Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6445

Review Article Volume 15 Issue 3

1Professor, Psychoanalysis Department of Psychology Institute, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2Professor, Researcher at CNPq and Pro Scientist of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

3Doctor, Post-Graduate Program in Psychoanalysis of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

4Postdoctoral in Statistics and Visitor Researcher of University of Regensburg, Germany

5Doctor student, under the supervision of Professor Luciana Ribeiro Marques, at the Post-Graduate Program in Psychoanalysis of the State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Correspondence: Luciana Ribeiro Marques, Professor, Psychoanalysis Department of Psychology, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Tel +55 (21) 99965-7729

Received: June 02, 2024 | Published: June 27, 2024

Citation: Marques LR, Alberti S, da Silva HF, et al. Challenges and paradoxes in mental health care for transgender people in Brazil: a review of historical contexts and narratives. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry. 2024;15(3):203-209. DOI: 10.15406/jpcpy.2024.15.00782

Individualized interviews with transgender people reveal diverse experiences, offering unique data for mental health care providers. These narratives challenge psychopathological categories and highlight the need for deeper investigation. The study aims to address these experiences comprehensively, understand the importance of each transgender narrative, and counteract biased approaches. Understanding the historical context of transgender assistance in Brazil is crucial. This context reveals a paradox: the need for individualized listening versus the standardization of transgender individuals under "conditions related to sexual health" in ICD-11. Brazil leads in transgender murders. Violence against this population stems from prejudices, ignorance, and pathologization, as historical evidence shows. We consider it essential to investigate these causes further and contribute by listening to this population, revealing the diversity in their experiences. A literature review of articles from 2011 to 2021 in Brazil identified 29 publications on transgender issues and psychology. This qualitative research used refined scales to address diverse transgender experiences, reducing result generalization. The historicization of the problems faced by transgender people in Brazil and the verification of the particularities revealed in the narrative of each participant are necessary counterpoints to the segregation and critical situation of this population in the country. By synthesizing individualized narratives, historical context, and literature, this study contributes to improving mental health care and social support for transgender individuals, emphasizing the importance of individualized listening and culturally sensitive approaches to reduce stigmatization and promote depathologization.

Keywords: psychology, transgender, literature review, individual interviews

SAT, Surface Air Temperature; SSS, Sea Surface Salinity; SST, Sea surface temperature; RH, Relative Humidity; DO, Dissolved Oxygen; BOB, Bay of Bengal; IO, Indian Ocean

Individualized treatment interviews with transgender people highlight the plurality of situations experienced by the participants and present them uniquely to the mental health care provider. The narratives not only contrast with the psychopathological categories found in the specialized literature but also point out the necessity to deepen the investigation of such experiences. The study aims better to address the phenomenon, understand what is at stake in each transgender narrative, and, in addition, definitely counter-biased and pathologizing approaches. Currently, in Brazil, there are many interventions conducted with transgender participants. Particularly in medicine and psychology, given that these are the areas transgender people seek the most to help them in their gender affirmation. For example, we can point out the work carried out since 2014 by the Gender Identity Program (PROTIG) of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA). The project aimed to assist transgender youth seeking gender-affirmative treatment and offered at a public health-care service specialized in gender in southern Brazil.1 The (PROTIG) program, which aims at a global listening of the transgender person, is not restricted to medical and physical interventions for gender affirmation, but to the promotion of mental health and general emotional well-being, as they found that the practice with transgender people: "[...] challenges health teams to develop care protocols that focus on singular interventions that cover the different social structures that make up the individual's environment, as well as specific and appropriate interventions for each situation regarding the demand for medical treatment of gender affirmation and social transition […] focusing on the promotion of mental health, general emotional well-being, and recognition of legal and social rights in different spheres of the environment and not only medical procedures and physical interventions of gender affirmation".1 A quick historical overview seems crucial to understand the issue of assistance to transgender people in the country, mainly because it can clarify a particular paradox: on the one hand, the necessary individualized listening, which demands that we respect the maxim according to which each case is singular; on the other hand, the inclusion of transgender people in the category of “conditions related to sexual health”, due to the classification of “gender incongruence”, according to ICD-11,2,3 which is still a form of standardization. Listening without prejudice is fundamental to receive transgender people and relieve their suffering.

