Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 16 Issue 4

Diploma in Economics, specialised as health-economist in dentistry, former Head of Department of “Dental Care“ in the Federal Ministry of Health, Bonn/Germany and German representative in the Council of European Chief Dental Officers (CECDO), ret, Germany

Correspondence: Rüdiger Saekel, Marienburger Str. 28, D53340 Meckenheim, Germany

Received: August 29, 2025 | Published: October 1, 2025

Citation: Saekel R. Oral health: insights from 50 years of german and swedish practices. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2025;16(3):123-133. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2025.16.00655

Objective: Germany has undergone a paradigm shift in dental care during the development of a modern dental care system. This study evaluates the effects of this shift on methods, oral health, treatment structures, patient behaviour, and costs over a span of fifty years. For comparison, we use Sweden as a benchmark country.

Methods: Our investigation is a macro-analysis conducted from a population perspective, utilising existing representative data sources. The analytical tools include established measurements from the World Health Organization (WHO) and macroeconomic data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Results: Following the redesign of the legal framework of the dental care system toward prevention and tooth retention from 1978 to 2000 and beyond, notable positive effects began to emerge quickly among the younger generation in the early 1990s, with significant improvements observed in young adults since 2003. Remarkable progress in senior dental health was first noted in 2014, leading to notible reductions in the burden of dental caries over the following decade. Compared to Sweden, Germany has made considerable strides in addressing the previous backlog in oral health among its citizens, especially among the youth. However, the overall dental health status of the Swedish adult population remains superior. The long-term changes in Germany's treatment structure roughly align with the observed progress in oral health, indicating a strong shift from prosthodontic procedures to preventive and tooth preserving services, a trend that continues today. Corresponding to improvements in oral health, the necessary macroeconomic resources for the dental sector significantly decreased by nearly 60% between 1980 and 2023, reflecting a similar but less pronounced cost trend in Sweden.

Conclusion: The key finding is that both Germany and Sweden demonstrate that prevention and tooth retention in dentistry lead to superior oral health outcomes and more affordable macroeconomic cost structures. This approach is highly efficient in every respect. Despite the significant advancements in oral health across all ages in Germany, certain areas of dentistry still require increased attention. Specifically, there is a need to improve the proportion of cavity-free primary teeth and to address the persistently high incidence of tooth loss among adults over 40 years of age, which is likely associated with very high prevalence of periodontitis in individuals aged 40 to 65 and beyond. The field of periodontics necessitates an evaluation of current treatment practices in German dental offices. It is suggested that incentives be provided to further strengthen the preventive-oriented approach.

Keywords: dental care approaches, is preventive care advantageous, long-term dental care development in Germany and Sweden, correspond oral health and treatment structures over time, cost-intensity of a preventive dental system, Germany´s dental care stand

Systematic national reviews in dentistry are quite rare, yet they provide significant insights into the performance of various dental care systems and their outcomes. Long-term comparisons between different countries are particularly challenging due to varying timeframes of the investigations. However, it is fortunate that for both, Germany and Sweden, which have advanced dental care systems, representative results are available up until 2020/2023. This allows us to analyse and evaluate a period of systematic dental care from 1973/78 to 2023. In the recent past, Sweden has ranked as the country with the best oral health status among its population in several international comparisons,1 making it an ideal benchmark for Germany.

In Sweden, health policy initiatives began in 1974 with the implementation of the New Dental Act, which established that Swedish counties would be responsible for providing comprehensive dental care free of charge to children and adolescents up to the age of 20. Additionally, the National Dental Health Insurance Act was introduced to cover the adult population.2 Over the years, the age limit for free dental care for young individuals has been adjusted, increasing to 23 years and then decreasing back to 19 years starting in early 2025.3 This legal framework was complemented by the launch of an epidemiological survey in the city of Jönköping, whose population structure was intended to reflect that of the entire country. Repeated cross-sectional studies have been conducted every ten years.2 The sixth survey took place in 2023 and is currently undergoing evaluation, which is expected to continue until 2026.4 Since 2008, another reliable data source for the oral health status of Swedish citizens has been established, and since 2014, it has reported nationwide data,5,6 enabling the reporting of the latest epidemiological findings on the dental status of Swedish individuals, even before the latest data from Jönköping becomes available.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, here referred to as Germany, the first epidemiological studies were initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1973, focused on 13- to 14-year-olds in the Hannover region.7 By the end of the 1970s, various regional studies on 3- to 12-year-olds across Germany were published and regularly updated. An overview is given by Bauer et al.8 However, none of these studies could claim to be representative of the entire country. In 1978, a nationwide survey was conducted among randomly selected patients aged 15 and older from dental practices across eight German regions.9 The results of these surveys revealed a 'catastrophic' dental status among both adolescents and adults.10 Naujocks and Hüllebrand concluded that Germany, having the highest rate of caries spread, is lagging behind industrialised Western countries by approximately twenty years.11 These alarming oral health outcomes coincided with financial costs of oral health care getting out of hand. In 1980, 1.15% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was spent on oral care, a figure that was much higher than that of all other advanced Western countries.12 To illustrate the situation, one statistic stands out: in 1978, Germany topped the world in the consumption of dental gold, using 28.0 tons, while much more populous countries like the USA and Japan used only 21.2 t and 13.0 t of that amount, respectively.13

The combination of a troubling oral health status among the population and rising dental care costs prompted health policymakers and legislators to take action. By the late 1970s, the excessive dental costs were largely attributed to misguided dental care structures. Germany's statutory health insurance, which covers nearly 90% of the population since these times, had an extensive treatment catalogue that included nearly all types of prosthetic procedures. Every treatment was funded by statutory sickness funds, and patients faced no co-payments. This arrangement led both dentists and patients to frequently opt for the most expensive treatment options, which predominantly involved prosthetic dentistry. As a result, prosthetic treatments began to overshadow conservative procedures. In 1970, the ratio of conservative to prosthetic treatments was 65% to 35%, but by 1982, this ratio had flipped to 46% versus 54%.14 The shortcomings of the dental care system during that period were thoroughly documented in the 1987 annual report of the Advisory Council for the Concerted Action in Health Care.15

