Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 16 Issue 4

1São Francisco University, Brazil

2Taubaté University, Brazil

3University of São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence: Miguel Simão Haddad Filho, Professor of Dentistry at the University of São Francisco, Bragança Paulista SP, Brazil

Received: September 10, 2025 | Published: October 6, 2025

Citation: Filho MSH, Simões ALM, Ramos HRB, et al. Microorganisms present in PRP® medication tubes used in endodontic treatment. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2025;16(3):147-155. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2025.16.00658

Intracanal medication is an essential step in endodontic treatment, playing a crucial role in the disinfection of the root canal system and the modulation of the inflammatory response. Among the available therapeutic options, the combination of Paramonochlorophenol, Rinossoro, and Polyethylene Glycol (PRP®) stands out as the drug of choice in cases of pulp necrosis. However, its commercial presentation in 1.8 mL tubes, often shared among multiple patients, raises concerns regarding compliance with biosafety principles. Given this context, the present study conducted the collection and microbiological analysis of PRP® samples used by students during endodontic procedures. The results revealed the presence of microbial contamination, indicating a possible failure in asepsis protocols. These findings suggest potential risks to clinical safety, reinforcing the need to review current practices for handling and storing this medication. Therefore, it is concluded that the shared use of PRP® tubes may represent a cross-contamination vector, requiring the implementation of stricter control measures or the adoption of individual dosing systems to ensure the safety of both patients and healthcare professionals.

Keywords: endodontic, intracanal medication, cross-contamination, biosafety

Silva Júnior et al.,1 using unused anesthetic tubes, investigated presence of gram-negative bacilli, gram-positive staphylococci, and fungi, finding these colonies in 25 of the 38 samples examined. The authors observed that the infection originated from the tubes' rubber and metal covers, which were improperly stored and transported. Another finding in study indicates during procedures involving the use these tubes, puncture of the cap by the needle would allow microorganisms to enter the anesthetic fluid, resulting in infections during administration.

Lemos2 Intracanal Medication/MIC-endo-e. comments that the function of intracanal medication in endodontics is basically to combat microorganisms that resisted the sanitation of the root canal system provided by chemical-surgical preparation, modulating the inflammatory reaction that occurs after root canal preparation, physically occupying the canal space, as it is known that the empty canal functions as a test tube for microbial recontamination. The action of intracanal medications (MIC) will be conditioned by the vehicle used (aqueous, viscous, or oily); concentration; surface tension in the root canal; and the duration between sessions during endodontic therapy. However, MICs that use an aqueous vehicle have a medicinal action for up to 10 days, viscous vehicles for up to 30 days, and oily vehicles for up to approximately 60 days, directly interfering with rapid, slow, and long-term dissociation, depending on the particular need. Intracanal medications can also be provided in tubes or syringes with sterile cannulas for ease of use. For teeth with mortified pulp, antimicrobial compounds such as calcium hydroxide and paramonochlorophenol are primarily used. In cases where root canal preparation has not been completed for various reasons, such as time constraints, professional skill, etc., paramonochlorophenol combined with polyethylene glycol 400 (viscous vehicle) and rhinosorbit, known as PRP® (FOUSP), is used as an intracanal medication. This medication is also commercially available in tubes. Composition: Paramonochlorophenol (2.0g) Polyethylene glycol 400 + Rhinossoro (qsp) in equal parts (100ml). Initially, the root canal is dried with large, medium, and fine-gauge cervical cannulas to near the working length (CRT or CT), without the need to calibrate the cannulas' lengths with limiters. Afterward, it is dried with absorbent paper cones. We prefer packaged and previously sterilized absorbent paper cones of the same caliber and length as the instrument used in the apical preparation. Using the Carpule syringe and a pre-positioned PRP® tube, calibrate a short, pre-curved needle and silicone stopper 2 mm short of the CRT. It is important to note that pre-curvature can be achieved using, for example, an aspiration auger or a high-speed handpiece to facilitate the introduction of intracanal medication into the canal. Fill from apical to cervical to the vicinity of the canal entrance.

