Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 15 Issue 4

Diploma in Economics, specialised as health-economist in dentistry, former Head of Department of “Dental Care“ in the Federal Ministry of Health, Bonn/Germany and German representative in the Council of European Chief Dental Officers (CECDO), ret, Germany

Correspondence: Rüdiger Saekel, Marienburger Str. 28, D53340 Meckenheim, Germany

Received: September 25, 2024 | Published: October 21, 2024

Citation: Saekel R. The current state of oral health and dental care system efficiency in twelve selected East European countries. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2024;15(4):165-177. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2024.15.00631

Objective: This investigation aims to highlight the often-overlooked landscape of oral care in East European countries by evaluating the dental status of their populations and the efficiency of their dental care systems.

Method: The study employs the Dental Health Index (DHI), which measures the dental state of entire populations, allowing for quantifiable comparisons between differing countries and dental systems. The survey relies solely on existing epidemiological and various scientific data.

Results: The findings reveal a wide range of results among the countries studied. On average, the oral health of the younger generation is satisfactory and has improved over the past two decades, with more significant progress observed in permanent teeth compared to deciduous teeth. However, the dental status of adults remains poor, with only a few signs of positive developments in the past decade. The most favourable DHIs are seen among Romanian and Serbian individuals, while Lithuanian and Bulgarian citizens exhibit a less favourable oral health status. Notably, the latter two countries have the highest dental density of those studied. In terms of benefit-cost reflections, Romania, Serbia and Poland perform best. Estonia and Lithuania appear to have untapped productivity resources.

Conclusion: To enhance the overall oral health status of the population, the author advocates for a broader focus that extends the current prioritization of the young generation to include adults up to 35 years of age, as the period between 18 and 35 years significantly influences the future development of natural teeth. To implement effective measures for this reform, oral health policies must prioritize prevention and tooth retention. Suggestions are provided on how this could be achieved. An active, goal-oriented oral health policy is essential, for improving the currently unsatisfactory oral health status of adults. Without such efforts, the dental health of the elderly population is likely to deteriorate further.

Keywords: oral health status of East Europeans, performance of East European dental systems, macro-level country comparison of oral care provision, benefit-cost analysis of dental care in East Europe.

While the oral health situation in Western European countries is well-documented, there is significantly less information regarding the oral health status of Eastern European societies. The differences in development between Western and Eastern European countries were primarily influenced by the presence of the "Iron Curtain." Since its fall in 1989, many Eastern European nations have gradually begun to overcome decades of stagnation and are engaged in a process of catching up, especially in socio-economic terms. More than three decades later, it is time to assess this ongoing development phase, particularly concerning dental health from a population perspective and the effectiveness of the dental care systems in transition. It will be interesting to see whether Eastern European countries can start a catching-up process with their Western European counterparts. The prospects for such improvements appear promising, as it is typically easier to adopt best practices from more developed countries than to forge new paths into an uncertain future.

Research on oral health in Eastern European states was initially addressed in the work of Patel,1 which included a study of seven Western European countries alongside three Eastern European nations: Lithuania, Poland, and Romania. Patel and their team concluded that despite dramatic declines in caries prevalence in Western Europe, oral diseases continue to impact many areas of Eastern European societies. However, some of these countries have implemented effective population-based preventive programmes. For example, water fluoridation has been adopted in Poland and Serbia, while fluoridated salt has been introduced in Slovakia and Czechia, and fluoridated milk programs for children have been initiated in Bulgaria. Additionally, Eaton et al. included Hungary, Poland, and Romania in their study of eleven European countries focusing on the provision and cost of oral healthcare.2

A recent comparison of national oral health policies, financing, and dental status across nineteen countries worldwide also included four Eastern European states: Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovenia. The central findings of this groundbreaking study indicated that increases in dental care costs and the presence of mandatory dental services for children are correlated with a significant reduction in caries affection.3 These results clearly highlight the necessity and benefits of preventive care, particularly for children and adolescents. Another study looking at 12-year-old adolescents in 36 European countries, including all Eastern European EU members and Serbia, found a negative correlation between income and caries experience.4 The authors noted the strong influence of macro-level socio-economic factors, such as gross national income, unemployment rates, and per capita expenditure on dental healthcare, on the dental health of adolescents, and advocated for more macro-level investigations considering both the benefits and costs of dental systems.

Furthermore, a recent report by the WHO on the European Region, which encompasses 53 countries across Europe and Central Asia, found that over half of all adults in this region had a significant oral disease in 2019, marking the highest prevalence worldwide.5 In this European Region, two-thirds of the countries (34 out of 53) lack a national oral health policy, and ten countries spend less than $10 per person per year on dental care, with an additional 14 nations spending between $11 and $50. The majority (72.5%) of countries within the WHO European Region have no tax on sugar-sweetened beverages.6 These alarming figures often pertain to countries from Central Asia, including the Caucasus nations, the Russian Federation, Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, several Balkan states, and many Eastern European countries outside the EU. Consequently, the WHO European Region is highly heterogeneous, making it unsuitable for investigations into more advanced Eastern European states. Therefore, this study will concentrate exclusively on selected Eastern European countries that have achieved a certain economic foundation from which to develop their health systems, including oral health policies. We have included both European Union (EU) members and a candidate country, reflecting a more elevated stage of development.

The objective of this macro-level survey is to evaluate the existing efforts in relatively homogeneous East European countries to establish functioning dental care systems amid transition challenges. We aim to assess oral health status and sustainable financial foundations, while also determining whether some countries perform better than others and identifying potential reasons for these disparities.

This study relies on existing empirical and epidemiological data sourced from several organizations, including the World Bank, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Malmö University Database, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Database, specifically focusing on financial resources within the oral health sector. Additionally, we utilised research papers authored by dental scientists within the East European region. In cases where national representative data were outdated or missing for key indicators or age-classes, we supplemented our findings with local surveys identified through systematic internet research in English-language peer-reviewed journals.

