematic of defect creation and fixation, an intraoperative view, and scaffold material examples.27 A radiographic comparison highlights successful bone regeneration versus impaired repair.27

Models and translational benchmarks: Preclinical models are essential for mechanistic insight and for evaluating candidate therapies under controlled conditions. A widely used rat femoral CSD model (5 mm mid-diaphyseal defect stabilized with internal fixation) provides a reproducible platform to test graft materials in compromised healing environments.29 This model serves as a benchmark for scaffold-based validation.30 While autologous bone inherently provides osteogenesis, osteoinduction, and osteoconduction, its clinical deployment is limited by donor-site morbidity, finite availability, and added operative time.30 Accordingly, alternative strategies, such as the Masquelet-induced membrane technique and tissue-engineered scaffolds, have been developed to address biological limitations in these lesions.31 Biohybrid approaches that pair osteoconductive matrices with biologics and/or cells aim to restore the triad of mechanical stability, vascularity, and osteogenic stimulation necessary for successful repair, with ongoing work focused on translational models and patient-specific solutions to bridge bench-to-bedside adoption.32

Types of bone grafts: In CSD reconstruction, graft selection is the most critical step.33 Bone grafts are broadly classified by material origin into three categories: allografts, synthetics, and biohybrids.33,34

Allografts dominate global revenue due to broad clinical use, synthetics are gaining share because of scalability and predictable resorption, and biohybrids are emerging as next-generation solutions where enhanced biology is needed.34,37–39 Table 2 provides a comparative overview of mechanical versus biological (biohybrid) approaches for CSD repair.40

Graft properties essential for csd repair: An ideal graft must excel in three areas: deliverability and conformability, bioactivity and biocompatibility, and mechanical integrity with synchronized resorption.40,42,43

Deliverability and conformability:

Graft format and delivery modality strongly influence suitability for minimally invasive techniques and defect fit. Blocks, chips, and granules provide structural fill for large voids but require open surgery and adapt poorly to irregular geometries.42,44,45 Moldable putties and injectable pastes (e.g., calcium phosphate or collagen-based) enable precise placement, reduce operative time, and suit MIS workflows, but often lack load-sharing capacity in large segmental defects.45,46 A side-by-side comparison of delivery formats and clinical attributes is shown in Table 1.45

|

Feature |

Mechanical grafts |

Biological (biohybrid) grafts |

|

Composition |

β-TCP, HA, BCP, bioactive glass |

Scaffold + BMP/PDGF, peptides, or stem cells |

|

Osteoconduction |

✓✓✓ |

✓✓✓ |

|

Osteoinduction |

✗ |

✓✓ |

|

Osteogenesis |

✗ |

✓ (if cell-based) |

|

Structural support |

High |

Moderate to high (scaffold-dependent) |

|

Degradation control |

Tunable (ceramics, glass) |

Tunable (with polymer carriers) |

|

Common products |

Vitoss®, Actifuse®, NovaBone® |

Infuse®, Augment®, Trinity Evolution® |

|

FDA-approved uses |

Spine, trauma, dental |

Spine, foot/ankle fusion, long bone fractures. Despite advancements, autografts, typically harvested from the iliac crest, continue to set the clinical benchmark due to their unmatched osteogenic capacity |

|

Cost and handling |

Lower, easy storage |

Higher, cryostorage or special handling needed |

Table 1 Comparative delivery formats for bone grafts.56 The table summarizes differences between conventional delivery methods (blocks, chips, granules) and injectable formats (pastes, putties), highlighting their clinical applications, advantages, and limitations.

Bioactivity and biocompatibility:

Biological performance encompasses osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and, where applicable, osteogenesis.40,42,43 Synthetics (e.g., HA, β-TCP, bioactive glass) reliably support osteoconduction but lack inductive cues or viable cells.47–50 Allograft-derived DBM retains growth factors and can provide osteoinductive cues, while biohybrid platforms incorporate BMPs, PDGF, or cell populations (e.g., MSCs) to enhance recruitment, angiogenesis, and remodeling in compromised environments.51–53 Safety and consistency are critical: recombinant protein delivery (e.g., rhBMP-2) has been associated with ectopic bone formation and inflammation in some settings, emphasizing dose control and indication-specific use.54,55 Table 1 contrasts biological capabilities across classes, and Table 2 outlines representative products and attributes.66,41

|

Graft Type |

Key features |

Representative products |

|

Autografts |

Harvested from the patient's own body- Contains living cells- Osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive |

Iliac crest bone grafts- Local bone harvested during surgery |

|

Allografts |

Donor human bone- Processed to remove cells- Primarily osteoconductive |

Grafton® (Medtronic)- Puros® (Zimmer Biomet)- OraGraft® (LifeNet Health) |

|

Demineralized Bone Matrix (DBM) |

Acid-extracted allograft- Retains growth factors- Osteoinductive and osteoconductive |

DBX® (DePuy Synthes)- AlloMatrix® (Wright Medical)- Regenafil® (RTI Surgical) |

|

Synthetic Grafts |

Man-made materials (e.g., ceramics, polymers)- Osteoconductive- Variable resorption rates |