By the end of the 1970s, it was clear that health policy needed to intervene. A paradigm shift in dentistry and dental provision was necessary, as the collaborative self-governance of dentists and statutory sickness funds was insufficient to address the escalating issue. Moving forward, the focus should shift towards preventive care and conservative treatment. This approach should be prioritised before considering prosthetic procedures. Gradually, the required legislative reforms were implemented, beginning in 1978 with a cost containment measure that introduced a 20% co-payment for prosthodontic treatments. Between 1982 and 2000, additional legal reforms took place, as documented in other sources.14 These reforms were later supplemented by further changes in legal frameworks and self-government. This created a legal framework for dental care in Germany that lagged approximately 20 years behind that of Sweden. Moreover, it wasn't until 2021 that supportive periodontitis therapy was added to the treatment catalogue of the German statutory health insurance.16 This inclusion finally completed a comprehensive preventive and tooth-retaining treatment catalogue also for adults. In 1989, at the initiative of the German Dental Association, the Institute of the German Dentists (IDZ) began conducting regular national representative surveys every eight to nine years (1989, 1997, 2005, and 2014). The results of the latest survey from 2023 have recently been published,17 providing compresensive and current representative data on the oral health development of the German population.

In our study, we analyse the effects that the new framework conditions have had on oral health and how changes in oral health status have influenced treatment structures in dental practices over the last 50 years. To provide a scientifically grounded comparison, we use the corresponding oral health care development in Sweden as a benchmark. This enables us to draw evidence-based conclusions for the future. Moreover, less advanced countries seeking effective and affordable dental care structures might get valuable suggestions for their dental care systems.

Our study is a cross-sectional macro-analysis from a population perspective, focusing on the main oral health diseases: caries and periodontal disorders, which account for 90% of the total costs of dental care. We concentrate our evaluation primarily on the WHO standard age groups: 6, 12, 35-44, and 65-74 years, to encompass the entire spectrum of a population's dental health. Since the last two age brackets, 35-44 and 65-74, are not available for Sweden, we opted to use 40 and 70 years for these two age categories. The entirety of this study is based on existing epidemiological and empirical data.

In Sweden, between 1973 and 2013, approximately 1,000 individuals from the same parishes in the city of Jönköping were randomly selected and clinically as well as radiographically examined. Because the corresponding data for the year 2023 are not yet available, we must rely on the Swedish Quality Registry for Caries and Periodontal Diseases (SkaPa Concept), which covers 7.4 million individuals as of 2019.18 This represents 74% of the entire Swedish population aged 0 to over 65. The SkaPa Concept is a nationwide big data registry that reports de-identified data based on automatic retrieval from electronic patient dental records.5 The latest available SkaPa data relevant to our purpose provides average figures for 6-year-olds (n=104,839), 12-year-olds (n=105,827), 40-year-olds (n=43,162), and 70-year-olds (n=44,354) in the year 2020.6

The data from SkaPa are nearly complete survey data from both public and private dental clinics. They cover 90% of children aged 0 to 19 and 50%-75% of the adult population, as not all clinics are yet included and citizens who do not attend a dentist or dental hygienist are not part of the data. The validity of the SkaPa data has been independently verified for both children and adults. The results were deemed to have 'satisfactory reliability and accuracy' for 6- and 12-year-olds and 'accurate' for adults.19,20

The presentation of caries results is based on the Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) index, which has proven effective in numerous epidemiological investigations. In the Swedish surveys, the definition of carious lesions includes initial lesions, whereas German surveys until 2014 reported only cavitated dentine caries (manifest caries). The most recent German survey from 2023, separately, includes also active initial lesions.21

Here, Germany's long-term statistics only reflect the manifest caries values to ensure statistical continuity. On the other hand, the additional identification of active initial lesions enhances the comparability of caries results between the two countries, noting that the German survey of 2005 recorded an average DMFT value of 0.7 among 12-year-olds, along with an average of 0.9 teeth with initial caries present.22 Our analysis excludes third molars. The periodontal status is assessed using the Community Periodontal Index (CPI), where CPI 0 indicates healthy gums, CPI 1 indicates bleeding, CPI 2 indicates calculus, CPI 3 signifies shallow pockets (4-5 mm), and CPI 4 indicates deep pockets (≥ 6 mm). In this regard, CPI 4 is the most critical value, as it denotes severe periodontal disorder, qualifying this stage as a 'condition of public health concern'.23

… for children and adolescents

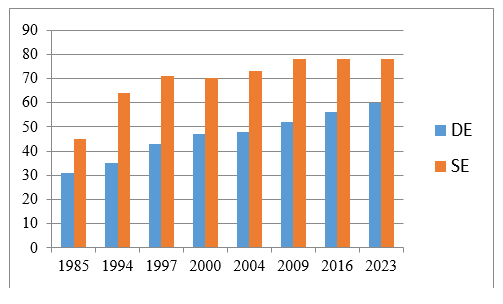

The dental health of the younger generation (ages 0-18) is crucial for establishing sound oral health in adulthood. Therefore, our analysis begins with the trend in the percentage of caries-free primary teeth among 6-year-olds over the past few decades (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Development of caries freedom in 6-year-old children in Germany1 and Sweden2 from 1985 to 2023.

2. The Swedish figures for 2005 are based on 2004 data, while those for 2009 relate to 2010 data, and the 2023 value refers to 2020 data.6\,21,24,25

A consistent upward trend in the percentage of caries-free 6-year-olds has been observed in both countries. The level of cavity-free children is generally higher in Sweden; however, it has stabilised since 2009 at approximately 80%. This suggests that Sweden may have reached its optimal level of caries prevention in young children. In contrast, Germany continues to show improvement, albeit at a lower level.