Our focus encompasses the oral health status of the entire population, rather than isolating a single age group that is meant to represent the whole populace. Therefore, we utelise all WHO standard reference age-classes, including 5/6-, 12-, 35/44- and 65/74-year-olds. We also include the value for missing teeth (M-T) in seniors, as this key indicator reflects the cumulative oral disease burden (caries, periodontitis and tooth loss) over a person´s lifetime. For measuring the main oral disorders, we employ the established decayed-, missing-, filled teeth index (dmf-t) for primary teeth and the Decayed-, Missing-, Filled Teeth Index (DMF-T) for permanent teeth. Additionally, periodontal disease is assessed using the Community Periodontal Index (CPI) grade 4 (pocket-depth ≥ 6 mm) as only severe periodontitis is a condition of public health.6

To provide a comprehensive overview of dental health across the population, we use the Dental Health Index (DHI), which aggregates the values from all standard reference age-classes and incorporates the M-T indicator for those aged 65-74. To avoid disproportionately emphasizing the relatively high M-T values in seniors, we convert this figure into index points. A detailed explanation of the DHI construction can be found elsewhere.7–9 The formula for the DHI is as follows: DHI = (Caries-free Index 5/6 + DMF-T 12 + DMF-T 35/44 + M-T Index 65/74 + Edentulism Index 65/74) : 5. A lower DHI indicates a more favourable dental status and a more effective dental care system. The relationship between the DHI - which illustrates the benefits of a dental care system - and the cost aspect, defined as the proportion of total outpatient oral health care costs relative to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is articulated through the Efficiency Index (EI). This is calculated as follows: Efficiency Index (EI) = Dental Health Index (DHI) + Dental Care Cost Index (DCCI). The DCCI encompasses all dental care expenditures, including government spending, health insurance, voluntary health insurance, and out-of-pocket payments, enabling comparisons of cost levels across different care systems and financing methods. This approach is advantageous for conducting cross-country comparisons particularly in oral healthcare systems. By combining these indices, we ensure that they indicate improvements consistently. Therefore, a lower EI signifies a more favourable benefit/cost ratio within an oral care system. We chose 2019 as the reference year for cost comparisons, as data from subsequent years are biased due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

These two overall indicators are applied to a group of socio-economically relatively homogeneous East-European countries that are either European Union (EU) members or candidate states. The countries included in this analysis are Bulgaria (BG), Croatia (HR), Czechia (CZ), Estonia (EE), Hungary (HU), Latvia (LV), Lithuania (LT), Poland (PL), Romania (RO), Serbia (RS), Slovakia (SK), and Slovenia (SI). At the end of the 20th century, Lalloo et al. identified a correlation between a country´s socio-economic development-stage and its population´s dental health status,10 a finding recently reaffirmed in various regions of Romania.11 Consequently, we present the indicators GDP per capita and the Human Development Index (HDI) for evaluative purposes (Table 1). All selected East European nations exhibit similar GDP per capita levels and, according to the World Bank classifications, are categorised as high-income countries except of Serbia, which falls into the upper middle-income bracket. Relative to the EU average, these East European countries generally display slightly lower income rates, whith Serbia notably trailing behind. Most have achieved an HDI classified as very high, although Bulgaria remains on the threshold between the very high and high categories. Urbanization rates in the selected countries vary, with four countries (SK, RO, SI, RS) having lower population densities (< 60%; (Table 1).

|

Country |

GDP/capita PPP (current international $) |

Human development index (HDI)1 |

Urbanization grade (%) |

|

BG |

38,689 |

0.7952 |

77 |

|

HR |

45,909 |

0.878 |

59 |

|

CZ |

53,816 |

0.895 |

75 |

|

EE |

48,992 |

0.899 |

70 |

|

HU |

45,942 |

0.851 |

73 |

|

LV |

42,501 |

0.879 |

69 |

|

LT |

51,877 |

0.879 |

69 |

|

PL |

49,464 |

0.881 |

60 |

|

RO |

47,903 |

0.827 |

55 |

|

RS |

27,401 |

0.805 |

57 |

|

SK |

44,650 |

0.855 |

54 |

|

SI |

54,947 |

0.926 |

56 |

|

EU |

60,348 |

- |

76 |

Table 1 Socio-economic characteristics of the selected East European states, 2022/23

References: 12–14.

Our survey is a descriptive and cross-national investigation on the basis of existing data and research results. Unavoidable in cross-country comparisons is the fact that regularly the time-points of the survey data vary in the different countries. Due to the descriptive and observational study-type, evidence of relationships and influencing factors can be reported, but conclusions on cause and effect are limited.

Our investigation adopts a population perspective, necessitating the use of an overall indicator that encompasses all relevant age-brackets. The DHI serves as this indicator and has proven suitable in various studies conducted in high-income, emerging, or lower middle-income African countries.15,16 Table 2 presents the individual indicators for different age groups, illustrating their relationship to the DHI and the ranking of the countries studied. The percentage of caries-free children aged 5 to 6 years varies significantly, ranging from 10% in Lithuania to 52% in Czechia. Four countries (SK, SI, LV, HU) achieve caries-free rates exceeding 40%. In contrast, the remaining countries report very low percentages of caries-free children, ranging from 15% to 29%.

|

Coun-try |

Survey year |

Caries-free 5/6 |

DMFT12 (2) |

DMFT35/44 (3) |

M-T 65/74 |

Edentulism 65/74 |

DHI(6) |

Rank |

|||

|

in % |

Index (1) |

abs. |

Index (4) |

in % |

Index (5) |

||||||

|

BG |

2009/10/2019 |

29 |

7.1 |

3.0 |

16.62 |

15.71 |

8 |

30.71 |

3.1 |

7.6 |

7 |

|

HR |

1999/2013/2015/2019 |

26 |

7.4 |

3.4 |

12.53 |

154 |

8 |

32.01 |

3.2 |

6.9 |

5 |

|

CZ |

2006/08/09-10/2013/2019 |

52 |

4.8 |

2.1 |

17.1 |

11.16 |

6 |

18.7 |

1.9 |

6.4 |

4 |

|

EE |

2013/2018 |

28 |

7.2 |

2.0 |

no data |

13.76 |

7 |

18.1 |

1.8 |

- |

- |

|

HU |

2003/04/08/2013/2016-17 |

43 |

5.7 |

2.3 |

15.4 |

16.6 |

9 |

19.8 |

2.0 |

6.9 |

5 |

|

LV |

1993/2007-10//2019/2021 |

447 |

5.6 |

2.2 |

18.5 |

12.48 |

7 |

24.0 |

2.4 |

7.1 |

6 |

|

LT |

1998/2007/2013 |

10 |

9.0 |

2.0 |

17.4 |

13 |

7 |

23.7 |

2.4 |

7.6 |

7 |

|

PL |

2013/16/2017-2021 |

15 |

8.5 |

2.4 |

14.611 |

13.7 |

7 |

27.91 |

2.8 |

7.1 |

6 |

|

RO |

1995/2008-9/2018/2019 |

17 |

8.3 |

2.1 |

9.09 |

7.610 |

4 |

29.31 |

2.9 |

5.3 |

1 |

|

RS |

2008/2011-12/2013/2019 |

22 |

7.8 |

2.3 |

>10.213 |

≈1012 |

6 |

34.11 |

3.4 |

5.9 |

2 |

|

SK |

2020/2021/ |

45 |

5.5 |

1.4 |

no data |

no data |

- |

29.8 |

3.0 |

- |

- |

|

SI |

1998/2013/17/19 |

447 |

5.6 |

1.5 |

14.7 |

13.16 |

7 |

19.2 |

1.9 |

6.1 |

3 |

Table 2 Dental health index of the population (DHI) in selected East European countries 2010-2020

References: 6, 17–37.