The literature review examined scientific articles published from 2011 through 2021 in Brazil. Twenty-nine publications representing two main study categories were eligible: transgender and psychology. The qualitative part of this research uses refined scales for the treatment of cross-sectional data. Reducing the generalization of results was necessary to address the diversity of life experiences of transgender participants.4 As we understand that there is no listening to life experience outside of a debate that considers the culture, narratives and practices that occur in a given society, we believe it is fundamental to be able to contextualize the data historically. This study aims to contribute to the efforts being mobilized by different areas of society, particularly those that are part of the context of psychology in the country. The dire situation of this population, the most threatened according to world statistics,5 shows that Brazil is the country with the highest rate of violence followed by the death of transgender people in the world.6 We raised the hypothesis that, in part, this statistic stems from ignorance and prior categorizations leading to the segregation of this population by cisgender people in a context that fits into Goffman's concept of stigmatization.6 As Rosa et al. point out,7 throughout the twentieth century, Brazilian society pathologized the transgender person, which “persists today”.7 The whole situation counters the guidance of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,8 which warns that, in reality, inexperienced doctors are those who “can confuse signs of gender dysphoria with delusions”.8 Of course, the vast majority of those who present a gender dysphoria “are not suffering from an underlying serious psychiatric disease”.8

History of the issue in the country

In a report by BBC News Brasil, “’Monster, prostitute, faggot’: how Justice condemned Brazil's 1st sex change surgery”, journalist Amanda Rossi et al.9 reveals how access to health care for the transgender population was judicialized by medicine and the pioneering spirit of a doctor, Roberto Farina, who carried out the first genital gender affirmation surgery (GAS), in 1971. The surgery went well until, in 1976, the Public Prosecutor's Office of the State of São Paulo discovered the medical intervention and denounced Dr. Farina for severe body injury, subject to 2 to 8 years in prison. The complaint highlighted that: "there is not and cannot be any sex reassignment with these operations. What is achieved is the creation of stylized eunuchs, for the better pleasure of their deplorable sexual perversions and, also, of the lecherous who are satisfied in them. Such individuals, therefore, are not transformed into women, but into true monsters (complaint by prosecutor Luiz de Mello Kujawski in a request for a police investigation)".9 Even after the testimony of Dr. Farina's patient, the doctor was convicted by the trial court, having been acquitted only 1 year later: "My life before the surgery was an unbearable martyrdom for having to carry a genitalia that never belonged to me. After the surgery I was free - thanks to God and Dr. Roberto Farina – of the excruciating organs that made my life into hell, and I felt so relieved that I seemed to have created new wings for life".9