Regarding caries experience in primary teeth (dmft) among 6-year-olds, long-term data for Sweden is available only from 2011 to 2020.6 Figure 2 illustrates that caries prevalence in both countries is nearly equivalent. Notably, the 2023 value for Germany (1.3) applies to 8/9-year-olds, while the Swedish figure has remained stable at 0.9 since 2016. Additionally, the continuous decrease in dmft among 5-year-old children in Jönköping, Sweden, from 6.5 in 1973 to 1.5 in 20132 further supports this observation.

The next age group of interest is 12-year-olds, as the number of permanent teeth increases significantly after their eruption, peaking around ages 10 to 14.23 Additionally, the first molars, which are particularly vulnerable to cavities, are fully developed during this period, while the second molars are also emerging. The development of caries prevalence, as documented by DMFT, is presented in Figure 3.

In terms of preventive measures for children and adolescents, Figure 3 highlights the significant lag in Germany between 1973 and 1997. However, since then, the legally implemented changes in dental care have proven effective, resulting in comparable oral health outcomes among German adolescents. In the past decade, German DMFT values (0.4-0.5) have even fallen below those of Sweden (0.7). Furthermore, the decreasing Significant Caries Index (SiC) values, measuring the mean DMFT of the third of the population with the highest caries score, in both countries over the last twenty years suggest that preventive dental efforts are also benefitting lower socioeconomic classes in both Germany and Sweden (see Table 1).

|

Country |

1994 |

1997 |

2000 |

2004 |

2009 |

2014 |

2016 |

2023 |

|

DE |

5.3 |

4.5 |

3.4 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

|

SE |

- |

2.81 |

2.62 |

2.93 |

2.44 |

2.15 |

2.1 |

2.26 |

Table 1 Development of the SiC in German and Swedish 12-year-old children from 1994 to 2023

11998; 22001; 32005, 42010; 52015; 62021.6,21,22,28

The long-term decline in SiC values in Germany has been slightly more pronounced than in Sweden, with levels appearing to stabilise over the last decade in both countries. A similar trend can be observed concerning cavity-free adolescents aged 12. Between 1994 and 2023, the percentage of caries-free adolescents increased from 30% to 78% in Germany and from 48% to 68% in Sweden.6,21,28 This indicates that currently, only 22% of German adolescents and 32% of Swedish adolescents require conservative treatment (DMFT >0).

… a short excursion on orthodontics in adolescents

Orthodontic morbidity in adolescents is a significant concern, particularly for those aged 9 to 14,29 as orthodontic misalignments can adversely affect the oral cavity. We will briefly examine the frequency of malocclusions in this age group. Recent epidemiological results for Germany indicate that among 8- and 9-year-olds, the morbidity rate of malocclusions is 40.4%, as measured according to the orthodontic treatment guidelines set by the statutory health insurance provider.29 This magnitude has been consistent with a regional study conducted twenty years ago,30 as well as with a current study in a German orthodontic practice spanning a 20-year period from 2002 to 2022.31

The surveys conducted nationwide in 2023 and in 1989 show nearly identical results for a healthy natural orthodontic dentition (0.7% and 1%, respectively).26,29 This leads the authors to conclude that the normative need for orthodontic care has remained stable over the past thirty years.29 A study involving children aged 3 to 17 revealed that more than half of adolescents aged 13 to 14 received orthodontic treatment per the guidelines established in 2003.32 Trends observed over the past ten years (from 2003-2006 to 2014-2017) indicate a slight increase in new orthodontic cases across all age groups examined, specifically ages 7-10, 11-13, and 14-17.32 However, when considering a longer timeframe, the number of new cases, which totaled about 460,000 in 2023, has remained relatively stable compared to the level recorded in the year 2000.33

Regarding the effectiveness and quality of orthodontic care, a recent cohort study involving multiple centers in Germany - including university hospitals and specialized orthodontic practices - found that 81.5% of adolescents aged 15 achieved high-quality results after an average treatment time of 32 months, with a final Peer Assessment Rating (PAR) score of 5 or lower. This improvement rate indicates a commendable quality standard.34 However, it remains uncertain whether these results reflect the majority of standard orthodontic practices. Additionally, there is a lack of epidemiological data to determine the long-term durability of the treatment results. Furthermore, it is still unclear whether orthodontic treatments in adolescents - except for a few severe malocclusions - positively affect general oral health over the long term. A review study commissioned by the German Ministry of Health concluded that there is no evidence supporting orthodontic benefits on long-term oral health outcomes, such as tooth loss, periodontal disorders, or secondary caries.35 This finding is consistent with an Australian cohort study that found no better oral health in older individuals who had undergone orthodontic treatment.36 Only a large study from Korea indicated that individuals who received orthodontic treatment had significantly fewer untreated caries; however, no correlation between orthodontic treatment and the DMFT score was identified.37

In Sweden, there are no national regulations or guidelines for treating malocclusions, leading each region to establish its own criteria, typically based on a modified International Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN) Index. Orthodontic treatments are publicly funded for children and adolescents up to age 19 if they exhibit an IOTN score greater than grade 4 or 5.38,39 At the beginning of the 21st century, 37% of 12- and 14-year-olds were considered to have "real treatment needs" (grade 4 or 5). Aside from immigration, there has been no change in the need for orthodontic care compared to previous years.39 A 2019 study conducted in Östergotland among children aged 8 to 15 found that 25.7% received specialized orthodontic care.38 Authors estimated that about 25% to 30% of children and adolescents in Sweden receive specialist orthodontic treatment. Notably, adolescents without caries (DFT=0) were more likely to receive treatment than those with a DFT of 1-4 or greater.38 In summary, both Germany and Sweden display similar orthodontic morbidity, though Sweden's treatment frequencies are slightly lower and have remained constant over time as well as those in Germany.