The WHO set a goal for 2020 to achieve at least an 80% caries-free rate among 5/6-year-olds, a target that remains unmet across all East European countries.23 This shortfall is echoed in many West European countries as well, although their average caries-free levels are significantly higher (between 50% and 60%). Only Denmark and Sweden nearly approach this goal, both with caries-free rates of 78%.17 In terms of 12-year-olds, Slovakian (1.4) and Slovenian (1.5) teenagers exhibit the lowest caries burden in permanent teeth. Both countries slightly exceed the WHO's threshold for very low caries burden (DMFT < 1.2). Most other countries fall into the low category (DMFT > 1.2–2.6). Bulgarian and Croatian teenagers exhibit moderate DMFT values, ranging from 3.0 to 3.4, which corresponds to the moderate category (DMFT > 2.7–4.4). Notably, no country falls into the WHO's high category (DMFT > 4.4).

To better understand the development of indicators for these two younger generations over time, Table 3 provides an overview of longitudinal trends in the associated countries.

In the past one or two decades, comparative data for Estonia and Slovakia has not been available. In countries like Lithuania, Romania, and Serbia, where caries prevalence among 5/6-year-olds has risen over time, all other countries show a decline in dmft values for preschool-aged children. Our findings align with recent studies conducted in Hungary23 and Serbia,24 which also reported a positive trend among 12- and 15-year-olds. In both age groups, the proportion of individuals with a caries-free dentition more than doubled. In contrast, an investigation into early childhood caries (ECC) within EU member countries indicates an overall increase in the prevalence of ECC.37

In the other investigated countries, the DMFT trends in 12-year aged adolescents were slightly diminishing. Only in Croatia, the DMFT stagnated over time (Table 3). Striking is that the comparison of dmft values in primary teeth with the DMFT values in permanent teeth (Table 3) reveals that higher rates of caries burden in 5/6-year-olds did hardly influence the level of caries burden in permanent teeth of adolescents. Our study also shows that the GDP per capita has a negligible influence on the level of DMFT in adolescents. Divergent findings of the earlier mentioned Vukovic et al. study4 led to the conclusion that adolescents from Western European countries exhibited 90% lower odds of poor dental health than adolescents from Eastern Europe and that a strong relationship between oral disorders and socio-economic and political contexts exists. An explanation for these different findings might lie in the fact that our study investigates selected and relatively homogeneous East European countries among each other, so that the income differences among the countries studied are not so distinct as in comparisons between West and East European states. Interesting is that the average share of caries-freedom in deciduous (31.3%) and permanent teeth (32.9%) of East European youngsters is almost equal.17 In other words, caries-freedom has not improved during preschool age and 12-year-olds.

|

Country |

dmft 5/6 |

DMFT 12 |

||

|

BG |

1983: 4.3 |

2010: 3.7 |

2000. 4.4 |

2010. 3.0 |

|

HR |

2008/9: 4.7 |

2013/15: 4.1 |

1999: 3.5 |

2015/16: 3.4 |

|

CZ |

1998: 3.7 |

2009/10: 2.9 |

1998. 3.4 |

2008: 2.1 |

|

EE |

- |

2018. 4.0 |

1998: 2.7 |

2018: 2.0 |

|

HU |

1996: 4.5 |

2016/17: 3.6 |

2001: 3.0 |

2016/17: 2.3 |

|

LV |

2000: 3.6 |

2021: 3.0 |

2000: 3.9 |

2021: 2.2 |

|

LT |

1993: 4.4 |

2013: 7.9 |

2000: 3.7 |

2007/8: 2.0 |

|

PL |

1993: 5.4 |

2018:4.7 |

2000: 3.8 |

2019: 2.4 |

|

RO |

1995: 4.4 |

2007: 5.7 |

2000: 2.8 |

2008/9: 2.1 |

|

RS |

1989:4.0 |

1994: 4.8 |

2000: 3.3 |

2019: 2.3 |

|

SK |

1987: 3.4 |

- |

2001: 3.2 |

2021: 1.4 |

|

SI |

1987: 5.2 |

1998: 3.8 |

1998:1.8 |

2017: 1.5 |

Table 3 Current trends in oral health of 6- and 12-year-olds in selected Eastern European countries (nearest available data)

Reference: 17

Before evaluating the middle-aged citizens, we have a look at the oral health development of 15- and 18-year-olds (Table 4).

|

Country |

DMFT 15 |

DMFT 18 |

Percent affected (%) |

|

BG |

- |

6.3 |

91.7 |

|

CZ |

5.0 |

- |

86.4 |

|

EE |

- |

8.91 |

- |

|

HU |

- |

7.6 |

93.9 |

|

LT |

- |

2.9 |

78.3 |

|

PL |

- |

6.5 |

93.2 |

|

RO |

- |

8.9 |

- |

|

RS |

4.1 |

- |

72.0 |

|

SK |

2.4 |

- |

- |

|

SI |

4.3 |

- |

81.0 |

Table 4 DMFT values and share of caries affected adolescents aged 15-and 18-years in selected East European countries, 2020 (or nearest)

Reference: 17

In the span of three years, the DMFT score for 15-year-olds more than doubles in Czechia and Slovenia, and increases moderately in Serbia and Slovakia. Regarding 18-year-olds, the increment in caries is significant: it doubles in Bulgaria, rises more than fourfold in Estonia and Romania, increases by more than threefold in Hungary, and sees a close to threefold increase in Poland (see Table 4). This indicates that the caries increment among teenagers over the age of 12 is notably high in many countries, and the caries affection rates in youngsters aged 15 and 18 are more elevated than in preschoolers and 12-year-olds. This trend highlights a concerning deterioration of caries-free status in older adolescents, suggesting a critical gap in the dental care available for these age groups.