The belief in the immutability of sex persisted in many medical opinions even in the early 1990s, twenty years after the first sex reassignment surgery. But, little by little, with the repercussion in the media, which Leite Junior et al.10 called the “Roberta Close phenomenon” – an extremely popular transgender female in television programs who had her surgery abroad –, the debate began within the Federal Council of Medicine (CFM),11-14 which resulted in the Proposal for a Resolution that authorized the surgery on an experimental basis. Through this proposal, the CFM claims to the medical power the competence to offer “to society an ethical proposal that reconciles the plastic possibility and the legal impediments that prohibit the mutilation of the human being, seen as the simple suppression of an organ or functions”.11 Far from becoming a consensus, the attempt to transform transgender into a mental health problem reveals the aim to justify its medicalization, limiting it to the power of medicine. Therefore, the fundamental ethical issue for CFM as an advanced sector of the medical society and a guardian of the social interests of medicine was to define the genital GAS and the other secondary sex characteristics as treatment, aiming to recompose the biopsychomorphological unit of the human being, far above the simple reproductive function. The Resolution was revoked and replaced by the CFM Resolution No. 1,652/2002, which kept the definition of criteria for the diagnosis of “transgender” but removed the experimental character of neocolpovulvoplasty surgery in 2002.12 Subsequently, the procedures of interdisciplinary care were standardized through the GM/MS Ordinance No. 1,70715 and No. 457,16 which established technical and ethical guidelines for the "Transsexualization Process" in the Unified Health System (SUS) in Brazil,15,16 an institutionalization of care. By defining the National Guidelines for gender affirmation, aiming to guarantee the use of the social name, hormonal therapy, and access to GAS, the SUS aimed to respond, as early as 2008, to “harms resulting from stigma, discriminatory processes and exclusion that violate human rights”.15,16 Hormonal therapy and GAS were legally offered in our country perhaps late, considering that in Brazil, and especially in the world, transitions (gender affirmation) were already occurring a few years ago.13,17

Secretly, the surgeries began to be performed initially only on transgender females. Six years later, the first transgender male had his surgery comprising: mastectomy, hysterectomy, and removal of the ovaries. João Nery was one of the great defenders of the cause of transgender people in the country, and due to his militancy as a psychologist and a politician, the Gender Identity Bill – not yet voted on in the National Congress – was named after him. His books, including Viagem Solitária [Lonely Journey],18 numerous interviews, university conferences and media participation, were significant in introducing and disseminating information on the particularities of transgender issues to part of the Brazilian population. Even today in Brazil, the genital GAS in transgender male is rare due to the complexity of the surgical technique known to only a few, the reason why it is just allowed on an experimental basis in university hospitals, such as, for example, at the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of the State University of Rio de Janeiro.19, 20 However, it is essential to praise the initiative of the SUS – through a comprehensive public monitoring – that aims to reduce the suffering of transgender people in the face of the dysphoria experienced in their bodies.24–34

Since 2008, we have followed years of changes in the perception of the transgender phenomenon by medical sciences through the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems – ICD – and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM – which the regulations of both the SUS and the CFM began to monitor. As Galli et al.21 medical-scientific discourses "make us frame the transgender person [...] this reductive frame ends up taking the form of a polyhedron, due to the variety and diversity",when we look at the speeches of transgender people themselves.36–45

Survey of the trans issue in academic production in Brazil

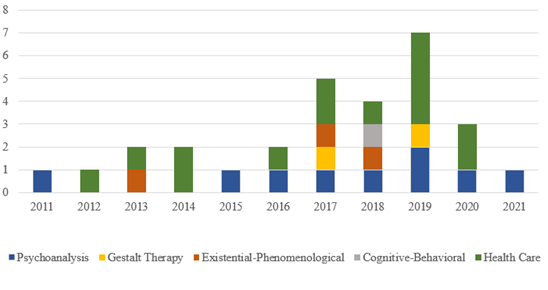

In order to verify to what extent the trans issue was being worked on or not, we selected twenty-nine scientific articles published from 2011 to 2021 representing transgender and psychology categories. Each article was analyzed by four topics: 1. Publication year, 2. Theoretical-conceptual approaches in psychology, 3. Main topics – Literature review, Historical contextualization, Depathologization, Individual interview and Public health policies aimed at transgender people –, and 4. The presence of individual interview analysis. Among the theoretical-conceptual approaches in psychology published in the country in the last years on transgender people, was highlighted: Psychoanalysis, Gestalt Therapy, Existential Phenomenological, Cognitive-Behavioral and Health Care approaches. We emphasize that the Health Care approach includes: Interviews in Social and Community Psychology, Group Psychotherapy and Psychology Applied to Mental Health, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Theoretical-conceptual approaches in psychology, published per year, which discuss transgender people

The evaluation of the literature on the main topics addressed in the eligible publications in this research shows that 100% of the articles were literature reviews, and 70% contemplated the historical contextualization of transgender people in Brazil. Regarding the approach to the depathologization of transgender people, 55% of the articles mentioned debates held in the country. Regarding individual interviews with transgender people in Brazil, although we found that 100% of the articles point to this qualitative method, only 31% of them had data analysis. Finally, concerning public health policies, we found that 31% of the articles addressed the theme as a valuable tool regarding health care.