Nassri et al.,3 evaluated antimicrobial action two substances NDP and PRP used as intracanal medication in endodontics, when in contact with bacteria commonly found in the oral microbial flora, Streptococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), in solid and liquid culture media using BHI medium, corresponding to 0.5 on the McFarland scale. For the solid medium, the experiment was carried out in two layers of culture medium on a petri dish. Ten milliliters of Müller-Hinton medium were placed at the base and, after solidification, another 10 milliliter layer was prepared with an infusion of bacteria diluted in 1,000,000 BHI medium and 5 milliliters (ml) of Müller-Hinton, giving a final concentration of 15x100,000 CFU/ml. Filter paper discs previously soaked in the test substances, saline as a negative control, and ampicillin as a positive control, were spread on the Petri dish. For the liquid medium test, 2 ml of BHI medium was placed in tubes with a mixture of 5 ml of bacterial infusion and BHI, previously prepared at a final concentration of 5 x 100,000 CFU/ml. Only one paper disc was placed in each tube. The plates and tubes incubated oven at 37°C 24 hours. Inhibition zones formed when PRP and NDP were used. PRP® showed larger inhibition zones, indicating greater antimicrobial potential. In liquid medium, bacterial growth was observed in all tubes.

Ricucci and Siqueira4 found that in teeth with apical periodontitis, the prevalence of intraradicular bacterial biofilms is high, and extraradicular biofilms are rarely seen, leading to intraradicular infections. Structurally, the endodontic microbiota is arranged in the form of biofilms attached to the dentinal walls of the main canals, lateral canals, apical branches, and isthmuses. Bacteria from the biofilm invade various depths in the dentinal tubules or even detach from the most superficial layers, forming bacterial aggregates suspended in the root canal lumen.

Rocha et al.,5 analyzed the antimicrobial activity of camphorated paramonochlorophenol (PMCC) by direct contact and vaporized against Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus used agar diffusion method. Ten extracted human teeth (canines and premolars upper and lower) were transfixed to Petry dishes with self-curing acrylic resin, so that the dental crowns were above the lid of these dishes. A glass cylinder measuring approximately 5 mm diameter and 1.5 cm height was stick around the root apices. Direct contact test performed with filter paper discs soaked in 3 µL of PMCC placed directly on the culture medium inoculated with the microorganisms. For the vapor test, the PMCC was placed inside the canal with a cone of absorbent paper #40, where it remained for 24 hours. The results revealed that the drug exhibited antimicrobial activity after direct contact with the cultures, forming bacterial inhibition zones. Regarding the vapors released by the product, it was found that there was no vapor action when the drug was in the root canal, as bacterial growth occurred near the root apex.

Haddad Filho et al.,6 emphasize that significant improvements have been made in providing a higher level of safety to our patients and the entire health promotion team, thanks to increasingly comprehensive, strict, and reliable biosafety protocols. To this end, an arsenal of resources is employed to maximize microbial control. Therefore, dentistry programs invest heavily in systems that enable such control; the continued assertion of knowledge, training that implements protective barriers, which allows for risk-free care and, consequently, develops responsibility for disease prevention at all levels of care, under the close monitoring of these practices by educators. However, negligence still persists regarding consumables stored in plastic cases with dividers, carried by students. This study aimed to investigate the microorganisms present in students' cases. Materials and methods: Eighty samples collected from dental cases were analyzed, divided into groups of 20, from four universities, one state university, and three private universities. The collected material was isolated on MacConkey agar and blood agar with sodium azide culture media. Results: Gram-positive cocci, beta-hemolytic, alpha-hemolytic, and gamma-hemolytic bacteria, were identified in seven samples; Gram-negative bacilli and enterobacteriaceae were identified in five samples; and coliforms were identified in three samples. Conclusion: Microorganisms were identified in all academic dental cases and should be adequately disinfected to prevent the spread of bacteria, especially fecal and pathogenic microorganisms.