… for adults and seniors

The situation for adults and seniors, particularly middle-aged adults, reveals a different trajectory. In the 1970s and 1980s, DMFT values in both countries were quite high. However, in Sweden, the DMFT values began a notable decline in 1993, resulting in a remarkably low DMFT score of 6.2 by 2020 (Table 2). This positive shift can be attributed to systematic preventive dental activities that commenced in the early 1970s. For Germany, this trend began in 2005 - about a decade later - and led to a DMFT of 8.2 in 2023, reflecting the implementation of strict preventive care measures during childhood and adolescence since the 1980s. Starting from extremely high levels of missing teeth in the 1970s, with an average of 4.8 for both countries, the reduction in tooth loss in Sweden began once again in 1993, reaching a level of 0.8 by 2020. In contrast, Germany's reduction started later and was less intense, halving during the last decade to a missing teeth (MT) value of 1.0 (as shown in Table 2), which indicates that Germany has nearly caught up to Swedish standards. However, since the prevalence of caries in Germany remains higher, its filling activity (FT) is consequently elevated, with values of 6.8 in Germany compared to 5.2 in Sweden.

|

Country |

Indicator |

1973 |

1978 |

1983 |

1989 |

1993 |

1997 |

2003 |

2005 |

2013 |

2014 |

2020 |

2023 |

|

DE |

DMFT |

- |

17 |

17.7 |

17.32 |

- |

16.1 |

- |

14.5 |

- |

11.2 |

- |

8.2 |

|

SE3 |

22.9 |

- |

22.4 |

- |

17.7 |

- |

13 |

- |

7.4 |

7.1 |

6.2 |

- |

|

|

DE |

MT |

- |

4.8 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

- |

3.9 |

- |

2.4 |

- |

2.1 |

- |

1 |

|

SE3 |

4.8 |

- |

3.2 |

- |

1.4 |

- |

1.5 |

- |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

- |

|

|

DE |

FT |

- |

9 |

10.9 |

11.5 |

- |

11.7 |

- |

11.7 |

- |

8.6 |

- |

6.8 |

|

SE3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6.3 |

6.3 |

5.2 |

- |

Table 2 Development of DMFT and MT values in 34/44-year-old individuals from Germany and Sweden,1 1973-2023

140 years,

2After 1989 the subject selection and the definition of caries changed, but had little influence on the results; for example, in 1989 the value after the new methodology was 16.7

3Since 2013, SKaPa data has been used instead of Jönköping data, although the latter were supposed to be representative of the whole of Sweden.2,6,21,22,26,27

Table 3 illustrates the potential impact of preventive treatments for children and adolescents in Germany on oral health in older adult age groups. The oral health of seniors, as measured by DMFT, remained largely unchanged until 2005. However, the first signs of improvement were documented in that year. Since then, the overall morbidity level has dropped significantly, resulting in DMFT values of 17.6 in 2023. Concurrently, the extreme levels of tooth loss have steadily declined since 2005, reaching a value of 8.6 in 2023. Despite this positive trend, German seniors still lose, on average, much more teeth than their Swedish counterparts.

|

Country |

Indicator |

1973 |

1978 |

1983 |

1989 |

1993 |

1997 |

2003 |

2005 |

2013 |

2014 |

2020 |

2023 |

|

DE |

DMFT |

- |

23.0 |

23.2 |

23.0 |

- |

23.6 |

- |

22.1 |

- |

17.7 |

- |

17.6 |

|

SE |

25.6 |

- |

23.8 |

- |

24.4 |

- |

23.1 |

- |

15.1 |

15.0 |

15.4 |

- |

|

|

DE |

MT |

- |

17.8 |

17.8 |

16.2 |

- |

17.6 |

- |

14.1 |

- |

11.1 |

- |

8.6 |

|

SE |

14.7 |

- |

13.9 |

- |

9.9 |

- |

7.3 |

- |

5.6 |

5.2 |

2.9 |

- |

|

|

DE |

FT |

- |

3.7 |

3.8 |

5.8 |

- |

5.8 |

- |

7,7 |

- |

6.1 |

- |

8.6 |

|

SE |

10.5 |

- |

10.4 |

- |

14.4 |

- |

14.1 |

- |

9.43 |

9.6 |

12.2 |

- |

Table 3 Development of DMFT and its MT and FT components in German1 and Swedish2 seniors, 1973-2023

1After 1989, the subject selection changed, but had little influence on the results

270 years

3Since 2013, SKaPa data has been used instead of Jönköping data. The Jönköping data from 1973 to 2003 only reflect filling figures based on surfaces (FS); therefore, we converted FS data into FT data using the assumption that two-thirds of single and two-surface fillings and one-third of three- and four-surface fillings were completed, respectively. Thus, these data are estimations based on actual FS data.2,6,21,22,26,27

Until 1997, filling therapy in Germany was relatively low because prosthetic procedures dominated the dental treatment landscape. After the first positive outcomes of the paradigm shift in dental care in 2005, the level of filling therapy increased to 7.7, eventually reaching 8.6 currently. This illustrates that a preventive and tooth-retaining approach to dental care has also begun to take root in Germany. In Sweden, the disease activity (DMFT) remained high at a level of 23.1 until 2003, then sharply fell to 15.4 by 2020, indicating a significantly lower DMFT level in the country. The differences between the two countries in terms of MT levels have shown more pronounced changes since the 1970s. Sweden made substantial reductions in missing teeth starting in 1993 and consistently progressed in preventing tooth loss into older age. The MT value for 2020 was only 2.9, having been halved in the last six years (as noted in Table 3). Consequently, the Swedish MT level in seniors is currently only one-third (2.9) of the German level (8.6), expanding the gap between the two during the period from 2005 to 2020. This significant finding warrants further explanation.

Different levels of periodontal morbidity in both countries may play a significant role in oral health outcomes. In older adults, particularly those aged 65-74, more teeth are lost due to periodontal disorders than due to caries. Therefore, we focus exclusively on periodontal diseases affecting seniors in this age group. Our aim is to determine whether the prevalence of periodontitis influences the number of missing teeth, the percentage of edentulous seniors and the DMFT within this demographic. We consider the development of severe periodontal disorders, defined as having a periodontal pocket depth greater than 6 mm (CPI Grade 4). This grade is crucial in our context, as it indicates an urgent need for treatment23. Figure 4 illustrates that there is no direct correlation between the DMFT score, the number of missing teeth (MT) and the frequency of edentulism in seniors in relation to severe periodontitis. This means, the relationship between oral health and periodontal destruction remains unclear in Germany. In this context, it might be important to note that the main risk factors for severe periodontitis-such as smoking, diabetes, and Body Mass Index (BMI)—have significantly increased between 2005 and 2023.22,40 This rise may also contribute to the high prevalence of severe periodontitis.