Until 2010, very few texts were published on transgender people and psychology in the country. We cannot fail to mention the work of Arán,22–27 a psychoanalyst who engaged in the construction of public policies to access health for the transgender population and even had his theoretical and political conceptions marked in the texts of the Ordinances of the Ministry of Health in which he actively participated. Ceccarelli et al.28 was another pioneer mentioned in several articles. Finally, there is Berenice Bento et al,29,30 sociology professor who has worked a lot in articulation with psychology.

Individual semi-structured interviews. Thirteen interviews were described based on four repeated topics detected in their narratives[1]. These topics are: 1. Social name – maintained radical, own name, suggestions random name –, 2. Genital GAS – underwent, wish, do not want –, 3. Sexual orientation – hetero, homo, regardless of gender–, and 4. Information on gender affirmation. An exploratory analysis based on relative frequencies was implemented. The complete raw data related to the articles and interviews are available in the supplementary material.

We collected the material during the interviews with four transgender females and nine transgender males. To guide the reading, we decided to identify the four transgender females as participants 1 to 4 and, subsequently, the nine transgender males as participants 5 to 13. To analyze the participants' narratives, we used refined scales to treat cross-sectional data to reduce the generalization of results,4 a necessary method to address the diversity of life experiences of transgender people in Brazil. In this condition, the knowledge we can gain from the participants' narratives "is directed to the individual and the private [...], from a direct and detailed observation".31 The semi-structured interviews gave transgender persons a place to speak.

[1]Research authorized by the National Research Ethics Commission (CONEP), fulfilling the requirements of Resolution CNS 466/12 and its complementary ones, as well as the authorization of each of them, in writing, that they would be part of the research.

Interviews with transgender participants during gender affirmation, aiming at confidentiality, will be listed here from 1 to 13, with participants from 1 to 4 referring to transgender females and from 5 to 13 to transgender males. All participants identified themselves as transgender when they started the interviews, having even started the hormonal treatment at least 1 year ago. Among the topics addressed, we identified four of greater relevance: 1. Social name, 2. Gender affirmation surgery (GAS), 3. Sexual orientation, and 4. Information on gender affirmation.57–67

Social name

In Brazil, a change of name implied legal actions until 2018. Under the legislature, this change was only allowed to transgender people who had performed the genital GAS. To “guarantee the right to change the name regardless of surgical interventions”,32-34 it was necessary to enter the Federal Supreme Court (STF) with a certificate of Gender Identity Disorders (F64 of ICD-10 | OMS, 1993).35 In 2017, the first transgender lawyer Gisele Alessandra Schmidt e Silva, was a spokesperson for the struggle for this right: “Denying a person the right to have a name, to express their identity, is denying their right to exist. Your Honors are required not to deny us this right”.33,36

On March 1, 2018, based on STF's decision – restated from a provision provided for by the National Council of Justice37 – the Gender Identity Disorders (F64 of ICD-10 | OMS, 1993) certificate became optional concerning the change of name and gender in the civil registration of transgender people: "New forms of recognition have appeared in policies for the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in education institutions and public and private organizations, as well as in the cultural industry. Such news illustrates the recent gains in the political struggle by transvestites, transsexual and transgender people in Brazil, who nonetheless still experience a reality of extreme marginalization and social exclusion".20