Haddad Filho7 confirms that it is essential, especially in cases of apical periodontitis, to adopt resources that ensure the effective burial of toxins originating from microorganisms, as well as the bacteria themselves. Therefore, the choice of intracanal medicament is a complementary method whose purpose is to promote healing of the affected tissues by reducing the microbial load and eliminating it. This solution should be used after disinfectant penetration or partial instrumentation of the root canal when the presence of bacteria is suspected. Therefore, in cases of dead pulp or even retreatment before canal preparation, after odontometry and emptying, when canal preparation is not completed for various reasons such as time, professional skill, or persistent doubts about the quality of the root canal disinfection. The indicated solution is PRP® as an intracanal dressing, its composition being paramonochlorophenol associated with polyethylene glycol 400 (viscous vehicle) and rhinosor, called PRP® (FOUSP), also commercially available in tubes. Composition: Paramonochlorophenol 2.0g Polyethylene glycol 400 + Rhinossoro in equal parts qsp 100ml (Intracanal Medication/MIC - endo-e).

Gavini8 comments that although mechanical instrumentation and irrigation play a significant role in bacterial reduction, they are not sufficient to eliminate microorganisms root canal system. He suggests use intracanal medication to complement the antibacterial effects of chemical-surgical preparation. Therefore, in cases of persistent exudation and in occasions where the canal has not been fully instrumented, a combination of calcium hydroxide and paramonochlorophenol is recommended. This can be found as a commercial product or prepared at the time of use using PRP® (Paramonochlorophenol 2g in a 400 wt. polyethylene glycol vehicle/Rinossoro) as the paste vehicle.

Mendes and Vilarino9 explained that anesthetic solutions are used in dentistry to block nerve impulses. A tube is a storage device for anesthetic solutions and is usually found on the dentist's clinical table. Therefore, its external surface must be aseptically cleaned. This study aimed to determine whether microorganisms are present on the external surface of anesthetic tubes used by dentistry students at Fapac/Itpac – Porto Nacional. Ninety anesthetic tubes were collected and analyzed, divided into three groups: Group 0 (control group) (n=90); Group I (multidisciplinary clinic I) (n=30); Group II (multidisciplinary clinic II) (n=30); and Group III (multidisciplinary clinic III) (n=30). For collection, sterile swabs were used, and samples were collected by rubbing the surface of the tubes and then inoculated in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) culture medium for 24 hours in an incubator at 37°C. Subsequently, the four cultures were visually inspected, and microbial growth was determined the presence or absence of turbidity the broth. Microbial growth was observed in three groups; however, highest microbial growth occurred in group 3 (28.9%), followed by group 2 (26.6%), and group 1 (5.5%). Microbial growth was observed in all three groups; however, group 3 (multidisciplinary clinic III) had the highest contamination rate, possibly due to the storage tubes being exposed to contamination for long periods after opening the box and being improperly stored by dental students.

Medinger10 reported dental professionals are exposed daily to large number of microorganisms, therefore they need biosafe techniques in order to minimize the risks of cross-infection, especially that do not allow the autoclave sterilization process, thus requiring chemical agents to assist in the disinfection of the clinical environment. They investigated effectiveness of chemical agents in disinfecting anesthetic tubes through an in vitro study in dental surgical procedures, using following chemical agents: 70% alcohol, 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution (0.12% CA), 2% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution (2% CA), 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution (0.5% CAL), 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), and 10% PVPI (povidone-iodine). Used a control group, in which plastic and one glass tube were not disinfected. The remaining tubes underwent a friction disinfection process for one minute and were kept on sterile gauze until the chosen agent dried. One plastic and one glass tube were used for each of the agents. The swab was then collected by rubbing it over the surface of the tube and inoculated into a Petri dish containing Mueller Hinton culture medium, using the streaking technique. The plates were incubated in oven at 37°C 48 hours, after colony-forming units were counted. The results showed that the tubes that did not undergo the disinfection process had a higher number of microorganisms growing compared to those that were previously disinfected, with 70% alcohol producing greater bacterial colony growth. The most effective chemical agents were PVPI (povidone-iodine), 2.5% sodium hypochlorite, and 0.12% chlorhexidine. Concluded that pre-disinfection of anesthetic tube was necessary. Among the agents tested, PVPI (povidone-iodine), 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and 0.12% chlorhexidine were effective friction method.

