Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6410

Research Article Volume 15 Issue 2

1Department of Neurology, Sydney Children’s Hospital, University of New South Wales, Department of Paediatrics, Women’s and Children’s Health, University of New South Wales, Australia

2Department of Paediatrics, Women’s and Children’s Health, Australia

3Department of Neurology, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Australia

4Department of Dietetics and Nutrition, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Australia

Correspondence: Michael Cardamone, BSc(Hons) PhD MBBS FRACP 1Sydney Children’s Hospital, Department of Neurology, High Street, Randwick, Sydney, NSW Australia 2031 & 2 University of New South Wales, Department of Paediatrics, Women’s and Children’s Health, UNSW Medicine, Sydney NSW 2052 Australia, Tel +61 2 93821847, Fax +61 2 9382 1580

Received: March 20, 2025 | Published: April 2, 2025

Citation: Cardamone M, Banuelos R, Beavis E, et al. Parental perspectives on dietary therapy for children with intractable epilepsy: factors influencing efficacy, tolerability and compliance. J Neurol Stroke. 2025;15(2):22-27. DOI: 10.15406/jnsk.2025.15.00616

Purpose: To explore parental perceptions of the KD service delivery at a single centre and how these affected compliance, efficacy and tolerability of children with intractable epilepsy on the KD. Additionally, to identify strengths and weakness of the KD service and provide strategies to improve service delivery and optimise treatment compliance of children and families commencing the KD.

Method: 42 of 90 families whose children had commenced the KD at our centre between1997-2015 completed the parental perspectives questionnaire. Parental reported side-effects attributable to the KD were explored along with perceived tolerability of and compliance with the KD and parental perceptions of seizure reduction and cognitive improvement. Parental views concerning initiation, maintenance, follow-up, and suggestions for improving delivery of the KD were also explored.

Results: Most parents felt satisfied, confident and supported during their experience with the KD. They reported difficulties with preparation and increased time required to administer the KD (31%), disruption of family dynamics (24%), compliance/understanding of others in the child's care network (19%), and food refusal (19%). Parents whose child stayed on the diet for longer were more likely to cite overall cognitive or developmental gains and the degree of parent-reported reduction in seizure burden was associated with parental perceptions of these gains. Additionally, greater parent-perceived reduction in seizures was associated with diet duration. Parents suggested further dietetic support, frequent KD follow-up clinics, and parent mentorship to improve delivery.

Conclusions: Parents valued the efficacy of the diet, yet acknowledged the increased burden of

Keywords: intractable epilepsy ketogenic diet, patient compliance/adherence parental perspectives treatment outcome

AED, anti-epileptic drug ie intractable epilepsy; KD, ketogenic diet; MAKD, modified Atkin’s ketogenic diet; MCT, Medium-chain triglyceride

The prevalence of childhood epilepsy is 4-5 per 1000 children.1 Seventeen percent of children diagnosed with epilepsy will have intractable epilepsy (IE)2 where seizures will persist despite treatment with at least two tolerated and appropriately dosed anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs).3 IE has been associated with greater morbidity (including neurological impairments)2 and mortality.4 Moreover, greater seizure burden and polytherapy has been associated with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.5

The ketogenic diet (KD) has been used as an alternative treatment to AEDs since the 1920’s and has experienced a resurgence in its use over the past two decades.6 The classical KD typically provides a 4:1 ratio of grams of fat to grams of carbohydrate and protein combined, and has been shown to reduce seizure frequency by >50% in over 50% of treated children.7 Modern versions of the KD include the modified Atkins ketogenic diet (MAKD), medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) diet, and low glycaemic index treatment. These non-classical diet variations allow increased carbohydrate and protein intake thereby promoting greater meal flexibility and palatability without sacrificing seizure control. These are important considerations, particularly for the older child, young person or adult.8–11