Analysis of data extracted from the narratives of the transgender participants about the choice of the social name has pointed to a pretty systematic derivation of the name given at birth. For example, change can be followed by Morphology, which is the area of grammar that studies words in isolation, the structure and formation of words, and their inflections. Fundamentally a word has a stem, then desinences and affixes. In Portuguese, for example, ferro (iron), ferreiro (blacksmith), "ferr" is the root (ferro), "o" in "ferro" is the desinence (ferro), and in "ferreiro", "eiro" is an affix that allows the creation of a new word (ferreiro). It is precisely this construction that guides, in the narratives in question, the choice of names. Joana becomes João – a change in desinence – and observes: "I think the fundamental need is the recognition of a name. Without a name that represents us, we do not exist. We are completely invisible, abominable, objects in society",33 João Nery once said. The judgment of existing is the first thing a human needs, indeed starting with the name. Likewise, Rafael also becomes Rafaelly Wiest, a politician in the country’s south. However, it is by affixation that Lineu became Aline, for example. Regardless of changing the desinence or the affix, what calls our attention is that the name's root remains. All participants in this research's use of the social name show the importance that transgender people give to name change. Of the 13 participants, 11 maintained the radical of the given name at birth, 10 made their own choices of their social name, two accepted suggestions from family and close friends, and only one reported having chosen their social name randomly. It is important to emphasize that, even in the case of random choice, all social names reveal some relationship with the participant's intimate life story. As an example, we highlight the narrative of participant 13: :My mother gave me a German name [it was spelled with Y], which she thinks is German, right? I kept the Y. After all, I always liked Y. When I was a kid, I was bullied at school because I was always kind of masculine, so people kept calling me [name] like it was an insult. Then, everybody started calling me that, and I liked it and decided to use it”. Participant 5, in turn, put together parts of the names of the grandmother and mother to find his new name, while participant 11 chose to use the name chosen by the parents if they had a baby boy.

Genital gender affirmation surgery

Concerning one's own body dysphoria appears in 100% of the participants interviewed, either directly or indirectly. However, not all participants consider relevance to genital GAS. We observed that in Brazil, transgender people themselves still present the expression "I was born in the wrong body" in their narratives, which in other countries is no longer usual. Indeed, this way of expressing themselves reflects the tremendous stigma that transgender people still suffer insofar as this narrative would point to the existence of a "correct" body. As for the need for genital GAS, among our interviewees, some stated that the surgery is "[...] something you need" (e.g., Participant 3) and those for whom "[...] the genital was never a problem", which is why this participant, number 11, only did the chest GAS. Although the statements of these 2 participants diverge concerning genital GAS, they perfectly illustrate what Preciado postulates regarding the importance of the materiality of the bodies about gender: "It is purely built and, at the same time, entirely organic",38 as we can also observe in the narrative of patient P, referred to in the article entitled "Tornar-se homem, tornar-se mulher, relato de um caso" [Becoming a man, becoming a woman, a case report].31 In adolescence, P wanted to perform genital GAS but gave up, seeking other means for gender affirmation. This patient identified himself as a transgender person and resorted exclusively to hormonal therapy because of being afraid of surgery".31 Limits imposed on the possibilities of interventions in the body and the fact that genital GAS in cases of transgender males is still experimental in Brazil opens fissures regarding the possibility of gender affirmation. They may find other resources for gender affirmation (Figure 2). Among the four transgender females interviewed, one underwent genital GAS, two wished to undergo it, and one did not wish to do so. In contrast, among the nine transgender males, only one wishes to perform the genital GAS. A fact that we consider relevant refers to the prevalence of chest GAS among transgender males. All participants who were transgender males claimed to have performed chest GAS or the desire to undergo this surgery. The speech of participant 8, who is still waiting for chest GAS, illustrates well the data indicated: “Only my breasts are unwanted.” Another equally important fact concerns hormonal therapy as part of the intervention process in the body since 100% of the participants interviewed started gender affirmation using this resource.