Across all surveyed countries, there is a marked increase in caries prevalence between the ages of 12 and middle age (as shown in Table 2). The most significant increases are observed in Latvia (∆16.3), Lithuania (∆15.4), Czechia (∆15), Bulgaria (∆13.6), and Hungary (∆13.1). In contrast, Romania (∆6.9) and Serbia (∆7.9) show relatively moderate progressions. According to the WHO classification of DMFT levels in middle-aged adults34, Romania, Serbia, and Croatia fall into the moderate range of caries prevalence (9.0-13.9). Meanwhile, most other countries, including Slovenia, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechia, and Lithuania, land in the high category (14.0-17.9), with Latvia even reaching the very high category (>18.0). However, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the limited availability of epidemiological data on middle-aged populations in most countries. It is also important to note that even in high-income countries such as Denmark, Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and Japan, the increase in caries prevalence from adolescence to middle age remains relatively significant (classified as moderate).9

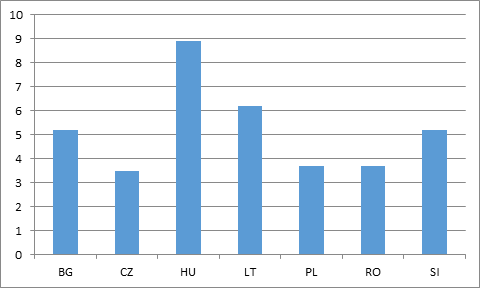

A particularly telling indicator of a dental care system's effectiveness is the percentage of missing teeth in seniors. In Romania, the percentage of missing teeth among seniors is the lowest, followed by Serbia (as detailed in Table 2). The remaining countries have average missing teeth (MT) values ranging from 11.1 (Czechia) to 16.6 (Hungary). While these figures are lower than those in some emerging countries, such as South Africa (MT: 25.2) and Brazil (MT: 20.5),15 they are significantly higher than in high-income countries, where MT values fall between 5.6 and 8.8.9 Among these high-income nations, Germany currently reports the highest value of 11.1,38 matching that of Czechia. In 1997, German citizens aged 65 had an average of 17.6 missing teeth, which is slightly higher than the current levels seen in Eastern European citizens. Germany managed to lower its average from 17.6 to 11.1 missing teeth over approximately two decades, an improvement accomplished through focused and ongoing reforms aimed at enhancing prevention and tooth retention strategies.39 This example suggests that Eastern Europe may be lagging by about 20 years behind high-income countries regarding tooth loss in seniors, a trend that begins to manifest in younger middle-aged individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Missing teeth in adults aged 35/44-year-olds in East European countries 2000-20171

Reference: 17

Among the countries for which data has been collected for this age-bracket, Hungary stands out with an extreme value of 8.9. Lithuania and Bulgaria also report notably high figures for middle-aged adults at 5.2, as shown in Figure 1. When the mean value for Bulgaria is broken down by age classes, specifically 30-39 years with an MT value of 3.4 and 40-49 years with an MT of 6.9,17 it reveals that over a ten-year period, the MT value more than doubled. This serves as an example of how dynamic and serious tooth loss can be for middle-aged adults in some Eastern European countries, posing a significant threat to the natural dentition of the elderly.

Consequently, the rates of edentulism among seniors in all the analysed societies are extremely high. Serbia, Croatia, and Bulgaria stand out with rates exceeding 30%. Slightly lower figures are observed for Slovakia, Romania, Latvia, and Lithuania, which range from 29.8% to 24%. Hungary, Slovenia, Czechia, and Estonia report lower rates, between 19.8% and 18.1%. The average rate of edentulism across all Eastern European countries studied is approximately 26%. In contrast, the average rate of edentulism in citizens of ten advanced high-income countries worldwide is only 9.5%,9 which is roughly one-third of that in the Eastern European societies. This stark difference highlights the significant oral health issues faced by East European countries.

Having analysed the individual indicators across all age-classes, we can now evaluate the DHI for each country, which measures a population's oral health status as well as the effectiveness of its dental care system (Table 2). It is important to note that this assessment pertains only to the homogeneous Eastern European countries, which generally exhibit a comparatively poor dental status relative to more advanced countries worldwide. Thus, the term 'best performer' should be interpreted relatively. The highest-performing countries are Romania (DHI: 5.3) and Serbia (DHI: 5.9), followed by Slovenia (DHI: 6.1). Czechia ranks fourth (DHI: 6.4), while Hungary and Croatia are tied for fifth place with a DHI of 6.9. At the bottom of the rankings, both Lithuania and Bulgaria have a DHI of 7.6. The average DHI for the countries examined is 6.8. In comparison, high-income countries with advanced dental care systems have an average DHI of 4.0, with the best-performing systems in the world being Sweden and South Korea, achieving DHIs of 2.6 and 3.5 respectively.9 These comparisons with dental systems from high-income countries may serve as a reference point for future oral health initiatives in the studied Eastern European countries.

Striking is that Slovenia, having the highest GDP/capita and the most elevated HDI, reaches only the third rank while Romania and Serbia, with an average GDP/capita and a below-average HDI occupy the top positions. As expected, Bulgaria ranks the lowest due to its comparatively low GDP per capita and its HDI, which remains in the high development category rather than the very high category like the other countries observed. In contrast to Bulgaria, the lower rankings of Lithuania and Poland are surprising since these countries are socio-economically better off (Table 1).

When interpreting the findings related to DHIs, we must remember that this composite indicator measures only the retention of natural teeth over a person's lifetime. However, it is equally important to consider whether lost teeth, which are essential for a functional dentition, are replaced or not, as this significantly impacts a patient's chewing ability and overall well-being. Thus, a comprehensive evaluation of a population's dental health status and the quality of its oral health care system is necessary. Although data on prosthetic provision for adults in Eastern European countries is limited, we will attempt to provide some insights based on existing research (Table 5), comparing three Eastern European countries with three advanced high-income countries for benchmarking purposes.

|

Country |

No. of natural teeth |

No. of natural+artificial teeth |

No. of artificial teeth |

|

CZ |

16.9 |

25.6 |

8.7 |

|

EE |

14.3 |

22.5 |

8.2 |

|

SI |

14.9 |

25.3 |

10.4 |

|

CH |

22.2 |

27.0 |

4.8 |

|

DK |

22.4 |

26.7 |

4.3 |

|

SE |

24.5 |

26.7 |

2.2 |

Table 5 Mean number of natural and artificial teeth in the over-50s in selected East European and high-income countries, 2013

Reference: 27

It accordance with our study findings, citizens of three Eastern European zcountries retain significantly fewer teeth as young seniors compared to those in three advanced Western European countries. However, in the Eastern European countries, the average number of replaced teeth is double that found in the Western countries (see Table 5). Consequently, all three Eastern European societies possess functioning dentition (≥ 21 teeth). This ensures a basic level of prosthetic provision for the adult population, although replacement practices vary from country to country. For instance, in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, it is more common to replace up to five missing teeth than in Denmark, Sweden, or Slovenia.27 Among the other Eastern European countries studied, it is known that in Hungary and Romania, the ratio of removable to fixed dentures is approximately 50% to 50%.40,41 A non-representative pilot study conducted at an urban dental social center revealed that around 38% of patients aged over 56 did not wear partial dentures, believing they did not need them.42 Overall, it appears that a sufficient level of basic prosthetic provision exists in the Eastern European countries, although in Romania and several other countries (BG, CZ, EE, HU, LV, PL, RS), rehabilitation dental care is not included in the dental benefit package (see Table 9).