Vitoss® (Stryker)- Actifuse® (Baxter)- Cerament® (Bonesupport) |

|

Xenografts |

Derived from animal sources (e.g., bovine, porcine)- Processed to reduce immunogenicity- Primarily osteoconductive |

Bio-Oss® (Geistlich Pharma)- Endobon® (Zimmer Biomet) |

|

Growth Factor Enhanced Grafts |

Incorporate bioactive molecules (e.g., BMPs, PDGF)- Stimulate bone formation- Osteoinductive |

INFUSE® (Medtronic)- Augment® (Bioventus) |

|

Cell-Based Grafts |

Contain viable cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells)- Osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive |

Trinity Evolution® (Orthofix)- Osteocel® (NuVasive) |

Table 2 Major classes of bone grafts with defining features and representative FDA‑cleared commercial products. This table summarizes the principal graft categories used in orthopedic regeneration, including autografts, allografts, demineralized bone matrix (DBM), synthetic scaffolds, xenografts, growth factor–enhanced constructs, and cell‑based platforms. For each class, defining biological and clinical attributes are listed alongside representative FDA‑cleared or commercially available examples

Mechanical integrity and resorption:

For CSDs, especially in load-bearing sites, initial structural support, appropriate porosity, and degradation synchronized with host bone formation are essential.40,42,43 Ceramics such as β-TCP, HA, and BCP provide compressive strength and tunable resorption but may underperform where vascularity is limited or high toughness is required.47–50 Biohybrid strategies can pair mechanically competent scaffolds with inductive factors or cells to couple stability with regeneration, aiming to avoid premature loss of strength or persistent, non-resorbing remnants.56,57,58,59 Optimal selection is anatomy- and pathology-specific, guided by defect size, vascularity, load-bearing demands, and patient comorbidities.58,59

The global bone grafts and substitutes market has grown steadily and is projected to expand over the next decade.60 In 2024, the market was valued at approximately USD 3.20 billion, and it is forecasted to reach USD 5.68 billion by 2034, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.94%.60 This growth is driven by the increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders, the rising number of orthopedic interventions, and the growing adoption of tissue-engineered substitutes that minimize donor site morbidity compared to autografts.34 As shown in Figure 4, the market is expected to nearly double over the forecast period.60

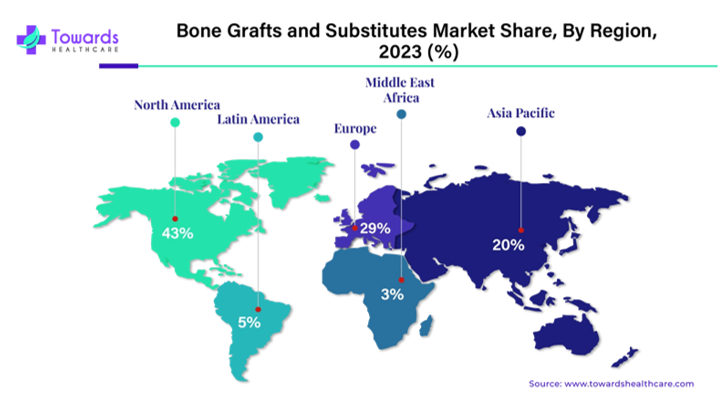

Regional market distribution: North America accounts for 47.6% of global revenue in 2024, driven by robust surgical infrastructure and high volumes of spinal, joint, and trauma procedures.61 Within North America, the United States alone generated over USD 1.25 billion in bone graft sales in 2024, with projections indicating an increase to USD 2.14 billion by 2034.61 In contrast, the Asia-Pacific region is anticipated to grow most rapidly, with a CAGR of 6.6%, largely driven by improved healthcare access and rising procedure rates in populous countries such as China and India.62 Figure 6 illustrates the 2024 regional distribution of market share, with North America leading, followed by Europe and Asia-Pacific.62

Market segmentation by material: By material, allografts remain the predominant graft type, generating USD 1,799.4 million in revenue in 2024, equivalent to 55.8% of the global market share.63,64 Their use in spinal, trauma, and revision surgeries is supported by mechanical stability and avoidance of donor site morbidity.63 However, drawbacks such as limited remodeling capacity and concerns about disease transmission have encouraged the adoption of synthetic substitutes.64 Synthetics represented USD 1,423.7 million (44.2% of revenue) in 2024, gaining traction for scalable production, predictable degradation, and low immunological risk.64,65 As shown in Table 3, synthetics have consistently increased in market penetration since 2022.11

|

Material |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

Allograft |

1,607.10 |

1,690.50 |

1,799.40 |

|

Synthetic |

1,274.20 |

1,346.40 |

1,423.70 |

Table 3 Global bone grafts and substitutes market revenue by material, 2022–2024.56 The table presents annual revenue (in USD millions) for allograft and synthetic graft segments, showing steady year-over-year growth across the observed period.