Sexual orientation

Considering the narratives of the participants of this research, it is evident that the issue of sexual orientation should be discussed from a different perspective of gender identity. Gender identity and sexual orientation are heterogenic fields (cf. p. ex., APA, 2015, p. 835),39 and we found no necessary binarism regarding sexual orientation between the participants, as we can illustrate with the fragments extracted from their narratives:

"I will not say if I am straight or homosexual. I like people regardless of gender" (participant 6).

"I can relate to anyone, regardless of gender. I am pansexual" (participant 9).

"My girlfriend is a cross-dresser" (participant 11).

"I go out with boys and girls. I consider myself bisexual" (participant 12).

Figure 3 Sexual orientation rooted in dichotomous notions of sex and gender ends up labeling and reducing the transgender experience to cisnormative and heteronormative terms40 that disregard the particularities of each case. We took sexual orientations from our interviewee into account with the intent to testify to the plurality that overthrows norm. 3 declare themselves homosexuals, 3 heterosexuals, and 7 say the gender of their partners is not what matters for them.

Information on gender affirmation

Culturally shared experiences produce relationships between the media and the construction of identity. "Identity feelings derive from a performative construction marked by impermanence and incompleteness that transform the modes of self-perception in symbolic exchanges of the cultural fabric".41 Although the media gives us access to different guidelines on sexual diversity with soap operas, reports, and broadcasting of gay parades and films, Nascimento notes the lack of more in-depth media coverage on the subject. In turn, social media, as a new media modality, have increasingly become platforms open to autobiographical narratives, increasing the visibility of the transgender condition. Digital influence gains prominence, leading to an increasingly expanded sharing of personal experiences and criticisms related to sexual norms, which helps to reduce stigmas while supporting the identity struggle.42 This observation reflects Goffman's theory of stigma, considering stigma as an instrument of social segregation by transforming these stigmas into normative expectations. In his "Preliminary notions on the stigma," we read: Society establishes the means of categorizing persons and the complement of attributes felt to be ordinary and natural for members of each of these categories. Social settings establish the categories of persons likely to be encountered there.We identified the references that we could find in the reports of each of the 13 participants about how they believed they could find information that was effective in helping each one in their gender affirmation. Although the media, television, cinema, and the internet have played a vital role in identity construction, this research's relevant data indicates the surprising contribution of participants with family and friends. The gender affirmation occurred after conversations and research with the family nucleus, close friends, or other transgender people.

Information on gender affirmation

In most participants, Figure 4 we observe the contribution from several sources, as graph 7 points out and the narrative of participant 4 exemplifies:

“I always felt different from everything, but I didn't understand what it was. When my friend, who is also trans, explained to me what transgender was, because until then, I did not even know it existed, I realized that I fit into that category. Then I started searching the internet and told my mother I was trans. After that, my mother started researching with me and remembered that, since I was a child, playing with dolls, changing doll clothes, and playing with house things, I really fited into the term transgender person".

With the help of her friend, the internet, and finally, her mother, she could self-declare her gender identity as a transgender female. A recognition that, although transgender people experience signs in their body, affirmation is not done without culture, affective bonds, and peers.

Facing the historical problems transgender people experience in Brazil, of violence, vulnerability, and death, we tried to verify through a literature review of scientific articles published in the country in the last years what psychologists were able to discuss. To do so, we established two main categories – transgender and psychology – for our survey, which was crucial to contextualize the issue of transgender mental health in the actual academic approach to the problem. Our first observation after the survey is that there have been relatively few publishing in the decade; we only found 29 articles.17,21,31,43-68 We could verify that psychologists from five orientations – Psychoanalysis, Gestalt-Therapy, Existential-Phenomenological, Cognitive Behavioral, and health care – began to discuss the matter. However, only 31% published some information on individual interviews. They all contained literature revision and historical contextualization; half claimed attention to the need for depathologization, and 31% were concerned with public health policies. The relatively few developments in psychological interviews showed us the importance of making some advances in this orientation. We must say that the publication of articles takes more than two years in the country and that the survey we could develop does not consider more recent studies. This is quite unfortunate because we know that in the past two years, congresses, new articles, and other academic activities did discuss the subject. We will have to examine them in a further study. From our experiences and notes of appointments, we then developed a simple method that helped us to pinpoint four issues often manifested in the narratives of the 13 participants of the research. Four predominant issues dealt with the experience of each participant. We identified them as an issue that testifies to some conflict they had undergone or was still undergoing within his entourage.