Although our study is cross-sectional, we supplement our investigation with some longitudinal findings. As shown in Table 3, the dental status of the younger generation has generally improved over time in most observed countries. However, the prevalence of caries in deciduous teeth remains high. Notably, only Lithuania, Romania, and Serbia show negative trends in the development of primary teeth, although the data from these countries is somewhat outdated. The data for adolescents aged 12 is much more robust, reflecting a positive trend across all countries, except in Croatia, where the DMFT value has stagnated between 1999 and 2015/16. Positive trends are also reported for adult dental health. For example, in Serbia, the percentage of residents aged 25 and older who retain all their teeth increased from 5.6% in 2006 to 16.5% in 2019. This improvement is attributed to enhanced oral hygiene practices among the population during this time frame. As a result, 55% of the adult population now perceives their general oral health as very good or good, a doubling compared to 2006.43 Similarly, Romania has seen improvement in adult dental health in recent decades,32 echoing trends observed in Hungarian seniors, where edentulism decreased sharply from 53% to 19.8% between 1991 and 2004.30 Encouraging trends are also evident in Lithuania, where the proportion of adults retaining all their natural teeth has increased due to better tooth-brushing habits.44 In Poland, the prevalence of dental caries and missing teeth in adults has decreased, leading to a gradual reduction in edentulism, to the point where the current situation is seen as 'not dissatisfying'35,45 In contrast, the dental status of the adult population in Slovakia is alarming, having made little progress in recent decades.46 This is surprising considering that 5- and 12-year-old Slovakians show the best dental health among the countries surveyed. It appears that Slovakian health policy is primarily focused on children and young adults, neglecting the dental needs of adults and seniors, as evidenced by a high rate of edentulism among individuals aged 65-74. Furthermore, the abundance of epidemiological studies on children and adolescents, contrasted with the scarcity of studies on adults, reinforces this assumption.

To assess the cost-effectiveness of dental care systems in Eastern European countries, we analysed total dental care costs as a percentage of GDP, presented in Table 8. Lithuania serves as the baseline index (100). The most expensive dental care systems are found in Estonia and Lithuania (0.65%). Notably, Lithuanian residents exhibit the poorest oral health status while causing the highest dental care expenditures. The third-highest costs are associated with the Croatian dental care system (0.52%). Countries such as Serbia (0.21%), Romania (0.22%), Poland (0.21%), Bulgaria (0.28%), and Hungary (0.29%) require significantly fewer macroeconomic resources. The remainder of the countries fall between 0.34% and 0.44%. Thus, the cost range varies considerably from 0.21% to 0.65%. Lithuania incurs three times the financial resources compared to Romania, Serbia, and Poland. The percentage of expenditure on dental care in Lithuania and Estonia is comparable to that of high-income countries like Sweden (0.6%) and the USA (0.67%). Many of the ten most advanced dental care systems worldwide allocate between 5% to 6% for total dental care, encompassing both private health insurance and out-of-pocket expenses. Only Canada (0.71%) and Germany (0.77%) are even more costly in this regard.9

In this context, it is interesting to consider a forecast of future dental expenditure in 32 OECD countries, including eight Eastern European states participating in our study. These forecasts, based on per capita spending data from 2015 extending to 2040,47 indicate that in the two countries with the highest current dental expenditure per capita, Germany and the USA, predicted spending will rise by 146% and 113% respectively, maintaining their status as having the most expensive dental care sectors (see Table 6).

|

Country |

2015 |

2040 |

∆ 2015/2040 (in %) |

|

DE |

361 |

889 |

146 |

|

US |

342 |

729 |

113 |

|

CZ |

113 |

284 |

119 |

|

EE |

131 |

258 |

97 |

|

HU |

78 |

178 |

128 |

|

LV |

56 |

128 |

129 |

|

LT |

85 |

129 |

51 |

|

PL |

64 |

144 |

125 |

|

SK |

93 |

164 |

76 |

|

SI |

72 |

193 |

168 |

Table 6 Predictions of future dental expenditure per capita (US$ adjusted for PPP to the 2010 price-level) in selected East European and two advanced high-income countries 2015-2040

Reference: 47, own calculations.

The comparison between the two high-income countries (DE, USA) indicates that the projected growth rates of dental expenditure per capita in most Eastern European countries are similar to those in more advanced countries. But it is to consider that these two types of countries have entirely different starting points. Slovakia and Lithuania stand out, with predicted growth rates significantly lower at 76% and 51%, respectively.

To better understand the developing dental care systems in Eastern Europe, we need to examine the oral hygiene and care habits of the adult population. An overview of these habits is presented in Table 7.

|

Country |

Dentists/10,000 people2 |

Dental hygienists(abs.) |

Yearly dental visits/check-ups (%) |

Tooth-brushing ≥twice/day (%) |

Interdental cleaning/day (%) |

Sugar consume/capita (g/day) |

Smokers(%) |

CPI 4 in 65-74-year-olds (%) |

Tax on sugar-sweetened beverages |

|

BG |

16 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

74.4 |

39.4 |

19 |

no |

|

HR |

14 |

- |

62 |

695 |

53 |

102.8 |

36.7 |

35 |

yes |

|

CZ |

7.6 |

1120 |

- |

- |

- |

88.0 |

30.9 |

- |

no |

|

EE |

10 |

23 |

4910 |

- |

- |

51.4 |

30.5 |

- |

no |

|

HU |

7.1 |

125012 |

47 |

65 |

18 |

55.1 |

32.2 |

11 |

yes |

|

LV |

7.2 |

366 |

- |

- |

- |

86.1 |

37.2 |

- |

yes |

|

LT |

14 |

89012 |

6311 |

45 |

- |

93.9 |

32.3 |

75 |

no |

|

PL |

9.1 |

3606 |

389 |

456 |

109 |

120.2 |

24.7 |

178 |

yes |

|

RO |

10 |

- |

474 |

96 |

- |

74.3 |

28.4 |

4.79 |

no |

|

RS |

2.3 |

174813 |

46 |

58 |

<417 |

67.6 |

40.1 |

- |

no |

|

SK |

5.3 |

- |

52 |

753 |

50 |

60.1 |

31.5 |

4 |

no |

|

SI |

7.4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

77.6 |

22.3 |

- |

no |

Table 7 Dental care habits of adults aged 35-74 in the observed Eastern European countries around 2020 (or the nearest available data)

References: 32, 40–46, 48–57.