Dutra et al.,11 observed during dental care, patients may be exposed various sources of contamination, and so the dental team must always implement biosafety measures. Non-autoclavable materials, such as anesthetic, need to be disinfected before use because they are not sterile and can transmit pathogens between patients. This study aimed evaluate and compare the effectiveness of three disinfectant solutions reducing the microbial load dental anesthetic tubes. The anesthetic tubes (n = 31) were randomly selected and subjected different disinfectant methods and agents (70% alcohol, 7% chlorine dioxide; 5.2% benzalkonium chloride with 3.5% polyhexamethylene biguanide). After disinfection immersion or friction methods, the tubes were plated in culture medium containing trypticase soy broth and incubated (48 h/370C). Samples of the liquid culture medium were subcultured and plated on trypticase soy agar, incubated for 48 h at 370C. Microbial growth was observed the presence of colony-forming units (CFUs) grown on agar. Concluded that 70% alcohol and 5.2% benzalkonium chloride with 3.5% polyhexamethylene biguanide were more effective eliminating the microbial load the tubes using the friction method, and that the anesthetic tubes did indeed have their external surfaces contaminated. The study demonstrated the friction method in disinfecting the agent was more effective in reducing the microbial load compared to immersion. The tested 7% Chlorine Dioxide did not demonstrate a satisfactory level of disinfection.

Jara et al.,12 in vitro investigated antibacterial efficacy of Ca(OH)2 with iodoform versus Ca(OH)2 with camphorated paramonochlorophenol as medication intracanal pastes in an Enterococcus faecalis biofilm used the diffusion method. The strain used was E. faecalis ATCC 29212. Bile esculin agar was inoculated 60-well plates of 5 mm in diameter. Three groups were formed: Group 1: Calen PMCC (Ca(OH)2 + camphorated paramonochlorophenol); Group 2: Metapex (Ca(OH)2 + iodoform); and Group 3: camphorated paramonochlorophenol inoculated with E. faecalis as a positive control. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial inhibition were read. Group 1 be revealed the highest antimicrobial efficacy with a mean of 16.2 ± 0.6 mm and Group 2 had only an antimicrobial effect of 9.7 ± 1.3 mm. Finally, Group 3 only to the positive control (camphor paramonochlorophenol) showed an effect of 14.6 ± 1.0 mm. Inferential analysis showed statistically significant differences between the antimicrobial effect of the three groups (p=0.001). Concluded that Ca(OH)2 paste with camphor paramonochlorophenol (Calen PMCC) has a greater antibacterial action against E. faecalis. Ca(OH)2 paste with iodoform (Metapex) showed significantly lower antibacterial action against E. faecalis (p<0.05).

Jesus and Câmara13 explained that biosafety measures, prevention, and protection against occupational hazards in dentistry are employed in undergraduate programs. The seriousness of these rules became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this descriptive study, they proposed an evaluation of biosafety as a curricular element in Brazilian dental schools, whose population consisted of coordinators of undergraduate dentistry courses in Brazil and an online questionnaire sent between November 2019 and February 2020. The descriptive results indicate that of the 68 courses that responded, 43 had a specific biosafety course, all mandatory, five theoretical, and 38 theoretical-practical. In fact, the more extensive syllabus in courses with a specific course predominated, with topics related to infection prevention and control. Ideally, a specific biosafety course should be included in the curriculum, mandatory in the first year, with reinforcement of the topic throughout the course, especially in courses with practical activities.

Silveira et al.,14 confirmed the emergence of microorganisms resistant to commercial antibiotics and/or disinfectants poses a threat to human health. Therefore, the development of alternatives can be used combat microorganisms is great importance. The action of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) microbiological elimination stands out. This development of microbial resistance due multiple known mechanisms which eliminate microorganisms. The use of AgNPs is still limited due difficulty of synthesis, stabilization, and production costs. Therefore, use of common disinfectants based on quaternary ammonium salts has been preferred. Study, a rapid synthesis of AgNP solution was developed by co-precipitation using sodium citrate as reducing agent. The obtained nanoparticles were characterized by ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering. The spectra showed an absorbance peak at 420 nm, indicating low aggregation suspension. Dynamic light scattering analysis indicated nanoparticles with an average size of 40 nm. The antimicrobial activity AgNP solution obtained was determined by formation of growth inhibition zone using strains Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. A comparison with a quaternary ammonium-based disinfectant showed that AgNP solution is potential alternative for surface disinfection.15