In addition, biohybrid grafts, synthetic scaffolds augmented with growth factors, peptides, or viable cells, are emerging as the fastest-growing segment. These constructs replicate native bone healing environments and are particularly advantageous for large or poorly vascularized defects.37,38,39 Examples include Medtronic’s INFUSE® (rhBMP-2) and Orthofix’s Trinity Evolution®, both of which highlight the regulatory and clinical emphasis on biologically enhanced grafts.55

Delivery formats: The mode of delivery has also influenced product adoption. Blocks, chips, and granules remain standard for open surgeries but adapt poorly to irregular geometries.67 In contrast, moldable putties and injectable formulations have gained significant clinical preference, especially in minimally invasive procedures.74 Injectables such as flowable calcium phosphate pastes conform to complex spaces, reduce operative time, and are well suited for trauma, dental, and spinal applications.45–46 Table 4 compares conventional and injectable graft modalities, summarizing their clinical strengths and limitations.46

|

Format |

Description |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Traditional Grafts |

Solid block, chip, or granule forms manually placed into defect site |

Provides structural support for large defects - Readily available formats |

Limited to open surgery - Poor fit to irregular geometries |

|

Moldable Putties |

Semi-solid, shapeable formulations used to fill gaps and conform to defect shape |

Easily applied - Conforms to irregular spaces - Reduced surgical time |

May lack mechanical integrity for load-bearing regions |

|

Injectable Grafts |

Flowable, syringe-delivered pastes (often calcium phosphate or collagen-based) |

Ideal for minimally invasive procedures - Precise delivery - Reduced trauma |

Limited applicability in large segmental defects - Lower mechanical strength |

Table 4 Comparative delivery formats for bone grafts57. The table compares traditional grafts (blocks, chips, granules), moldable putties, and injectable pastes in terms of format, description, advantages, and limitations, highlighting clinical trade-offs between structural support and minimally invasive handling.

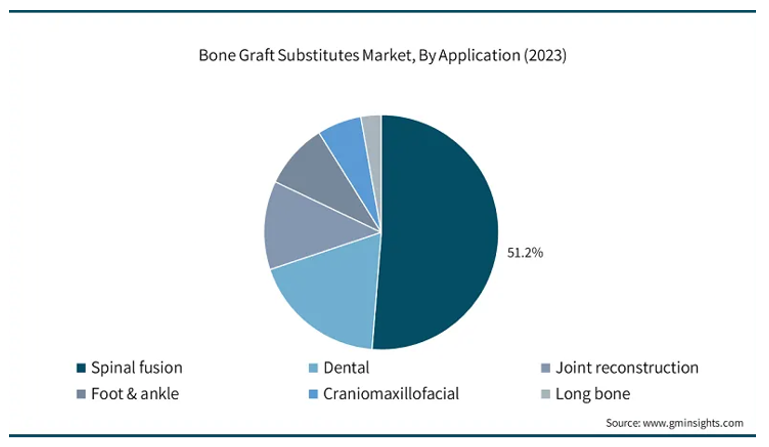

Clinical applications: Spinal fusion is the largest application (51% in 2023), but its share is projected to decline to 45% by 2034 as other indications grow.68–69 However, this proportion is expected to decline slightly to 45% by 2034 as other segments expand.68 Dental bone grafting represents the fastest-growing indication, projected to rise from 15% in 2023 to 25% by 2034, fueled by the increasing number of implant procedures and alveolar ridge augmentations in aging populations.70–71 Other major applications include joint reconstruction, orthopedic trauma, and craniomaxillofacial repair, each comprising between 7% and 12% of global market share.72,73 Figure 5 highlights the anticipated revenue distribution by application, emphasizing the accelerating growth in dental procedures.71

Figure 5 Anticipated revenue distribution by clinical application.71

The chart shows projected market revenue across major bone graft applications.61 Dental bone grafting demonstrates the fastest growth, while spinal fusion retains the largest, though gradually declining, share. Other applications such as trauma and craniofacial repair remain stable.71

Market outlook: Market growth will be shaped by three trends: (1) approvals of bioactive and cell-based grafts, (2) adoption of 3D-printed and customizable scaffolds, and (3) demand for MIS-compatible delivery systems.74 Together with demographic factors and rising procedural volumes, these dynamics are expected to support sustained long-term market growth.75

Fda-approved bone graft products: The contemporary bone graft market is supported by an extensive range of FDA-cleared and approved products spanning allografts, synthetics, and biohybrids. These materials reflect diverse strategies for replicating or enhancing the regenerative environment of autologous bone.76–89 Within the allograft segment, Medtronic’s Grafton® DBM and DePuy Synthes’ DBX® have been widely adopted since their 510(k) clearance in 2005, offering osteoconductive scaffolds with preserved growth factor activity.76,77 Similarly, Zimmer Biomet’s Puros® DBM, regulated as an HCT/P tissue product, provides a fully demineralized cancellous bone matrix designed to retain natural remodeling potential.78