Striking is the high prevalence of periodontitis in the adult population and the sharp deterioration in periodontal health between the age groups of 35-44 years and seniors. In 2023, severe periodontitis increased from 16.2% to 42.4% within this age range,40 representing an increase of one and a half times. This necessitates further investigation into periodontics and its effectiveness from a population perspective. However, the new German guidelines for periodontal treatment, established based on case definitions by the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) and the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and effective since 2021,40 may enhance the quality and effectiveness of treatment. Notably, the inclusion of supportive periodontal therapy in the benefit catalogue of Statutory Health Insurance may increase treatment efficacy in the future and could lead to more positive outcomes in periodontal health.

Unfortunately, there are no segregated CPI 4 values available for Sweden. However, regular cross-sectional surveys conducted among residents of Jönköping every ten years indicate that the prevalence of periodontal pocket depth (PPD) of 4 mm or more in 70-year-olds decreased from 85% to 62% between 1983 and 2013.2 In Germany, the comparable prevalence is 86.4% in 2023.40 Additionally, the percentage of Jönköping subjects without a history of periodontitis improved from 43% to 60% during the same timeframe.41 In contrast, only 8.2% of seniors in Germany show no or mild periodontal signs (CPI 0, 1, or 2).40 These data suggest that periodontal health in Sweden is better than in Germany. From a population perspective, the relationship between caries and periodontal diseases in Germany remains a mystery. This aligns with the views of Eickholz et al.,40 who question the rationale behind classifying a condition as a disease when more than 80% of the population is affected. Similarly, in orthodontics, it has been found that 97.5% of adolescents have a normative medical reason for treatment.29

Regarding filling therapy, and in light of the significant caries activity observed in both countries between 1973 and 2005, it is evident that the Swedish values of filling therapy (FT) among seniors are significantly higher than the extremely low values reported for their German counterparts. This discrepancy highlights the contrasting treatment philosophies during that period: Sweden adopted a strictly preventive and tooth-retaining approach, while Germany leaned towards a largely prosthetic-oriented strategy, which involved numerous extractions and predominantly prosthodontic procedures with minimal filling therapy. As oral health in the Swedish population improved earlier and more intensively, the FT values in Sweden experienced a slowdown from 2013 to 2020. However, they still remained higher than the corresponding German values during that period, primarily because the frequency of prosthetic procedures was still much more pronounced in Germany (see Table 3).

Analysing the cumulative caries experience in the German population from 2000 to 2015, a study documented a clear decline in morbidity, from 1.1 billion DMFT in 2000 to 1 billion in 2005 and 867 million in 2015. The authors projected that by 2030, this number could further decrease to 740 million.42 This signifies a treatment need reduction of nearly one quarter between 1997 and 2015, and a two-thirds decline between 1997 and 2030. It is likely that the decline could be even more pronounced, as the unexpectedly low caries burden levels observed in the DMS 6 survey for 2023 were not factored into this projection. Whether such a shift in (normative) treatment need is reflected in the conservative treatments provided will be analysed later.

The single indicator of 'edentulism in seniors' holds significant relevance as it reflects the effectiveness of a national dental care system over an individual's lifetime. Figure 5 illustrates the development of total tooth loss over time, revealing that between 1997 and 2005, edentulism among German seniors remained stagnant. Since 2014, this rate has nearly halved to 12.4%, and then further reduced to 5% in 2023. In Sweden, the trend started from a notably high level of 45% in 1980/81, decreasing sharply until 1996/97, and then experiencing a steadier decline to 2.5%, half the rate seen in Germany.

The Dental Health Index (DHI) is a comprehensive metric that assesses the dental health of an entire population. This index enables us to quantitatively evaluate the changes in oral health status over time. The DHI is calculated using the following formula: DHI = (Caries-free Index 5/6 + DMFT 12 + DMFT 35/44 + MT Index 65/74 + Edentulism Index 65/74) / 5. A lower DHI score indicates better oral health status.45 Figure 6 illustrates the development of the DHI over the past decade. In the last ten years, the oral health status of citizens in Germany improved from a DHI of 4.5 to 3.6, representing a 20% improvement. Although Sweden began with a lower initial DHI, its population experienced an even greater enhancement, achieving a 28% improvement over the same period.

The significant improvements in oral health across the entire population have been accompanied by adequate patient cooperation. Key requirements for this improvement include proper domestic oral hygiene and regular dental visits focused on preventive care. After the introduction of systematic prophylactic measures for children and adolescents in the 1980s, the first positive effects on oral hygiene behaviour and the utilization of dental services were documented in the German DMS Survey of 1997. Subsequent DMS Surveys have indicated a consistent improvement in tooth brushing habits and dental attendance patterns. However, as of 2023, the effectiveness of plaque removal is suboptimal, with nearly half of tooth segments across all age groups showing persistent plaque deposits.46 This indicates a need for enhanced toothbrushing skills among the general population. Additionally, the fact that in 2018 two-thirds of socially insured patients who undergo crown or prosthetic procedures utilise a bonus option,47 highlights the effectiveness of this monetary incentive. This incentive is granted after five years respectively 10 years of continuous annual dental check-ups, aimed at encouraging regular dental visits. These statistics reflect the high attendance rates for dental care in Germany.

In conclusion, based on these epidemiological findings, it appears that, compared to Sweden - our benchmark country - Germany has made progress in addressing the earlier backlog in oral health among its citizens, particularly within the younger age groups. However, the overall oral health status of the Swedish adult population remains superior. Nonetheless, particularly following the release of the latest German survey data from 2023, which exceeded expectations, it is clear that Germany is on a promising path towards achieving the goals projected for 2030 earlier than anticipated.42,48,49 The extent to which the long-term epidemiological evaluations for Germany align with the evolving dental treatment structures will be explored in the following chapter.