Given the restrictive requirements of the KD, compliance can be an issue and discontinuation rates over 50%12 have been reported. Poor compliance and persistence with the KD have been attributed to a range of adverse side effects such as gastrointestinal problems, biochemical disturbances and poor growth,13 poor tolerability of unpalatable meals in children, and challenges faced by parents including time constraints and food preparation.14,15 The analysis of diet discontinuation is often variable and unsatisfactory, resulting in the inability to clearly determine the clinical characteristics of children likely to stop the diet.12

To date there has been little data examining parental attitudes and perspectives relating to the KD and how these might contribute to compliance and discontinuation rates.14–17 Examination of contributing patient and family factors influencing compliance warrants further investigation. The aim of this study is to explore parental perspectives on the strengths and weakness of the KD and how these might relate to compliance and persistence with the KD. A better understanding of difficulties associated with the diet and reasons for discontinuation will allow for service delivery modifications where necessary and interventional strategies prior to KD commencement with a view to improving treatment compliance and persistence.15

Recruitment

This was a cross-sectional study of parental perceptions of the KD. A questionnaire was offered to families of children identified as having commenced the KD at SCH between 1997 (Figure 1) and 2015. An invitation letter, information and consent form, and study questionnaire were sent to the parents or caregivers of all eligible participants or offered at clinical follow-ups in the hospital.

Outcome measures

A survey was designed to capture parental perspectives relating to: KD type; duration on the KD; perceptions of seizure reduction, cognitive or developmental improvement, and side effects; factors affecting tolerance and compliance of the KD in their children; experiences and challenges during initiation, maintenance and follow-up of treatment with the KD; and recommendations regarding service improvement (Appendix A).

Data analysis

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are expressed as numbers of patients (percentages) and median (range). Emergent themes in open-ended questions were analysed and expressed as frequency counts (and percentages).

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 25. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Percentage change in seizure burden scores were computed based on retrospective parent-reported seizure burden at diet commencement and at 6 months post initiation where data was available (so that higher % change scores indicate greater reduction in seizure burden).

One-way ANOVA was used to explore differences in perceived seizure burden across four diet types (KD, MAKD, MCT, and combination). Linear regression explored whether perceived change in seizure burden was associated with diet duration. Binary logistic regression was used to determine whether perceived cognitive or developmental improvement (reported as Yes/No) was associated with perceived change in seizure burden. Independent t-tests were used to determine whether patients or parents who reported cognitive or developmental improvement (yes/no) persisted with the diet for longer.

KD Initiation protocols

For the purposes of this study, the term KD collectively refers to all forms of the KD including the classical KD, MAKD, with or without the addition of MCT oil. The KD initiation protocols at SCH are described in Appendix B.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided from The Sydney Children’s Hospital Network ethics committee. Patient names and medical record numbers were de-identified and stored on separate databases to ensure patient confidentiality.

Demographics

Families of 42 patients returned the questionnaire. The median age of the children at the time of survey completion was 6.13 years (range 1.2-19.7) and they had been using the KD for a median of 17 months (range 1-228 months). Twenty-five children (59.5%) had used the Classical KD, 14 (33.3%) MAKD and 7 (16.7%) the MCT oil diet (n=2 missing) (six of these children had used 2 or more KD types). The KD type for two patients was not reported by parents.

Parental concerns regarding KD side-effects

Parent-reported KD side-effects are presented in Figure 2. The most commonly reported side-effects were constipation (n=20, 47.6%), lethargy (n=19, 45.2%) and diarrhoea (n=16, 38.1%). Long-term effects on health, such as weak bones (n=2, 4.8%) and kidney stones (n=2, 4.8%) were less common.

Parental experiences of the ketogenic diet

Parental responses to close-ended questions examining aspects of the diet including preparation, confidence, diet support, and follow-up are provided in Figure 3. While most parents felt confident and supported during their experience with the KD, 30 (71.4%) respondents reported they were initially anxious or worried about starting the diet at inception.