Synthetic scaffolds have also gained strong clinical traction. Stryker’s Vitoss® (β-TCP, cleared 2000) remains a standard in spine and trauma repair.79 Medtronic’s MasterGraft®, combining hydroxyapatite with β-TCP, and Baxter’s Actifuse®, a silicate-substituted calcium phosphate ceramic cleared in 2018, further exemplify the versatility of synthetic ceramics for resorption control and osteoconduction.80,81 NovaBone® Putty, cleared in 2002, pioneered the use of bioactive glass in a moldable format to stimulate cellular activity via ionic release.82

The biohybrid segment has marked a turning point for bone regeneration strategies.83 Medtronic’s INFUSE®, which delivers recombinant BMP-2 on a collagen sponge, was granted PMA approval in 2002 and established a benchmark

for osteoinductive products.98 Subsequent approvals have included Wright Medical’s Augment®, using rhPDGF-BB with β-TCP, and Cerapedics’ i-Factor®, incorporating a synthetic P-15 peptide, both approved in 2015.99,100 Cell-based allografts such as Orthofix’s Trinity ELITE®, NuVasive’s Osteocel®, and DePuy Synthes’ ViviGen® are regulated as HCT/P products and provide viable progenitor cells to directly support osteogenesis.86–88 Stryker’s BIO⁴®, launched in 2015, combines an allograft matrix with mesenchymal stem cells, osteoblasts, and angiogenic growth factors to maximize regenerative potential.89 A concise overview of these FDA-cleared and approved products, organized by graft class and regulatory pathway, is provided in Table 5.89

|

Company |

Product name |

Graft type |

Composition |

FDA status |

|

Medtronic |

Grafton® DBM |

Allograft (DBM) |

Demineralized human cortical bone matrix |

510(k), 2005 |

|

DePuy Synthes (MTF) |

DBX® |

Allograft (DBM) |

DBM + sodium hyaluronate carrier |

510(k), 2005 |

|

Zimmer Biomet |

Puros® DBM |

Allograft (DBM) |

Fully demineralized cancellous bone |

HCT/P tissue product |

|

Stryker |

Vitoss® |

Synthetic |

β-TCP, ~90% porosity |

510(k), 2000 |

|

Medtronic |

MasterGraft® |

Synthetic |

Biphasic HA/β-TCP |

510(k), mid-2000s |

|

Baxter (ApaTech) |

Actifuse®f |

Synthetic |

Silicate-substituted calcium phosphate |

510(k), 2018 |

|

NovaBone Products |

NovaBone® Putty |

Synthetic |

Bioactive glass in collagen matrix |

510(k), 2002 |

|

Medtronic |

INFUSE® |

Biohybrid (rhBMP-2) |

Collagen sponge + rhBMP-2 |

PMA, 2002 |

|

Wright Medical |

Augment® |

Biohybrid (rhPDGF) |

rhPDGF-BB + β-TCP granules |

PMA, 2015 |

|

Cerapedics |

i-Factor® |

Biohybrid (peptide) |

P-15 peptide on anorganic bone mineral |

PMA, 2015 |

|

Orthofix (MTF) |

Trinity ELITE® |

Biohybrid (Cellular Allograft) |

Cryopreserved allograft with viable MSCs |

HCT/P |

|

NuVasive |

Osteocel® |

Biohybrid (Cellular Allograft) |

Cancellous + DBM with MSCs |

HCT/P (~2008) |

|

DePuy Synthes |

ViviGen® |

Biohybrid (Cellular Allograft) |

DBM + osteoblast-lineage cells |

HCT/P (~2014) |

|

Stryker (Osiris) |

BIO⁴® |

Biohybrid (Cellular Allograft) |

Allograft matrix + viable cells and growth factors |

HCT/P (~2015) |

Table 5 Selected FDA-approved bone graft products by class and regulatory pathway.91-104 The table summarizes representative bone graft substitutes cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), organized by graft class and regulatory pathway.

Bone graft companies - key players: The global bone grafts and substitutes market is shaped by a core group of multinational corporations and specialized biomaterials firms, each advancing distinct product strategies.80–98 Medtronic is among the most influential players, with its INFUSE® Bone Graft recognized as the leading recombinant BMP-2–based therapy.80,83 In FY 2024, Medtronic reported revenues of USD 32.364 billion, with the INFUSE® platform alone estimated to generate approximately USD 700 million annually, underscoring its clinical and commercial importance.39,21,62

DePuy Synthes, part of Johnson & Johnson, continues to lead in the demineralized bone matrix category with DBX® Putty, a 510(k)-cleared product that combines osteoconductive scaffolding with retained osteoinductive proteins.90 Orthofix, in collaboration with MTF Biologics, provides Trinity Evolution®, a cellular allograft enriched with mesenchymal stem cells that delivers osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties in a single graft material.91

Stryker dominates the synthetic category with its long-standing β-TCP scaffold Vitoss®, which has seen broad adoption in spinal and trauma procedures.92 In 2024, Stryker reported USD 22.6 billion in total revenue, with Orthopaedics and Spine growing by 8.7% organically, reflecting expanding graft demand.16 NovaBone Products, a pioneer in bioactive glass grafts, has continued to expand the clinical reach of its NovaBone® Putty, particularly in dental and trauma indications.93