To understand the reasons behind better rankings in DHI for leading countries such as Romania and Serbia, we can observe that oral hygiene and behavioural habits largely align with dental knowledge regarding the relationship between dental status and oral self-care. In Romania, for instance, subjects demonstrate acceptable rates of regular dental visits, fairly good tooth brushing habits, low sugar intake, low smoking rates, and minimal periodontal destruction, which indirectly suggests sufficient oral self-care, as shown in Table 7. Serbia exhibits similar oral self-care habits; however, it has a higher smoking rate. The relatively high rate of interdental cleaning may mitigate the negative impact of smoking on oral health. Despite both countries having low urbanization rates (approximately 55%), they achieve relatively favourable oral health outcomes, albeit with significantly different dental densities. Romania has an average dental density, while Serbia's dental density is extremely low, requiring one dentist to serve 4,348 citizens. This scenario makes it all the more remarkable that Serbian residents possess a relatively better dental status. Additionally, Serbia has a longstanding tradition of public oral health promotion, such as the National Week of Oral Health, and dentists actively participate in oral education for children, both in the community and the workplace. Paediatricians and paediatric dentists are also well involved in promoting oral health among preschool and school-aged children.58 This involvement may help explain why Serbia ranks favourably in the DHI.

Conversely, examining the lower-end ranking countries, Lithuania and Bulgaria, we find that their oral care habits align with the results of their dental status. Lithuanian citizens tend to have relatively high dental visit rates, but these visits are rarely for routine check-ups. They exhibit average tooth brushing practices, a high sugar intake, average smoking rates, and alarmingly high rates of periodontal destruction. In Bulgaria, although sugar consumption is low, smoking rates are elevated, and there is significant periodontal destruction among seniors. These factors contribute to the poor oral health status observed in these countries. Interestingly, both nations have a surplus of dentists, with one dentist available for every 625 (BG) and 714 (LT) people, respectively, as noted in Table 7. Further exploration of this issue will occur when we assess the efficiency of different dental care systems.

The relationship between a population's dental status and the financial resources required to provide dental services is detailed in Table 8. Unfortunately, international comparisons rarely offer a simultaneous evaluation of both the benefits and costs associated with dental care systems, thereby preventing us from making definitive statements regarding the system efficiency of various countries or care systems.

|

Country |

Dental health index (DHI) |

Dental care cost index (DCCI) |

Efficiency index (EI)1 (3) |

Rank |

||

|

Value |

Index (1) |

Total costs in % of GDP |

Index (2) |

|||

|

BG |

7.6 |

100 |

0.28 |

43 |

143 |

6 |

|

HR |

6.9 |

91 |

0.52 |

80 |

171 |

8 |

|

CZ |

6.4 |

84 |

0.37 |

57 |

141 |

5 |

|

EE |

- |

- |

0.65 |

100 |

- |

- |

|

HU |

6.9 |

91 |

0.29 |

45 |

136 |

4 |

|

LV |

7.1 |

93 |

0.44 |

68 |

161 |

7 |

|

LT |

7.6 |

100 |

0.65 |

100 |

200 |

9 |

|

PL |

7.1 |

93 |

0.21 |

32 |

125 |

3 |

|

RO |

5.3 |

70 |

0.22 |

34 |

104 |

1 |

|

RS |

5.9 |

78 |

0.21 |

32 |

110 |

2 |

|

SK |

- |

- |

0.34 |

52 |

- |

- |

|

SI |

6.1 |

80 |

0.41 |

63 |

143 |

6 |

Table 8 Efficiency Index of the dental care systems 2019 (LT=100)

Reference: 59, own calculations.

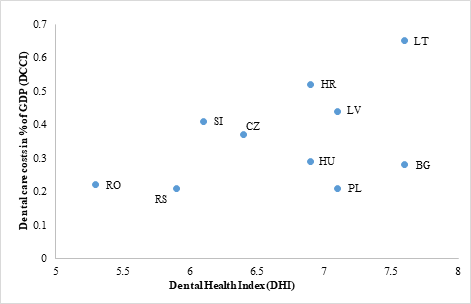

The most efficient dental care system is found in Romania, which has an EI of 104. This indicates that Romania's benefit-to-cost relation is nearly double as good as that of the least efficient system in Lithuania. Serbia ranks as the second most efficient country, and many of the other systems also demonstrate more favourable benefit-to-cost relations than Lithuania. However, for Slovakia and Estonia, no EIs could be calculated due to a lack of epidemiological data. Notably, despite being the wealthiest East European countries, Slovenia and Czechia rank lower in system efficiency compared to the top performers, Romania and Serbia, whose societies are not as affluent. The relationship between the DHI and macroeconomic resources is illustrated graphically in Figure 2. At first glance, the impressive standings of Romania and Serbia are striking. In contrast, Lithuania is easily identifiable as a negative outlier, ranking lowest in both dental health and cost-effectiveness, resulting in the poorest system efficiency. In summary, Romanian, Serbian, and Slovenian societies exhibit dental health that is 70% to 80% better than that of Lithuanian citizens, all while incurring costs that are 30% to 40% lower than those in Lithuania. Overall, the selected relatively homogeneous East European countries display significant variation in dental health status, costs, and system efficiency.

Figure 2 Efficiency matrix of the dental sector in selected East European countries, 2019.1

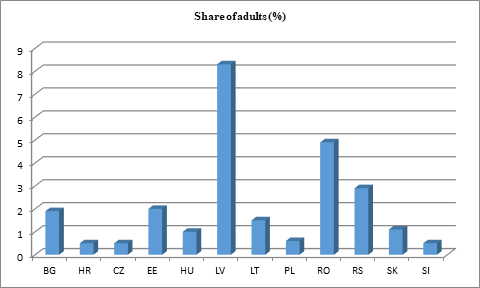

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the dental care system, we include a subjective indicator - unmet needs for dental care due to financial constraints - in our analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Unmet needs for dental examination or treatment due to financial difficulties in individuals aged 16 years and over in selected East Europe countries, 2022.

Reference: 60.