Parental narratives in response to open-ended questions provided further insight into their experiences. Commonly cited parental concerns included the child’s compliance with and tolerability of the diet (n=14, 33.3%), diet side- effects (n=10, 23.8%), other long term health effects of the diet due to its high fat and low protein content (n = 9, 21.4%), time needed to prepare meals (n=7, 16.7%), and the restrictive nature of the diet (n=6, 14.3%). These worries did not resolve after diet initiation for a small number of parents (n=7, 16.7%).

For those parents who overcame initial pre-diet concerns, seeing their child successfully comply with and eat the diet (n=8, 19%), and the benefit of experience over time, were frequently cited reasons for overcoming initial anxiety (n=8, 19%). The latter was frequently attributed to side-effects not eventuating and greater confidence with practice in meal preparation.

Ten respondents (23.8%) did not feel adequately prepared for diet initiation prior to hospital admission, and 3 (7.1%) did not feel fully confident continuing the diet at home after discharge. Although 30 (71.4%) respondents felt that the pre-diet information and education supplied by hospital staff was adequate, reported shortfalls included inadequate pre-admission information (n=6, 14.3%) and difficulties understanding the information provided (n=2, 4.8%).

Parent-perceived seizure reduction

After excluding those with incomplete data (n=12), parent-perceived change in seizure burden was computed for 30 patients. Mean parent-perceived seizure reduction 6 months after commencing the KD was 61.42% (range: 0%- 100%), median reduction was 65.53%. Parent-perceived change in seizure burden did not significantly differ across diet types: (i.e. KD, MAKD, MCT, or a combination of diets) (p=.841).

A log transformation was performed on the diet duration variable prior to regression analyses, due to skewness in the data. Results revealed a significant relationship between parent-perceived change in seizure burden and diet persistence (p=0.015), whereby for every 1% increase in the change in seizure burden (reflecting improvement), there is 0.012 month increase in diet duration (Figure 4).

Parent-perceived change in seizure burden grouped according to patients experiencing: 100% reduction (seizure freedom), >90% reduction, >50-90% reduction, >25-50% reduction, and 0<25% reduction.

Parent-perceived cognitive/developmental change

Thirty-one of 42 parents (73.8%) retrospectively indicated they had witnessed cognitive improvement in their child after commencing the KD, while twenty-eight (66.7%) reported observing developmental improvement in their child. In 7 (16.7%) children, cognitive improvement was reportedly evident immediately upon commencing the diet, 9 (21.4%) experienced improvement over 0-3 months, and a further 9 (21.4%) over 3-6 months.

Logistic regression analyses (n=29) revealed that parent perceptions of both cognitive and developmental improvement (i.e. yes/no) were significantly associated with the degree of perceived change in seizure burden. The results indicate that for every 1% change in perceived seizure burden, there was a 7% increased chance of cognitive or developmental improvement (cognitive: OR=1.07; 95%CI=1.02-1.13, p=0.013), (developmental: OR=1.07, 95%CI=1.01-1.13, p=0.013).

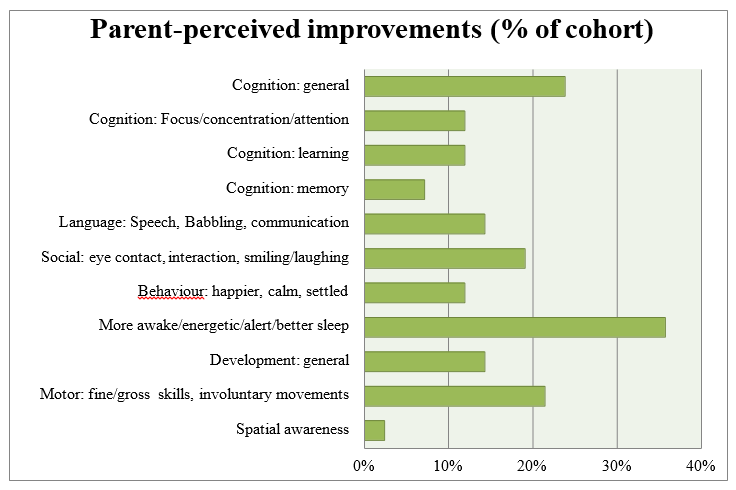

Independent t-test analyses revealed that parents of patients who stayed on the diet for longer were significantly more likely to cite cognitive and developmental improvement in their child (versus no improvement) (p=0.012), (p=0.016) respectively. Qualitative analysis of emergent themes relating to specific areas of parent-reported cognitive and developmental improvements are summarised in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Parent-reported improvements while on Ketogenic Diet, grouped according to emergent themes.