When academic production is out of step with what is seen in clinical practice, that is, in mental health care, this points to a still significant limitation of the academic-scientific approach on the experience of each one, in this case, the trans population. The normative expectations stigmatize the trans population; that is, the cultural expectations of a cisnormative system restrict the transgender experience, foster pathologization, and increase discriminatory and segregating practices.38,69 The four predominant themes of the narratives of the semi-structured interviews dealt with both the experience of each one and the conflict inherent to the classifying terms, sometimes leading to stigmatization. We came across very creative scores used by the participants to escape any possible immobility dictated by stigmas. Thus, as for the social name, 76.9% somehow kept the root of their given name, finding a variant from there. The majority, 64.2%, of the participants did not think that genital GAS was necessary or desirable, even if 100% had started/undergone hormone treatment. Scores testified above all to individual differences, the question of how each transgender person became aware of and/or was introduced to the discovery of their gender identities. It is worth noting that, in the discourse of transgender females, although they did not initially know how to name the strangeness with the body as transgender, they already knew about their gender identity, as Participant 1 clearly reveals to us: "I always thought I was a woman. When I was little, I thought all women had what I had. I saw my sister's and imagined theirs would grow." However, in the case of transgender males, we found the use of identification as a way of categorizing as trans what the subject perceives in the gender incongruity, as indicated in the statements of Participant 8, for instance: "I met some people, and they started talking about transgender males, and I identified with that. That is who I am"; or from Participant 10: "We (him and his mother) found out by watching a documentary, and I even started crying." From Participant 11: "An ex-girlfriend helped me in this process, showed me transgender people, and I looked at a photo and said: That is it! I saw the body and said: This is what I want!" But just like in Participant 1, of a transgender female, who always knew she was a woman, Participant 13 was also sure that he was a man since he was little. He referred to the film Tomboy – a story of a child that the viewer identifies as a boy and is surprised when, at the end of the film, his body is laid bare, revealing female anatomy.

More in-depth studies, which will be able to better articulate narratives of transgender people from our clinical practice, will have to wait for the possibility of reproducing these narratives with a statistical method. Our study being introductory, this was not the aim. We want to highlight that when listening to life experiences, culture, narratives, and practices that occur in a given society, when we take them into account in the debate, this may reveal the particularities of each participant. We think this could help counterpoint stigmatization and segregation, helping to improve the critical situation of this population in the country. Based on our clinical experience and the results of this research, we assess that, for the time being, on the one hand, there is much work to be done, aiming at destigmatization and depathologization. On the other hand, with the construction of this article, we also discovered that there will always be something new and different that transgender people tell us in the individuality of their narratives that are not previously categorized, ratifying the importance of listening to them. This perspective reminds us of the poetic phrase of one of the greatest Brazilian composers, because you are the reverse of the reverse of the reverse of the reverse.” To be reverse of the reverse is to affirm the possibility of being in difference, against what segregation, historically, imposes as non-being, an alternative of forging the creation of absolutely singular subjective paths fundamental in the fight for dignity and respect for transgender people.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2024 Marques, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.

World Eating Disorder Week is observed from 23 February 2026 to 01 March 2026 to increase awareness of eating disorders and their psychological impact, and to promote early intervention and recovery. This initiative highlights the role of psychology and clinical psychiatry in understanding and treating eating disorders.

Researchers are encouraged to submit relevant research articles, reviews, and clinical findings. Submissions received during this week will receive a 30–40% publication discount in the Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry (JPCPY).

.