With the exception of Latvia and Romania, most Eastern European societies exhibit very low proportions of unmet dental care needs due to cost, typically under 3%. Given the limited financial resources in all the Eastern European countries studied, this finding is surprising. Other surveys concerning unmet dental needs report higher percentages, even in advanced Western dental care systems.61

To understand the significant differences in the efficacy of dental care and in system efficiency in Eastern Europe, we will explore the reasons behind these discrepancies. It is important to note that all Eastern European states are undergoing a dramatic transition from a state-delivered service model to a system that combines both state and private provision.62 The approaches across the region vary widely, involving public and/or private schemes, clinical care delivery, and the emphasis placed on prevention and oral health promotion. Public services, which are primarily provided by salaried dentists, focus largely on the younger generation, specifically those under 18 years of age. For adults, there is a growing availability of private services, which are often funded out-of-pocket or through health insurance. The prevailing approach tends to be restorative, while prevention and health promotion efforts are largely neglected.63 Some Eastern European countries have started to establish clinical preventive care services.

Table 9 presents an overview of significant characteristics of the current legal systems, including details on benefit packages.

It is remarkable that half of the countries do not have a systematic oral health policy in place. This primarily affects the care provided to adults and senior citizens, which is likely one of the reasons for the widespread lack of epidemiological data on these demographics. However, most countries do have programmes for children and adolescents, although these are often implemented at a local rather than a national level.26,58,65 Given the financial constraints faced by all Eastern European countries, it is highly justified to initially target dental provision toward the younger generation, specifically those up to 16 years old (in BG, LT, and RO) or up to 18 years old (in HR, CZ, HU, LV, SK, PL, and SI).64,66 In Serbia, this provision extends even to students up to 26 years old.58 It is worth noting that the Public Health Insurance System in Romania ceased free dental care in 2013 and currently provides limited funding for young people up to 16 years of age.26 The various programmes for younger individuals have proven to be successful, as evidenced by the decrease in DMFT values for 12-year-olds and the reduction of dmft figures in preschoolers across the majority of observed countries. The only exceptions are Lithuania, Romania, and Serbia with regard to preschoolers (Table 3). Notably, Croatia has a promising initiative that requires parents to present a dentist's certificate confirming that their child has received necessary dental care when enrolling them in school.26

In contrast to general medical care, dental provision for adults is only partially covered by public funding or mandatory health insurance, often requiring out-of-pocket payments. This means that access to dental services also depends on an individual's financial resources,55 unless they fall into the needy category. According to Table 9, adults in Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, and Slovenia primarily pay for dental services out-of-pocket, while Croatia, Czechia, Latvia, and Slovakia offer comprehensive benefit packages. Benefit packages in Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, and Serbia are more limited. Several countries have introduced innovative incentives in their benefit packages to promote regular dental check-ups for adults, such as providing one free examination per year (e.g., BG, HU, PL). Slovakia has similar provisions where basic dental care treatments are funded on the condition that individuals have undergone a periodic examination within the past year.67 In Estonia, insured adults receive a certain amount of money each year (€60 in 2024) as an encouragement to visit a dentist.68

To understand why dental care in some countries is less costly than in others, given their oral health status, a significant factor may be the disproportionately high dentist-to-inhabitant ratio in several Eastern European countries. For instance, Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Romania have higher dentist densities than most advanced Western nations. According to the Global Oral Health Status Report 2023, high-income countries have an average dentist-to-population ratio of 7 per 10,000 people.6 Since most expenses in dental care arise from dentist salaries and incomes, above-average dentist densities can exponentially increase the overall costs of the dental care system. This situation is exacerbated when the licensing of dentists is managed by the Dental Chamber, as it was in Lithuania until 2019. In May 2020, the licensing of dentists and dental professionals was transferred back to the Ministry of Health.70 The aim of this legal change was to alleviate the financial burden of dental care on the population. The surplus of dentists in Lithuania is so pronounced that one-third of dentists practicing in Vilnius claim a shortage of patients,71 despite the average dental consultation rate exceeding one per month,67 which is quite high. Consequently, Lithuania is among the top five countries in the EU where the costs of dental care place the greatest burden on patients.70 With the introduction of the new Law on Dental Practice, the Lithuanian government acknowledged that the profession has 'partially eroded trust with the state, if not altogether with society.' By implementing this law, Lithuania transitioned from having one of the least regulated dental care systems to the most state-supervised in the EU.70 The exorbitant dental care costs, which amount to 0.65% of GDP, too, are driven by a high intake of sugar and a significantly elevated prevalence of periodontal disease among Lithuanian seniors, both of which increase dental demand. Additionally, the extreme costs in the dental sector are further exacerbated by a lack of an effective oral health policy. While the WHO acknowledges that Lithuania has a national oral health policy (Table 9), Vitosyte et al. have pointed out that there is still no department for dental care within the Ministry of Health.71 Consequently, the provision of dental care in the past has largely been left to the private sector, which has resulted in a disregard for prevention and oral health promotion.71

|

Available procedures for detecting, managing and treating oral diseases in public primary care facilities: |

BG |

HR |

CZ |

EE |

HU |

LV |

LT |

PL |

RO |

RS |

SK |

SI |

|

- Oral health screening for early detection of diseases |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

no |

- |

- |

yes |

|

- Urgent treatment for emergency care and pain relief |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

- |

yes |

|

- Basic restorative procedures treating dental decay |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

no |

- |

- |

yes |

|

Oral health interventions as part of health benefit packages: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Coverage of the largest government health financing scheme (% of population) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

- |

- |

100 |

- |

95 |

90 |

85 |

100 |

- |

|

- Routine and preventive dental care |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- |

- |

yes |

- |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- |

|

- Essential curative dental care |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- |

- |

yes |

- |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- |

|

- Advanced curative dental care |

yes |

yes |

yes |

- |

- |

yes |

- |

yes |

no |

no |

yes |

- |

|

- Rehabilitation dental care |

no |

yes |

yes |

- |

- |

yes |

- |

no |

no |

no |

yes |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Existing oral health policy/strategy/action plan |

yes |

yes |

no |

no |

no |

no |

yes |

no |

yes |

no |

- |

yes |

Table 9 Dental system characteristics in selected East European countries 2022

Reference: 48, 64.

Estonia, another country facing high dental costs, also struggles with a burdensome dental care system, as recently reported by a study from the National Audit Office.69 One contributing factor may be the scarcity of employed dental hygienists in Estonia, which could have otherwise helped to reduce system costs. Furthermore, nearly all dental services for adults are provided through private practices, where fees are not regulated.66 In contrast to high-cost countries like Lithuania and Estonia, Czechia, Hungary, and Poland maintain moderate dental costs, in part due to a notable share of their dental workforce being composed of dental hygienists (1,120, 1,250, and 3,606, respectively). Aside from Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, and Luxembourg, nearly all countries in the EU have established dental hygienist schools,72 as these professionals are intended to promote preventive treatment and lower dental expenditures.