Parental recommendations

Commencing the KD

Parents identified ways in which their pre-diet preparation could have been improved, including: more recipe ideas (n=8, 19%), and contact with other parents with previous KD experience (n=7, 16.7%). Access to more recipes (n=4, 9.5%), cooking practice (n=3, 7.1%), hospital support (n=3, 7.1%) or a parental support group (n=2, 4.8%) were cited as strategies that may have increased confidence managing the diet at home. For those who felt confident maintaining the diet, adequate correspondence with the hospital KD team (n=12, 28.6%), and the ability to find or create tolerable recipes for their child (n=8, 19%) were the most cited factors influencing confidence.

Sixteen (38.1%) out of 43 respondents experienced problems during their hospital admission for commencement of the KD, mostly relating to the inappropriate provision of foods by the kitchen staff (n=5, 11.9%) and food refusal by their child (n=5, 11.9%). Seven (16.7%) parents did not feel fully supported by the KD team and medical staff during their hospital admission. Both the parents who experienced problems during admission and those that did not feel supported shared the view that more direct assistance and time with dietitians to provide a more personalised selection of recipes and practical information specific to their child would have helped.

Parental opinion regarding whether the KD could be satisfactorily commenced in the outpatient setting with daily education visits for one week (versus inpatient admission), was explored. Fourteen (33.3%) respondents supported this approach, however the majority 20 (47.6%) were not in favour. Five (11.9%) felt it could be suitable depending on multiple factors. The reasons parents preferred to commence the diet in hospital included: medical supervision in the event of complications (n=17, 40.5%), availability of constant support (n=12, 28.6%), and the opportunity for education (n=8, 19%). Parents cited adequate provision of education and regular phone contact with the diet team as important requirements for outpatient initiation. The questionnaire did not differentiate between the classical KD or the MAKD, however some parents felt the MAKD would be more suitable for outpatient initiation than the classical KD.

Maintaining the KD

Frequently cited challenges of the diet obtained via open-ended questions included: the time and organisation required of the diet (n=13, 31%), the disruption to family dynamics (n=10, 23.8%), the degree of understanding of other people in the child’s care network and their support of diet compliance (n=8, 19%), and problems of food refusal and diet compliance in the child themselves (n=8, 19%).

Responses obtained from Likert type scales rating parental perceptions of the barriers around the use of the KD were in keeping with qualitative themes. Nineteen (45.2%) and sixteen (38.1%) respondents either agreed or strongly agreed respectively, there was “no local support available to administer the diet” and “the amount of time involved in preparation was too much for my family,”. In addition, 10 (23.8%) respondents agreed or strongly agreed that cost was a barrier to the KD, and 9 (21.4%) felt that poor efficacy contributed as a barrier to its continuation.

Figure 6 illustrates parent responses to what they believed would assist with implementing and maintaining the KD. Provision of cookbooks and home menus were frequently endorsed as potentially beneficial for overcoming the issues of organisation and time constraints. Similarly, outpatient monitoring services in local communities and increased telephone support were recommended.

Follow-up of the KD

71.4% of respondents felt that they received adequate follow-up during the KD. Many acknowledged that they were able to contact the dietitians over the phone or via email whenever they needed. Despite this, the overwhelming majority (n=35, 83.3%) thought a dedicated KD follow-up clinic would be helpful. Other than the dietitian, neurologist and epilepsy nurse, respondents would like to see other parents/families (n=9, 21.4%) or a dedicated person to provide recipes and cooking classes (n=4, 9.5%). Most respondents wanted this clinic to be more frequent when first starting the diet, and then every 1-3 (n=10, 23.8%) or 3-6 months (n=13, 31%) once established on the diet. Only 3 respondents (7.1%) felt that they had enough follow-up clinical appointments already.