Baxter’s Actifuse® illustrates the osteostimulative approach to synthetic grafting, leveraging silicon doping to enhance bone formation.94 Geistlich Pharma, meanwhile, has established global dominance in the dental segment with Bio-Oss®, a bovine-derived xenograft supported by decades of clinical use.87 Zimmer Biomet adds to the hybrid market with its RegenOss® collagen-HA scaffold and reported USD 7.95 billion in revenue in 2024, with Q2 2025 sales alone exceeding USD 2.07 billion.2,10,23,96

Integra LifeSciences markets Accell Connexus®, a DBM-based putty, while Bioventus offers OsteoAMP®, an allograft enriched with endogenous growth factors that accelerates bone fusion.97,98 These companies reflect two parallel strategies: scalable synthetics for structural support and biologically enhanced hybrids that replicate autologous bone regeneration.80–98 Table 6 summarizes leading companies in the sector alongside representative commercial products spanning synthetic, allograft, and biohybrid approaches.80–98

|

Company |

Product name |

Graft type |

|

Medtronic |

INFUSE® |

rhBMP-2 / Growth factor |

|

DePuy Synthes |

DBX® Putty |

Demineralized Bone Matrix (DBM) |

|

Orthofix / MTF Biologics |

Trinity Evolution® |

Biohybrid (Allograft + Cells) |

|

NovaBone Products |

NovaBone® |

Synthetic (Bioactive Glass) |

|

Baxter (Apatech) |

Actifuse® |

Synthetic (Silicate-CaP) |

|

Geistlich Pharma |

Bio-Oss® |

Xenograft (Bovine) |

|

Zimmer Biomet |

RegenOss® |

Biohybrid (Collagen-HA Scaffold) |

|

Integra LifeSciences |

Accell Connexus® |

DBM Putty |

|

Bioventus |

OsteoAMP® |

Bioactive Allograft |

Table 6 Key companies in the bone grafts and substitutes market and representative commercial products.81-90 The table lists major companies active in the bone grafts and substitutes sector, their representative products, and the corresponding graft types.

When comparing revenues across the leading players, Medtronic holds the largest share with total revenues of USD 32.364 billion in 2024, supported by INFUSE® generating around USD 700 million annually.28,62,99 Stryker follows with USD 22.6 billion in revenue, buoyed by the strong growth of its Orthopaedics and Spine divisions.16 Zimmer Biomet reported more modest but steadily growing revenues of USD 7.67 billion in 2024, reflecting its continued position as a key orthopedic innovator.68 Together, these companies account for the majority of commercialized graft sales worldwide, anchoring a market that is increasingly moving toward hybrid, biologically enhanced solutions.80–98

The commercial development of bone grafts follows a structured workflow that includes sourcing of raw materials, scaffold fabrication, and downstream processing steps to ensure clinical safety and scalability.60 Each stage influences graft performance, with donor tissue prep, material selection, and sterilization shaping clinical integration and regulatory approval.61 Figures 3 and 4 provide an overview of the manufacturing pipeline, which is divided into pre-manufacturing, manufacturing, and post-manufacturing stages.62

Unlike autologous grafting, which depends on intraoperative harvesting, engineered grafts require upstream preparation of source materials such as cadaveric bone, ceramic powders, or polymer composites, followed by standardized downstream processing to achieve sterility and reproducibility.63 These steps are particularly critical for biohybrid grafts that integrate scaffolds with bioactive signals.64

Pre-bioprinting

Raw material sourcing & processing: Bone graft inputs are derived from several sources including allograft bone, synthetic ceramics such as hydroxyapatite (HA) and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), and biodegradable polymers.75 Allograft tissue requires careful donor screening and processing, often involving demineralization to remove antigenic components while retaining osteoinductive proteins in demineralized bone matrix (DBM).73 Synthetic grafts are produced by powder synthesis and sintering, creating ceramics with controlled porosity and degradation.47 Polymers such as polylactic acid or collagen derivatives are processed using methods like lyophilization or extrusion to yield scaffolds that can be used directly or blended into composites.65 These categories of raw materials form the basis for the comparative overview presented in Table 7, which summarizes the properties of leading scaffold compositions.41

|

Material class |

Key attributes |

Representative products |

Reference |

|

Allograft/DBM |

Retains native growth factors, osteoconductive matrix |

Grafton®, DBX® |

71 |

|

Ceramics (HA, β-TCP) |

High compressive strength, tunable resorption |

Vitoss®, Actifuse® |

67 |

|

Polymers (PLA, PGA) |

Flexible, moldable, customizable degradation kinetics |

OsteoSet®, Collagraft® |

50 |

|

Polymer–ceramic composites |

Combine strength with controlled resorption and bioactivity |

Collagraft®, NexOss® |

70 |

|

Cell-based constructs |

Scaffold seeded with MSCs, provides osteogenesis |

Trinity Evolution®, Osteocel® |

75 |

Table 7 Representative classes of raw materials and composites for bone grafts and their key attributes50,67,70,71,75 The table outlines principal material categories used in bone graft substitutes, including allograft/DBM, ceramics, polymers, polymer–ceramic composites, and cell-based constructs, along with their defining features and representative commercial products.