Haddad Filho et al.,16 aimed of present study was to analyze the disinfectant capacity three chemicals used in endodontic treatment on an aggressive microorganism species. The methodology applied was experimental laboratory study to compare the antimicrobial potential of 1% sodium hypochlorite, 2% chlorhexidine, and 17% silver nanoparticles, used endodontics against the pathogen E. faecalis. Nanoparticles were selected the microorganism bank of Molecular and Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Graduate Program in Health Sciences at the University of São Francisco. Their storage use were previously authorized by the University of São Francisco's Research Ethics Committee. After data collection, results were verified and concluded the 2% chlorhexidine solution presented the best results in terms of antimicrobial efficacy compared 1% sodium hypochlorite solution, followed by 17% silver nanoparticles. The latter failed to form a growth inhibition zone against E. faecalis in vitro.

Queiróz and Carvalho17 aimed to analyze the presence of contamination in anesthetic tubes and evaluate the effectiveness of different chemical disinfection agents. Six tubes were collected and immediately inoculated into sterile Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium, followed by incubation. The tubes were then subjected to immersion and friction disinfection processes. Of the six tubes collected, five presented cloudiness of the BHI culture medium. After disinfection and cultivation in new BHI, the tubes disinfected with 2% chlorhexidine by friction and immersion, as well as with 1% sodium hypochlorite by immersion, demonstrated good performance. When seeded in Petri dishes, only the use of 2% chlorhexidine by friction showed no growth. Although the method with 2% chlorhexidine by friction appears more effective, further studies are needed to determine the best disinfection method.

Santos et al.,18 emphasized that the use of intracanal medicament as an aid in postoperative control is relevant during endodontic treatment in cases of persistent or secondary infections, since chemical-mechanical preparation is insufficient in these cases due the complexity of root canal system. It thus acts as a complementary step for disease regression, reaching areas inaccessible to instrumentation and reducing the bacterial load. There are several variations in its clinical indications, and failure to select this medication compromises the treatment. This study aims to review the literature on the use of intracanal medicament in endodontic therapy. Methodology: Scientific articles indexed in the PubMed, Scientific Electronic Library, and Google Scholar databases were collected. Results and Discussion: The selection of an MIC should consider three main aspects: antimicrobial potential; histocompatibility; and the ability to stimulate host tissues to promote tissue repair. The medication can contribute decisively to the maximum elimination of endodontic microbiota, being directly related to better periradicular tissue repair and, consequently, to a higher success rate in endodontic therapy for teeth with infected canals. The effectiveness of MIC is only considered after endodontic treatment is completed after follow-up for a period of 6 months. They concluded that endodontic treatment depends on complementary factors for its success, in addition to mechanical instrumentation and irrigating solutions, where the use of MIC contributes to the process of repairing periapical lesions, making patient follow-up essential.

Soares et al.,19 emphasized that intracanal medicaments are a fundamental part of endodontics, used to disinfect and promote healing of root canals. This process involves the application of chemicals within the root canal to eliminate pathogenic microorganisms, reduce inflammation, and promote tissue repair. Among the various medications used, calcium hydroxide stands out for its antimicrobial properties and ability to induce the formation of mineralized barriers. This study aimed to highlight, through a literature review, the main intracanal medicaments and their properties and applications in endodontics. This bibliographic research included 39 scientific articles found in the PubMed, SciELO, and Google Scholar databases. The literature review was conducted using an exploratory method and a qualitative approach, analyzing relevant studies that address the biological and chemical aspects of these medications. The main results indicate that calcium hydroxide, when combined with different vehicles, exhibits significant variations in its antimicrobial efficacy and biocompatibility. Inert vehicles, such as distilled water and glycerin, do not significantly alter the properties of calcium hydroxide, while biologically active vehicles, such as PMCC and chlorhexidine, provide additional antimicrobial effects. Water-soluble vehicles provide rapid antimicrobial action, while oily vehicles ensure prolonged action. They concluded that calcium hydroxide remains one of the most widely used agents in endodontics due to its good antimicrobial capacity and biocompatibility. The choice of vehicle is crucial for the effectiveness of intracanal medicament. The combination of calcium hydroxide with PMCC broadens the spectrum of antimicrobial action.