This study explored parental perspectives on the ketogenic diet including side effects experienced, factors affecting initiation and maintenance, tolerance, compliance, and perceptions of seizure reduction and cognitive or developmental gains. The most commonly reported side-effects were constipation, lethargy and diarrhoea, consistent with the literature. Most parents felt satisfied, confident and supported during their experience with the KD. Reported difficulties of the diet included: food preparation, time required, disruption to family dynamics, compliance, and food refusal. Reports of children being more alert/ awake/ energetic, and more social, engaging and communicative whilst on the diet, were common themes. Parents whose child stayed on the diet for longer were more likely to cite overall cognitive or developmental gains and the degree of parent-reported reduction in seizure burden was associated with parental perceptions of these gains. Additionally, greater parent-perceived reduction in seizures was associated with diet duration. In terms of suggestions for improvement, parents suggested frequent KD follow-up clinics, further dietetic support, and parent mentorship to help improve delivery.

Side effects on any KD are common. Mild gastrointestinal symptoms were some of the most commonly reported side effects in this study by parents, consistent with the literature,18 with long-term side effects being less frequently reported by parents. The short and long-term side effects of the KD remain a significant parental concern in our sample, but fortunately the majority of parents could overcome these concerns. Although early- onset side effects rarely lead to diet discontinuation,13 similar questionnaire studies show that many parents express the desire for more education in order to anticipate, treat and prevent side effects more appropriately.16 In our study, many parents felt the need for extra dietetic support and more frequent KD follow-up clinics.

Many barriers to the KD contributing to non-compliance have been previously described.14–17 This study found contributing factors included: the restrictive nature of the KD, the overwhelming amount of time required by parents, but also the organisation and preparation it requires with limited support. Only one article to date explores specific parental (rather than clinician) perspectives of how the above barriers can be overcome and how the delivery of the KD can be improved.14 These parents indicated that solutions might include: providing more dietitian resources to call upon, providing a parent mentor network, improved food selection and formal classes.

A novel theme that emerged in this study was parental concern regarding the compliance of other people in the child’s network of care, including extended family, teachers and even nurses. The majority of parents agreed better educational resources for these parties should be available. They also expressed a desire for better understanding of the KD by all treating medical staff to ensure children are delivered low-carbohydrate foods and medication whilst in hospital, and that ancillary staff recognise the potentially serious consequences for the child if ketosis is not maintained. One mother expressed disappointment that her seizure-free son had being given an infusion containing sugars whilst in hospital by nursing staff which she felt "potentially cost our son a normal life." This demonstrates the huge emotional impact on parents of IE, including the grief associated with loss of a normal life, the pride parents have in being able to care for their child, and trust issues surrounding medical professionals.

Effective communication and collaboration between clinicians, careers and parents is essential to ensure optimal patient care and outcomes. The data obtained via parental questionnaire reveals parent-perceived reduction in seizures was significantly related with the duration the child stayed on the diet. Additionally, over 70% of parents felt their child had displayed cognitive or developmental improvements following diet commencement and these perceived gains were more likely to be cited by parents whose child remained on the diet for longer. Such gains have the potential to improve the parent-child relationship. This study adds weight to the idea that experiencing a positive outcome, specifically, a perceived reduction in seizure burden and/or perceived gains in cognition or development at some point during diet therapy, may motivate families to continue the diet. The importance of these reported gains should not be underestimated and further research into this area would be beneficial.