Long-term treatment structure analysis

Two primary data sources provide the necessary treatment data for this analysis: the regular yearbooks of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists (KZBV)33 and, since 2011, the annually published reports from a major German statutory health insurance fund (Barmer Health Insurance). The structure of its insured persons is considered to be approximately representative of the entire German insured population and allows for further sociodemographic analyses of utilization and service users.47 Additionally, it facilitates investigations into age cohorts and longitudinal studies, which are crucial for understanding questions related to cause and effect.

The nationwide prophylactic system for youth up to age 18 consists of three components. The first component is basic group prophylaxis, which also includes intensive prophylactic activities for high-risk groups. It was introduced in 1989. This programme is conducted in kindergartens and schools, covering children aged three to twelve years, and, since 2000, it has also extended to adolescents up to age 16 who have a disproportionately high risk of caries. This is the most comprehensive preventive service available, benefiting also in particular disadvantaged children and adolescents. The programme is run in collaboration with the public dental service, settled dentists, and statutory health insurance funds, and it is largely financed by these health funds. In 2019, approximately €50 million was allocated to these activities.50 Nearly 80% of children and adolescents participate in these programmes, which are typically held several times a year.51 The second component of the preventive system is individual prophylaxis. This aspect of the programme covers individuals aged 6 to 18 years and is provided by settled dentists. The third component consists of three early detection examinations for toddlers from the 6th month to the 33rd month. and since 2019, three additional examinations have been included for children from the 34th month to the end of their 5th year. Together, these components create a comprehensive preventive concept for Germany's youth up to age 18.

An overview of the core utilization rates concerning prevention and tooth retention from 2010 to 2018 is presented in Table 4. Total utilisation rates include diagnostic and counseling measures, which are essential in nearly all cases. Over time, these procedures remained stable at slightly above 70%, a comparatively high level in an international context.47 Fillings have steadily declined from 29.6% in 2010 to 26.5%. The use of panoramic X-ray images showed minor but continuous utilization rates, possibly indicating diagnostic improvements in treatment quality. Root canal fillings, which are used to save severely endangered teeth, showed a slow decline from 6.4% in 2010 to 5.3% in 2018. This decrease could be attributed to the general reduction in caries experience within the population. Consistent with the declining rates of filling and root canal treatments between 2010 and 2018, tooth extractions also diminished from 9.5% in 2010 to 8.3% in 2018. These trends align tendencially with the improvements in oral health observed across all age groups.

|

Type of procedure |

2010 |

2014 |

2018 |

|

Total utilization |

70.5 |

71.3 |

70.2 |

|

Fillings |

29.6 |

28.8 |

26.5 |

|

X-ray panoramic slice image |

8.7 |

9.2 |

9.6 |

|

Root canal treatment |

6.4 |

6.0 |

5.3 |

|

Extractions |

9.5 |

9.0 |

8.3 |

|

Periodontal dagnostic and therapy |

24.61 |

24.6 |

26.9 |

|

Early detection examinations (children <6 years) |

31.9 |

33.9 |

35.2 |

|

Individual prophylaxis (6 to <18 years) |

64.0 |

64.5 |

65.4 |

Table 4 Yearly utilization rate (%) of core tooth retaining treatments from insured individuals of the Barmer Sickness Fund, 2010-2018

1Value is for 201247

Periodontal diagnostic and therapeutic procedures increased slightly from 24.6% in 2014 to 26.9% in 2018 (Table 4). However, this utilisation rate remains significantly lower than the normative treatment needs identified in surveys and is only about half of the theoretical treatment rate that statutory health insurance would cover.47 Considering the high morbidity rates of severe periodontitis reported in the 6th DMS survey,40 the treatment statistics and periodontal health appear to be diverging. The situation may improve, as the periodontal guidelines were modernised in 2021 to include measures for supportive periodontal therapy or maintenance. Nonetheless, periodontology in Germany still raises numerous questions that finally require clarification.

Early detection examinations for children under the age of 6 increased from 31.9% in 2010 to 35.2% in 2018. Additionally, individual prophylaxis rates for children aged 6 to under 18 were relatively high, averaging around 65% throughout the eight-year period.

A longitudinal cohort study conducted over nine years revealed that from 2012 to 2020, the proportion of insured individuals aged 20 without invasive services was relatively high at 23.7%. For those aged 40, the share was less than half at 11.2%, while the cohort aged 60 had a rate of 11.6%.52 This indicates that during middle age, the least number of people can avoid invasive treatments. The therapy-free periods were 3.9 years for 20-year-olds, 1.7 years for 40-year-olds, and 1.5 years for 60-year-olds, highlighting a clear trend towards extended therapy-free periods in the younger and middle-aged cohorts.52 The trend towards longer intervals without invasive therapy underscores the ongoing shift towards preventive dentistry in Germany.

A similar trend has been observed in Swedish social insurance (Socialstyrelsen), where from 2014 to 2023, the time between baseline examinations for the population aged 24 and older has consistently increased, while a lower proportion of these individuals received invasive treatments. In 2023, only 31% of the examined patients underwent invasive treatment within six months of their examination, down from previous years.53

Furthermore, billing data from the KZBV demonstrates a significant shift in the relationship between tooth retention and prosthetic procedures over time (Figure 7). In the 1970s and early 1980s, the percentage of tooth retention sharply declined from over 60% to less than 50%. A turning point occurred in 1982 when a legal paradigm shift in dentistry (1978-2000) commenced. Since then, the percentage of tooth retention has progressively increased, while the share of prosthetic treatments has significantly decreased. This intended development aligns with the gradual improvement in oral health, first observed in the younger generation and later among adults. The period between 2020 and 2023 may indicate a slowdown in this ongoing shift but it is too early to interpret this.