Cell/donor tissue preparation: In grafts incorporating viable cells or donor-derived tissue, upstream preparation is essential to preserve bioactivity while minimizing immunogenicity.73 Cadaveric bone is decellularized, demineralized, and cryopreserved to remove antigenicity while preserving collagen and osteoinductive proteins.52 This processing allows the creation of demineralized bone matrix (DBM), which maintains endogenous growth factors such as BMPs that support host cell recruitment and vascularization.53 For cell-based grafts, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue are often expanded ex vivo and seeded onto scaffolds to enhance osteogenesis.41 Stem cell–augmented grafts, such as Trinity Evolution® or Osteocel®, exemplify this strategy by combining an osteoconductive scaffold with viable progenitor cells to accelerate bone formation in critical-sized defects.54 These workflows show how cell sourcing and donor processing define the regenerative potential of biohybrid grafts.55

composite/biomaterial selection: The selection of biomaterials represents a pivotal pre-manufacturing step that determines both mechanical stability and biological integration of the graft.42 Synthetic ceramics such as hydroxyapatite (HA), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), and biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP) are widely used for their osteoconductivity, tunable degradation, and compressive strength.47 Biodegradable polymers including polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), and collagen are employed to enhance flexibility, porosity, and handling characteristics.59 Ceramic–polymer composites combine ceramic strength with polymer resorbability and conformability.50 These hybrid constructs aim to balance structural support with bioactivity, making them particularly useful in poorly vascularized or irregularly shaped defects.80 Table 7 summarizes the principal classes of raw materials and composite formulations used in bone graft manufacturing, along with their key features and representative applications.41

Manufacturing techniques: Manufacturing techniques aim to produce scaffolds with the required integrity, porosity, and bioactivity.42 The choice of technique depends on the source material, whether donor-derived, ceramic, polymeric, or composite, and influences scalability, regulatory compliance, and market adoption.43 Table 8 illustrates the overall relationship between these manufacturing techniques and the final properties of bone grafts.67

|

Technique |

Primary materials |

Key outcomes |

Representative products |

Reference |

|

Demineralization |

Allograft bone |

Retains growth factors, reduced immunogenicity |

Grafton®, DBX® |

71

|

|

Decellularization |

Allograft bone |

Removes donor cells, preserves ECM |

Regenafil®, Puros® |

73

|

|

Ceramic sintering |

HA, β-TCP, BCP |

Tunable porosity and resorption |

Vitoss®, Actifuse® |

67

|

|

Polymer processing |

PLA, PGA, collagen |

Flexible, moldable scaffolds |

OsteoSet®, Collagraft® |

50

|

|

Additive manufacturing |

Ceramics, composites |

Anatomically tailored, high precision |

NexOss®, 3D-printed HA |

78 |

Table 8 Overview of manufacturing techniques for bone grafts and their primary outcomes 50,67,71,73,78 The table summarizes major manufacturing approaches for bone grafts, including demineralization, decellularization, ceramic sintering, polymer processing, and additive manufacturing, along with their key materials, outcomes, and representative commercial products.

Demineralization and decellularization: Demineralization is primarily applied to allograft bone to create demineralized bone matrix (DBM), a material that retains osteoinductive growth factors such as BMPs while reducing immunogenicity.73 Acid extraction removes mineral content while preserving collagen and signaling proteins needed for osteogenesis.76 Decellularization processes further eliminate donor cells, lowering the risk of immune rejection and disease transmission while maintaining structural proteins that support host cell infiltration.53 These processes are central to commercial DBM products such as Grafton® and DBX®.41

Ceramic sintering: Synthetic bone grafts composed of hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate, or biphasic calcium phosphate are typically manufactured through sintering of ceramic powders.47 Sintering consolidates ceramic powders at high temperature, producing scaffolds with tunable porosity and strength matched to cortical or cancellous bone.48 Adjustments in sintering temperature and particle size enable control over degradation rates, allowing grafts to resorb synchronously with new bone formation.49 These materials form the basis of commercial products such as Vitoss® and Actifuse®.50

|

Method |

Scalability potential |

Regulatory complexity |

Clinical adoption trends |

Reference |

|

Demineralization |

Moderate |

Well established |

Widely used in spine and trauma |

74 |

|

Decellularization |

Moderate |

Medium |

Growing use in allografts |

73 |

|

Ceramic sintering |

High |

Low |

Strong adoption in synthetic grafts |

69

|

|

Polymer processing |

High |

Medium |

Expanding use in composites |

50 |

|

Additive manufacturing |

Emerging |

High |

Rapid growth in custom grafts |

79 |

|

Polymer processing |

High |

Medium |

Expanding use in composites |

79 |

Table 9 Comparative analysis of manufacturing methods by scalability and clinical translation.50,67,71,73,78 The table compares principal bone graft manufacturing methods in terms of production scalability, regulatory readiness, and clinical translation potential, outlining their advantages and limitations.