Cognitive improvement has been increasingly recognised as an important outcome in relation to the KD and is an area of research requiring further evaluation.19,20 A study by Farasat et al. that included 100 patients initiating the KD showed that a major goal of as many as 90% of the families surveyed was to improve their child’s cognition. They also noted that achieving or surpassing parental expectations regarding cognitive improvement correlated with longer persistence on the diet17 in keeping with our findings. The authors suggested cognitive and developmental improvement should be assessed formally in any child commencing KD. While neuropsychological studies are currently in progress, difficulties lie in accurately assessing children with severe neurological handicap, a feature frequently seen in children with epileptic encephalopathies. Thus far, studies have used functional assessments such as the VABS and Gesell developmental scales to assess neurodevelopmental improvements however these also have limitations.19

Despite the current international trend towards offering outpatient commencement of the KD with a view to reducing family disruption and stress,21,22 the majority of parents in our study felt that commencing the KD this way was not desirable, especially with the classical KD. This was based on their opinion that the KD requires medical supervision and support, which would be better served in an inpatient setting. Some families also preferred the intense educational and confidence building process associated with inpatient initiation.21 As one parent commented;

“I feel the diet only succeeded for us as a family because I was committed for a whole week without any distractions. I would research recipes, ask questions, make sure my child was doing well. If I was at home, I am sure there would be so many other things going on. Once your hospital stay is finished you feel more confident.”

However, many parents surveyed agreed that outpatient initiation was possible, especially for children commencing the MAKD and for those who live close to hospital, providing parents were given appropriate

education, phone contact, cooking lessons, and support. This follows the international KD guideline recommendations regarding commencing the KD as an outpatient in carefully selected fully-screened populations.22

A persistent emerging theme in our study was that parents would like to meet other families of children using the KD both before diet initiation and at follow-up clinics in order to share recipes and practical advice. Parent mentors might inspire confidence before KD commencement, as well as online support groups. Parents were also of the opinion that more personalised recipe ideas that take into account the child’s food likes and dislikes would be beneficial as well as supermarket walkthroughs identifying keto-friendly foods and sweeteners. Education sessions without the child present should be considered.

This study is not without limitations. As our service initiates approximately 10 patients on the KD per year, we conducted a retrospective study of parental perceptions to increase sample size and power. Using retrospective parental accounts of diet experience including perceived reductions in seizure burden is subjective and limited by retrospective recall bias given the variability in time elapsed between diet cessation and completion of the questionnaire. Similarly, using retrospective parental reports of cognitive and developmental gains as opposed to objective measures administered at different time points is a further limitation of this study and may limit generalisability of the findings. Finally, the diet delivery at our hospital has changed over time since we first offered the service in 1997 (most drastically with the recent introduction of outpatient initiation for the MAKD), hence some parental responses may reflect practices which have changed over time. Despite these limitations, the results provide important insight to parental perceptions of their experience and warrants further prospective research.

Longitudinal, prospective, multi-centred studies with larger cohorts and longer-term follow-up would greatly add to the available literature by providing greater power to analyse data and accurately assess seizure reduction, side effects and growth patterns of children on the KD. Outcomes that warrant further evaluation include sustained AED reduction over time, continued seizure control and cognitive improvement following diet cessation, and the long-term effects on health and growth.18,23,24 Additional avenues for future research include KD success and parameters such as quality of life,14 formal comparison of neurocognitive and developmental assessment before and after experience of the diet,19 and socioeconomic status.15

Few studies to date have explored parental perspectives on compliance and tolerability of the KD and ways to improve service delivery. Our research goes some way to reducing this knowledge deficit. Parents stressed the importance of dietetic support and education, recipes, more frequent follow-up clinics, and potential parent mentor support networks. Parents reported that the secondary benefits of the KD included cognitive and developmental improvement. Where parents perceived a reduction in seizure burden, patients remained on the diet for longer.Moreover, the parents of children who stayed on the diet for longer were more likely to report cognitive or developmental improvement. Clearly there is potential and the need for further research in this area.

We thank the parents and families of children who have used the KD. We would also like to thank A/Prof Boaz Shulruf (University of New South Wales) and Kylie-Ann Mallitt for providing statistical guidance for this research project.

The authors declare no potential, perceived or real conflict of interest.

©2025 Cardamone, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.