The PRP® Endodontic Solution, packaged in 5 1ml tubes, is a solution (FORMULA AND ACTION. PRP® Endodontic Solution 2025)20 indicated as intratracanal dressing of dead pulp and retreatment, aiding in the disinfection of canals after odontometry and initial emptying. With a formula based on parachlorophenol and antimicrobial in a water-soluble vehicle, the solution is ideal for when canal preparation is not complete. Therefore, this solution should be used after disinfectant penetration or partial instrumentation of the root canal when the presence of microorganisms is suspected. It consists of an antimicrobial solubilized in a viscous, water-soluble vehicle. Its composition includes parachlorophenol, polyethylene glycol 400, benzalkonium chloride, sodium chloride, and deionized water.

Ultimately, such events represent a significant risk to clinical biosafety with direct implications for professionals in the field and individuals undergoing treatment, as such contamination compromises the reliability of endodontic treatment and, in more severe cases, causes problems for patients. In view this study aimed to evaluate presence microorganisms on surface and inside PRP® intracanal medication tubes during the application of intracanal medication, also investigate possible biosafety failures and risks cross-contamination.

This study consists of experimental investigation conducted in the microbiology laboratory of University of São Francisco (USF). The purpose this study was to evaluate occurrence microbial contamination of PRP® intracanal medication tubes, analyzing not only the internal contents but also the external surface of these tubes.

It should be noted that, because this is a laboratory investigation without the involvement of humans or animals, submission to the Research Ethics Committee was not required, as provided for in CNS Resolution No. 510/2016.

PRP® medication tubes, carpule syringes, sterilized needles, an incubation oven (370°C/48h), disposable calibrated loops, and blood agar plates were used.

Initially, 5 drops of tube contents were added Nutrient Agar plates using a sterile carpule syringe, inside a laminar flow cabinet, after sanitizing the tube surface with 70% alcohol. The contents were streaked using a sterile loop. Two plates were prepared each tube, one incubated aerobically at 370°C 48 hours and other incubated anaerobically at 370°C 72 hours, with an unused tube serving as negative control.

To assess external surface contamination, a pre- and post-clinical use comparison protocol was adopted. After initial decontamination by rubbing with 70% alcohol, the first smear was made on nutrient agar (baseline condition "Pre") with aseptic gloves. The tubes were then subjected to clinical use in endodontic procedures by three students, being reevaluated with a new post-procedure smear ("Post") condition. Samples from both stages were incubated together aerobically (370°C for 48 hours). The tubes were selected by students under the supervision of the lead researcher, ensuring adherence to the following previously established criteria: all samples were within their expiration date, had intact packaging, contained similar amounts of product, and had been used at least once, with most having been used two to three times previously.

Samples that did not meet these criteria, such as those with damaged packaging, expired product, or discrepant content volumes, were excluded from the analysis to ensure standardization of the tests.

The results were read by visual inspection after the incubation period.

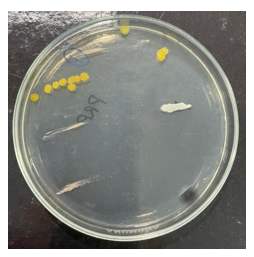

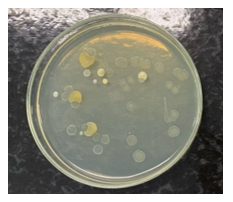

Eighteen PRP® tubes clinically used in endodontic treatments were evaluated, selected according to pre-established criteria of expiration date, packaging integrity, and adequate volume. Microbiological evaluation of the internal contents revealed contamination in 22.2% of the samples subjected to aerobic incubation (4 of 18) (Figures 1 and 2) and 5.9% under anaerobic conditions (1 of 17) (Figures 3 and 4), while the control group of unused tubes remained sterile, validating the methodology.