In the following chapter we shed particular light on the period from 2000 to 2023, because epidemiological surveys from this timeframe indicate the first consequences of improving oral health among younger adults. The most relevant areas of treatment include conservative and surgical procedures, which have become increasingly dominant since 2015 (Table 5). This trend aligns with the positive developments in oral health across all age groups. Alongside this trend of prioritising tooth retention in Germany is a modest increase in periodontal measures. However, the positive impact of periodontics has been smaller than anticipated, as noted in our reflections on periodontal topics above. It remains unclear how the recent inclusion of supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) in the periodontal guidelines will affect this situation. It is evident that there is a strong trend for a long-term decline in prosthodontic procedures, driven by improving oral health and evolving treatment demands. Compared to the year 2000, the number of prosthetic treatment cases has decreased by more than one third (Table 5).

|

Treatment field |

2000 (in thous.) |

2005 (in thous.) |

2010 (in thous.) |

2015 (in thous.) |

2020 (in thous.) |

2023 (in thous.) |

|

Conservative and surgical |

88,197 |

82,557 |

84,823 |

92,356 |

88,773 |

96,678 |

|

Periodontal |

732 |

815 |

954 |

1,041 |

1,041 |

1,129 |

|

Prosthetic |

12,274 |

10,090 |

10,283 |

9,566 |

7,974 |

7,737 |

Table 5 Settled cases in different treatment fields of statutory health insurance in Germany, 2000-202333

Now, we will take a more detailed look at the conservative sector in a narrower sense. The data for this examination is presented in Figure 8. It is noteworthy that smaller fillings (F1-2) account for about 70% of total fillings, while three- and four-surface fillings (F3-4) make up the remaining 30%. Both types of fillings have decreased more rapidly and stronger than root canal fillings, whereas extractions have shown a slower and more moderate decline. Between 2020 and 2023, extractions appeared to increase slightly. This is difficult to interpret, particularly because this period was heavily influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, the overall decline in both smaller and larger fillings, and – to a smaller extent - in root canal treatments, has reached reductions of 30%, 25% and 10%, respectively over the past twenty years (Figure 8). This decline roughly corresponds with the epidemiological findings of decreased caries experience among individuals aged 6 to over 90 between 2000 and 2015, amounting to a reduction of 20%.42 When a large-surface filling cannot stabilise a severely damaged tooth, a crown can serve as an alternative to preserve the tooth and prevent extraction. On the other hand, crowns may also function as part of a denture. This dual role of crowns makes it difficult to differentiate their use in statistical data. However, since they are primarily used for tooth retention, and when functioning as part of a denture, they also are intended to support a complete dentition, we, here, assume that all crowns placed serve the purpose of tooth retention. Remarkably, the provision of crowns exhibited a significant upward trend between 2005 and 2010, which remains challenging to explain. From 2010 onward, the frequency of crowns placed has gradually decreased, mirroring the trend observed with filling treatments. This trend is as well consistent with the broader epidemiological development in the whole population during 2000 and 2015.42

The relatively modest reduction in extractions, which stands at 12% since 2000, is indicative of the still high number of missing teeth among adults over 40 years of age.33

In terms of prosthetic provision, the ongoing decline in tooth loss among individuals aged 35 to 44 has led to a decrease in the prevalence of removable dentures within this age group as of 2023. Meanwhile, seniors have seen a rise in the use of combined fixed and removable dentures, which is a positive development due to their superior comfort and longevity. Despite the high satisfaction levels reported by seniors using removable dentures, with a continuous wear rate of 40% needing restoration measures, there were only complaints regarding simple acrylic dentures.54 In the middle-aged category (35-44 years), the most invasive and expensive prosthetic option - dental implants - has seen significant growth, doubling from 3.4% in 2014 to 7.1% in 2023. These dental implants are primarily used for anchoring fixed dentures. For seniors, the frequency of dental implants nearly tripled from 8.1% in 2014 to 23.2% in 2023. Similarly, in this age group, implants were predominantly utilised for anchoring fixed dentures.54

A summary of the long-term changes in treatment practices indicates a clear shift in focus from prosthodontics to prevention and tooth preservation in Germany. This transition is ongoing. However, despite notable successes, a majority of supply events are still dominated by invasive therapies, which are favoured within the social fee system. To further promote the shift towards preventive and non-invasive measures, Walter and Rädel suggested that the value relationship of the Uniform Fee Schedule for Dental Services (BEMA) should be adjusted to prioritise preventive and less invasive treatments.47

Long-term total dental cost analysis

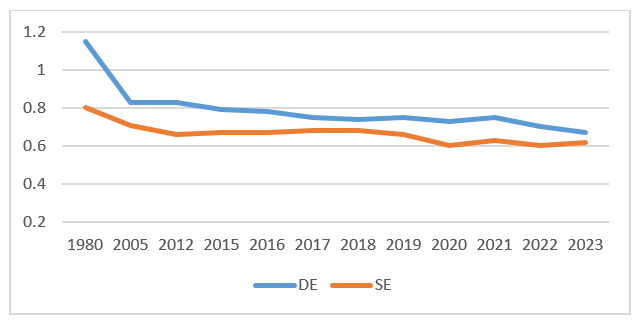

When the paradigm shift in German dental care was gradually implemented from 1978 to 2000 and onwards, the expectations were twofold: firstly, to improve oral health by transitioning from a prosthetic to a preventive and tooth retention-oriented approach, and secondly, to save macroeconomic resources in the medium and long term. Whether these assumptions have been achieved is now under review, as outlined in Figure 9.

Figure 9 Development of total dental costs in percentage of GDP in Germamy and Sweden, 1980-2023.55

In 1980, Germany spent 1.15% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on dental care financing. These data reflect the comprehensive financial burden of oral care, including out-of-pocket expenses and the total costs of privately insured individuals, allowing for a comparative analysis of different dental care systems, regardless of provider types (private, public, or a combination of both) and financing methods. During the implementation phase of the new system (1980-2005), oral health slowly improved, and the macroeconomic cost level significantly decreased to 0.83% of GDP in 2005. With ongoing advancements in oral health, financing needs for dental care gradually dropped further to 0.67% by 2023. This represents a dramatic increase in cost efficiency for the dental sector, amounting to nearly 60% over the course of 45 years. Consequently, the earlier health policy expectations of improving oral health and, subsequently, reducing overall dental expenditures have largely been realised.