|

Process area |

Methods/standards |

Application by graft type |

Regulatory considerations |

Reference |

|

Sterilization |

Gamma irradiation, ethylene oxide, supercritical CO₂ |

Allograft, DBM, synthetics |

Must retain bioactivity |

74 |

|

Quality control |

Mechanical strength testing, porosity measurement, growth factor assays |

Medium |

Growing use in allografts |

86 |

|

Ceramic sintering |

High |

All graft types |

FDA GMP, ISO 13485 |

87 |

|

Packaging |

Cryopreservation, lyophilization, vacuum sealing |

Cell-based, DBM, synthetics |

Shelf-life and sterility |

90 |

|

Regulatory compliance |

FDA 510(k), CE Mark, PMDA approval |

Varies by product (synthetic vs biohybrid) |

Higher scrutiny for biohybrids |

91 |

Table 10 Post-manufacturing processes for bone grafts: sterilization, quality control, and regulatory frameworks.74,86,87,90,91 The table outlines key post-manufacturing steps for bone grafts, including sterilization, quality control, ceramic sintering, packaging, and regulatory compliance, with their associated methods, graft type applications, and governing standards.

Polymer processing: Biodegradable polymers such as PLA and PGA are processed through techniques including extrusion, lyophilization, and solvent casting to generate porous scaffolds with customizable shapes.65 Lyophilization controls pore size and interconnectivity, supporting vascular ingrowth and nutrient diffusion.54 Solvent casting combined with particulate leaching is often used to produce uniform porosity, enhancing osteoconductivity when blended with ceramics.55 Polymer scaffolds are frequently used as carriers for growth factors or stem cells, providing both structural support and biological augmentation.70

Additive and hybrid manufacturing: Advances in additive manufacturing enable the precise fabrication of scaffolds with tailored architecture and mechanical properties.57 Three-dimensional printing of calcium phosphate or polymer-ceramic composites allows the creation of anatomically specific grafts that conform to complex defect geometries.72 Hybrid approaches combine 3D printing with traditional methods to yield injectable or moldable constructs that balance handling ease with reinforcement.68 These techniques are increasingly aligned with the demand for minimally invasive, surgeon-friendly solutions.59

Post-manufacturing: Post-manufacturing processes ensure that bone grafts are sterile, consistent, and compliant with regulatory standards before entering clinical use.90 These steps safeguard patient safety and influence shelf-life, handling, and scalability.91 Figure 6 provides an overview of how downstream processes align with regional regulatory frameworks in the United States, Europe, and Asia-Pacific.92

Figure 6 Regional distribution of the global bone grafts and substitutes market (2023).62

The image shows global market share by region.35 North America leads, followed by Europe and Asia‑Pacific, while Latin America and the Middle East & Africa remain emerging markets.62

Sterilization and quality control: Sterilization is essential to eliminate microbial contamination while preserving the biological and structural integrity of graft materials.93 For allografts, common sterilization techniques include gamma irradiation, ethylene oxide treatment, and supercritical carbon dioxide processing, each balancing microbial safety with retention of osteoinductive proteins.94 Quality control assesses strength, porosity, and bioactivity to ensure batch reproducibility.95 For biohybrid grafts containing growth factors or viable cells, additional release testing is required to confirm factor stability and cell viability.96

Packaging and regulatory compliance: Packaging strategies are designed to maintain sterility and extend shelf-life without compromising handling properties.97 Cryopreservation systems are frequently required for viable cell-based products, while lyophilized or pre-hydrated packaging formats are common for synthetic and DBM grafts.98 Regulatory compliance follows frameworks such as FDA 510(k), CE marking, and PMDA approval.80 These regulatory processes evaluate safety, efficacy, and quality, with bioactive and cell-based grafts often facing heightened scrutiny compared to purely synthetic products.77 Table 6 summarizes the principal regulatory considerations and packaging approaches associated with each graft class.78

Clinical evaluation of bone graft substitutes: Advances in scaffold design, biomaterial chemistry, and biological augmentation have accelerated translation into clinical and preclinical testing (Figure 7).101 Strategies focus on enhancing osteointegration, stimulating angiogenesis, and enabling site-specific regeneration through growth factors, peptides, ECMs, and engineered cells.101