On the other hand, Romania illustrates that a higher dental density does not necessarily correlate with extreme dental sector costs, indicating that the type of dental care system plays a critical role. For example, Romania operates under a social health insurance model where district health insurance funds procure services from healthcare providers, thereby exerting some influence over provision costs. Notably, Serbia demonstrates favourable outcomes despite having a very low dentist-to-inhabitant ratio of 1 to 4,348. The explanation may be that dental therapists augment the dental workforce by approximately 80%73 and that extensive public oral health promotion is central to Serbia's future plans to prioritize oral health.64,74

Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that the oral health of preschoolers is unsatisfactory and requires improvement. In contrast, the dental status of adolescents is relatively good in some countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, and is somewhat satisfactory in most others. However, Bulgaria and Croatia still have considerable progress to make. Overall, the long-term development of dental health among the younger generation appears to be positive, with health policies across all countries focusing on these age groups. If existing preventive programs, currently implemented only at a local level in certain nations, were expanded nationwide, we could expect a faster improvement in oral health among young people, potentially reaching the standards of high-income countries for 12-year-olds within a decade.

Epidemiological data for middle-aged adults remains particularly limited, but it shows that most countries exhibit high DMFT values. Only Croatia, Romania, and Serbia report lower DMFT values, ranging from 9 to 12.5, which are typically seen in advanced Western nations like Canada, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Germany.17 The most concerning DMFT value in this age group is found in Latvia, where it stands at 18.5.

The dental status of seniors is overall very poor, as indicated by high rates of tooth loss and edentulism. This suggests a very low effectiveness of the dental care system across all countries. This outcome is not surprising, as most systems have historically prioritized the younger population. Although some countries, such as Serbia, Romania, Lithuania, and Poland, have recently reported higher retention rates of natural teeth, the overall assertion still holds true. Additionally, there are currently no English-language longitudinal studies available for free that provide evidence of significant improvements in oral health among adults.

To enhance the dental status of Eastern European societies while maintaining sustainable dental care costs, dental care systems must prioritize prevention and tooth retention instead of merely repairing damages and passively observing the development of dental diseases. A model for such a system has been proposed for the emerging country of China, which is also transitioning its dental care system.75 Meanwhile, a comprehensive preventive strategy has been integrated into Chinese oral health policy.76 It is important that the focus on prevention and tooth retention guides dental health throughout life, especially for children, adolescents, and young adults, as these generations significantly influence the future state of their natural teeth. To implement these principles effectively, three fundamental cornerstones must be established:

Oral hygiene habits, behaviours, and dietary preferences are developed during childhood and adolescence, and changing improper behaviours in adulthood is often challenging.77 However, dental issues like caries and periodontal disease are chronic, progressive, and cumulative in nature.6 They can lead to significant tooth loss, particularly during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.29,78 Therefore, effective oral health practices, such as regular dental check-ups, should be encouraged from an early age. Also in Eastern European countries, tooth loss is increasing steadily with age. Therefore, health policies should consider gradually expanding dental care services into middle age. This is especially important in nations where there is no established oral health policy or where the benefit package focuses solely on primary oral care (such as in EE, HU, LT, and SI). For instance, regulations could be instituted that allow individuals aged 18 to 35 to access free basic preventive and tooth-retaining treatments, such as annual check-ups, fluoride varnish for high-risk patients, fillings, endodontic procedures, scaling, and polishing, under the precondition that the person regularly has had a yearly check-up at a dentist. During the dental check-up, a caries risk assessment could be performed for new patients. To facilitate this process, a bonus pass system could be introduced to record the check-ups. Additionally, to motivate patients, individuals who demonstrate continuous engagement over five years, verified by the bonus pass, could be eligible for subsidies for dentures if needed. The financing of this system -whether it should be free of charge or involve a co-payment - remains a subject of debate. A similar approach has been successfully implemented in Germany, contributing to improved oral health and significantly reducing the macroeconomic resources spent on dental care over two decades. The percentage of total dental costs relative to GDP dropped from 1.15% (1980) to 0.83% (2005)39 by focusing mainly on preventive and tooth-retaining strategies. As of 2019, this ratio stands at 0.77%.9

A proven method used in several Western countries to manage dental care system costs while simultaneously enforcing preventive procedures is the integration of mid-level professionals, such as dental hygienists and dental therapists,79–81 into the dental workforce. Both the WHO and the World Dental Federation (FDI) strongly advocate for innovative workforce models, because progress in this area has been too slow.82,83 These new workforce models are particularly needed in underserved, mostly rural areas, which are found in less urbanized parts of Eastern Europe. Some Eastern European countries, including Czechia, Hungary, and Poland, have already successfully implemented the integration of mid-level professionals. In regions where dental facilities are sparse, combining teledentistry with mid-level personnel could provide a viable solution. Recent studies have described how this model could function in countries at different stages of development.15,84

To improve the efficiency of the two countries with the highest dental care costs (EE and LT) and the country with the second-lowest efficient care system (HR), addressing the surplus of dentists in these nations is imperative. It seems necessary to guide and plan dentist density; otherwise, costs could skyrocket. In dental care, there is a particularly high risk of supply-induced demand, which can easily lead to overtreatment.71 Such strategies should be accompanied by incentives to create a more prevention-oriented and productive dental team mix that includes mid-level professionals.

This study has certain limitations due to the unexpectedly high scarcity of oral health studies with sufficient epidemiological data from Eastern European countries. Often, only local studies were available, and they varied significantly in methodology. Furthermore, the wide range of years in which these studies were conducted hindered reliable comparisons and evaluations of the countries and their dental care systems. Nevertheless, the author is convinced that it is still possible to extract valuable findings that provide additional insights into the rapidly changing, developing, and still largely unexplored field of dental care in Eastern Europe.

Despite the limited evaluable data from Eastern European countries, this study was able to shed light on the dental health status of economically progressing societies in the region and their dental care systems. It was found that the oral health status of the younger generation has improved over the last decade, achieving a low burden of dental caries. However, adults and seniors still exhibit poor dental health. The author suggests that the oral health of adults in the observed countries could improve if the targeted demographic expands beyond just the younger generation to include young adults up to the age of 35. Additionally, a focus on prevention and tooth retention should be prioritized among both providers and more segments of the population being capable to be influenced. Legal institutions must create the necessary conditions for these changes, as they do not occur spontaneously and require strong political will. To enhance the efficiency of particularly expensive systems (LT and EE), it is essential not only to improve dental health but also to carefully assess whether there are productivity reserves on the providers' side. If such reserves exist, there are strategies available to lower costs in the long term.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflicts of interest.

©2024 Saekel. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.