The example of Sweden, which implemented a similar paradigm shift in dentistry more than a decade earlier, corroborates the German outcomes in both benefits and costs. With relatively better oral health, Sweden has managed its dental care system with fewer resources compared to Germany. In 1980, Sweden's dental care costs were at 0.80% of GDP and decreased until 2023 to 0.62%, meaning that Germany is approaching Swedish cost standards. This Swedish data as well support the conclusion that a preventive and tooth retention-oriented approach in dentistry not only enhances oral health but also lowers necessary relative macroeconomic expenses. Considering that Sweden's oral health is already highly advanced, only minimal progress is expected in the future. This suggests that dental care costs may stabilise around 0.6%.

Meanwhile, Germany still has opportunities to further improve oral health, which could lead to additional reductions in relative costs. Furthermore, similar high-income countries with advanced dental care systems typically allocate financial resources for their dental care sectors ranging from 5% to 6% of GDP.55,56

Our findings revealed that the oral health of children and adolescents in Germany has largely reached the low caries burden observed in Sweden. In 12-year-olds, this even falls below the minor DMFT values seen in Sweden. However, there is still room for improvement, especially regarding the proportion of caries-free primary teeth. This improvement could be facilitated by the German modified guidelines for early detection examinations for children up to age 6. Starting in 2026, pediatricians and dentists will document their examinations uniformly in the well-established "Yellow Booklet" for children. This will help parents better understand the importance of precautionary dental appointments, making dental visits as routine as regular medical visits. Furthermore, early childhood caries can be more easily prevented, and collaboration between pediatricians and dentists may be enhanced.57

The examination of orthodontic treatment among adolescents aged 9 to 14 highlights significant morbidity rates and a high demand for treatment, particularly among 13- and 14-year-olds, where about half of these age groups receive treatment. However, it remains unclear whether these orthodontic interventions have a lasting positive impact on overall oral health, as there is limited evidence available. This raises the question of the validity of stating that 97.5% of these age groups have medical reasons for orthodontic treatments, like it is reported in the DMS 6 study.

German adults aged 35 to 44 have made significant progress in reducing their caries burden and the prevalence of missing teeth over the past two decades, thereby narrowing the gap with Sweden. These improvements are likely a result of preventive measures that this age group benefited from in their youth. However, greater discrepancies in oral health persist between German and Swedish seniors. The lack of preventive activities among today's 65 to 74-year-olds might have contributed to this issue.58 Although German seniors have dramatically reduced their caries experience and missing teeth rates in the last decade while increasing their filling rates, stark differences remain compared to Swedish seniors. On average, German seniors lose three times as many teeth (8.6) as their Swedish counterparts (2.9), and the differences in edentulous seniors are similarly pronounced. Despite robust reductions in edentulism since 2005, which reached only 5% in 2023, this rate is still double that of Sweden (2.5%).

In this context, Germany faces challenges regarding periodontal health, as there is a high burden of severe periodontitis among individuals over 40 years of age. From this age onward, individuals tend to lose more teeth due to severe periodontitis than as a result of cavities. Therefore, the hypothesis that this phenomenon contributes to high tooth loss rates in older age groups in Germany seems plausible. On the other hand, although approximately 80% of German seniors in 2023 are affected by moderate to severe periodontitis, tooth loss among this group has decreased remarkably from 11.1 in 2014 to 8.6 in 2023. This decline coincided with a period when 40% of seniors were suffering from severe periodontitis, presenting a paradox that needs further investigation. It suggests either that the measurement of periodontitis is inadequate, or that treatment methods are insufficient. Perhaps the modernised German periodontal guidelines, which have been in effect since 2021, may help clarify this issue in the future. Another possibility is that the threat to natural teeth posed by periodontal diseases is less severe than periodontal theory suggests, indicating that the direct relationship between caries and periodontal disorders is not fully understood.

Overall, with the exception of orthodontic and periodontal procedures, treatment approaches have evolved in response to the significant epidemiological progress regarding the retention of natural teeth among the population. A remarkable transformation has occurred, shifting from a focus on prosthetic treatments to a predominance of conservative therapies. Additionally, there is a positive trend in prosthodontics: the use of removable dentures among middle-aged individuals is minimal, and among seniors, the combined use of fixed and removable dentures has become the norm.

With respect to the relative costs of dental care in Germany, there have been substantial reductions since 1980. According to OECD statistics, no other country with an advanced dental care system can claim such a remarkable achievement.55 Notably, this reduction occurred alongside great improvements in the population's oral health status. Other than vaccinations, there may, over time, not be many health fields that have achieved such efficiency gains. In other words, a preventive and tooth-retaining approach that incentivises dentists, patients, and health insurance funds is also economically valuable from a societal perspective. A similar correlation can be observed in Swedish dental care, which strengthens the argument for a well-designed preventive and tooth-retaining strategy from childhood to adulthood. Comparable relationships over thirty years are also reported from Denmark.55,59 In summary, the overarching result of our extensive long-term study, which spans 50 years of dental care in Germany and Sweden, shows that a dental care system focused on prevention and tooth retention yields better outcomes in both oral health status and cost-effectiveness.

Although our study encompasses a substantial volume of data, the design does not permit us to establish causal factors. Instead, we are able to describe development processes, identify changes and trends over time, and illustrate relationships. Nevertheless, the combined analysis of longitudinal epidemiological and treatment data over a period of five decades represents a significant strength, which is a rarity in the field of dental science.

Despite significant long-term progress in oral health across all age groups and substantial improvements in cost efficacy in Germany, there are still a few areas in dentistry that require enhanced attention. These areas of concern include:

As a consequence of our key finding, the author suggests that the principle of 'priority for prevention and health maintenance' should also be adopted in appropriate areas of general medicine.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Saekel. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.