Figure 7 Pipeline bone graft technologies by type and stage.105

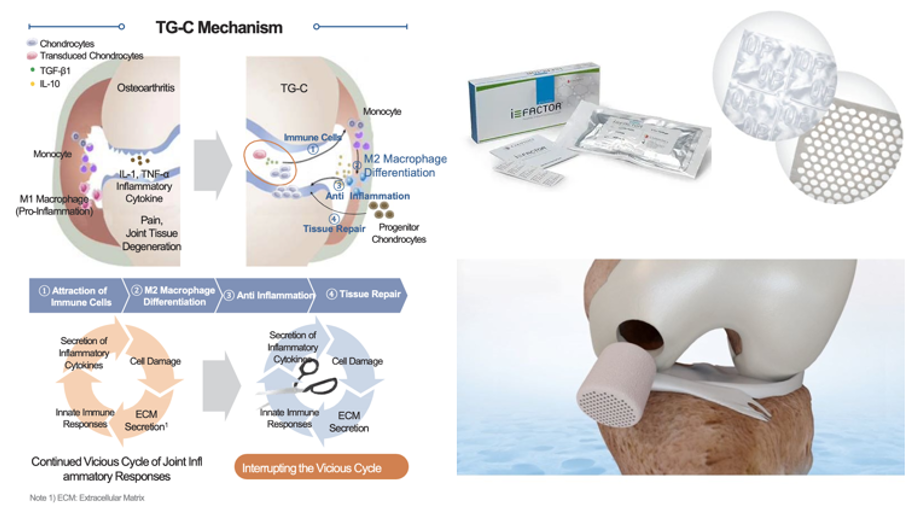

The image shows representative clinical and preclinical graft platforms, including peptide‑based grafts (P‑15L), growth factor–enhanced scaffolds (EPIFIX®), bioinspired osteochondral implants (Agili‑C™), MSC‑seeded ceramic scaffolds, and gene‑enhanced constructs such as TissueGene‑C.105

Growth factor–enhanced scaffolds: NOVOGEN (Kuros Biosciences) is a synthetic scaffold integrated with rhBMP-2 optimized for lower dosing, maintaining osteoinductive efficacy while reducing risks of ectopic ossification and inflammation.102

Peptide-enhanced grafts: P-15L Bone Graft (Cerapedics) employs a collagen-mimetic peptide bound to an anorganic bone mineral scaffold to promote adhesion and osteogenesis. It is in Phase III FDA IDE trials for cervical and lumbar fusion.103

Bioinspired osteochondral implants: Agili-C™ (CartiHeal) is an aragonite-based implant designed for cartilage and subchondral bone repair. Already CE-marked and under FDA IDE review, it enables one-step repair without staged grafting.104

Ecm-derived injectables: EPIFIX® Injectable (MiMedx) is an amniotic ECM putty formulated for minimally invasive delivery. In Phase I/II evaluation, it permits injection into irregular bone voids and demonstrates angiogenic and immunomodulatory activity for trauma indications.105

Composite scaffolds: SmartBone® (Industrie Biomediche Insubri) combines bovine-derived mineral matrix, bioresorbable polymers, and collagen fragments to provide stability with tunable elasticity. CE-approved in Europe, it is under FDA IDE review for craniofacial, dental, and trauma indications.106

Msc-seeded constructs: At the preclinical stage, MSC-loaded biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP) scaffolds developed by the University of Michigan couple 3D-printed ceramics with autologous MSCs to support vascularized regeneration in long bone defects.107

Gene-enhanced platforms: TissueGene-C (Kolon TissueGene) combines allogeneic chondrocytes with TGF-β1 for osteoarthritis repair. In Phase III trials in Asia, it promotes immune cell recruitment, M2 macrophage polarization, and coupled cartilage–bone remodeling.108

Summary and outlook: Figures 6&7 compare innovation strategies, material bases, and clinical outcomes across platforms.108 Collectively, they reflect a shift toward multiphasic, bioactive scaffolds uniting mechanical strength with biological function.101 Remaining barriers include regulatory reproducibility, long-term safety, and cost-effectiveness, which continue to limit widespread adoption.101

Critical-sized bone defects (CSDs) remain a major challenge in orthopedic surgery, with current strategies still dependent on autografts despite their limitations in donor-site morbidity, availability, and surgical complexity.101 Biohybrid grafts, synthetic or composite scaffolds enhanced with biologics such as peptides, growth factors, or viable cells, offer a path to achieving osteoconduction, osteoinduction, and osteogenesis.102

Clinical platforms including NOVOGEN, P-15L, Agili-C™, EPIFIX®, SmartBone®, MSC-loaded ceramics, and TissueGene-C demonstrate the potential of biohybrids to address diverse orthopedic needs.103 Yet translation is constrained by reproducibility, long-term safety, and cost-effectiveness, highlighting the need to balance bioactivity with regulatory compliance.104

Future strategies will likely focus on multiphasic scaffolds that unite structural stability with tailored biological signaling, adaptable to both load-bearing and non-load-bearing sites.105 Emerging directions include personalized 3D-printed ceramics with autologous stem cells, recombinant peptide- or protein-based constructs for controlled bioactivity, and injectable bioactive pastes for minimally invasive repair.106

Advances in immunomodulation, vascularization, and controlled release of signaling molecules are expected to improve integration and reduce complications such as ectopic ossification or chronic inflammation.107 At a systems level, scalable off-the-shelf biohybrids and patient-specific grafts will increasingly converge with digital surgical planning, advancing personalized regenerative orthopedics.108

Ultimately, the next decade of biohybrid innovation will hinge on integrating material science, biology, and clinical translation to produce reproducible, safe, and economically viable solutions for CSD repair.108

There is no funding to report for this study.

Asher Kim expresses appreciation to Professor Bill Tawil for overseeing the framework of this review, and for the insightful lectures and advice concerning biomaterials and tissue engineering, which contributed to the development of this paper.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Kim,, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.