Figure 1 Growth of three different microbial species under aerobic conditions.

Source: The authors, 2025.

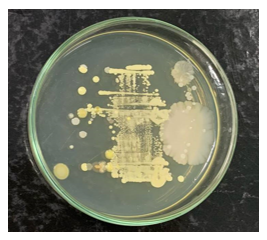

The external surface of the tubes was evaluated using a direct smear technique on nutrient agar. A significant increase in bioburden was observed after clinical handling by 3 operators, compared to baseline pre-use conditions. This increase demonstrates cross-contamination mediated by contact with contaminated gloves, transfer from instruments, or deposition of aerosols from the surgical field (Figures 5 and 6). Regarding the microbial profile of the internal contents, three distinct species were identified under aerobic conditions, compared to only one species under anaerobic conditions, notably one sample with simultaneous growth under both conditions (polymicrobial contamination). This asymmetry suggests greater vulnerability to colonization by environmental microorganisms under oxygenated conditions.

Figure 5 External surface of the tube before clinical use, with low microbial load.

Source: The authors, 2025.

Figure 6 External surface of the tube after clinical use, with increased bioburden.

Source: The authors, 2025.

A significant operator-dependent pattern was evidenced: 80% of contamination occurred in tubes handled by three specific operators, while samples handled by five other professionals remained sterile. This variability indicates divergences in biosafety practices during clinical handling, with no correlation with the number of previous uses (2-3 times).

Considering all analyses performed (35 tests), the overall contamination rate reached 14.3%, reinforcing the need for strict protocols for handling these intracanal medicaments.

Intracanal medicament plays a decisive role in endodontics, offering biological and chemical properties essential for the success of endodontic treatment. Paramonochlorophenol, despite its high cytotoxicity, remains an important agent due to its potent antimicrobial activity. Endodontic intervention consists of treating the clinical consequences resulting from the inflammatory response or necrosis of the dental pulp. The primary objective of this therapeutic approach is to prevent the onset of infectious processes in cases where the pulp is still vital, as well as to control and eliminate already established infections in cases of pulp necrosis. This goal seeks the complete elimination of aggressive agents present in the root canal system, including microorganisms, their metabolic byproducts, and organic debris originating from the pulp tissue, regardless of its condition. Furthermore, another reason for greater disinfection the root canal system is use of intracanal medication, as Ricucci and Siqueira4 confirm, in teeth with mortified pulp, intraradicular bacterial biofilms, including extraradicular biofilms, are prevalent. But that's not all. These microorganisms are found throughout the dentin walls of the main canal, as well as in lateral canals, apical branches, and isthmuses, including deep within the dentinal tubules.

Although the contamination of anesthetic tubes is widely documented, there is a lack of studies specifically evaluating the microbiological safety of PRP® tubes reused in clinical practice. This gap is concerning, since the combination of water-soluble vehicles (PEG 400 and Rinossoro) with PMC can create a distinct environment for microbial proliferation, requiring dedicated analysis. In this context, it is essential that the dentist be fully trained to recognize and correctly execute all stages of the endodontic protocol. Mastering the internal anatomy of the root canal system is a fundamental starting point, as it allows for an understanding of its three-dimensional complexity. This anatomical understanding significantly contributes to proper modeling and, consequently, to effective obturation, capable of promoting a hermetic seal of the root canal.

Chemical-mechanical preparation represents an essential step for the success of endodontic therapy. This phase is characterized by the combined action of mechanical instruments and irrigating solutions, and is responsible for decontaminating the canal system in cases of dead pulp, as well as maintaining the aseptic chain in pulpectomy procedures. Although chemical-surgical preparation is valuable, it alone is insufficient to ensure complete disinfection of the root canals, especially given the anatomical complexity encountered. Difficulties related to visualization and instrumentation of all branches of the canal system limit the effectiveness of mechanical intervention alone.

Given these limitations, the use of intracanal medication becomes an essential therapeutic strategy. This step's main function is to eliminate residual microorganisms that were not removed during the initial preparation. Furthermore, it acts as a physical-chemical barrier against recontamination of the canal system between clinical sessions, also contributing to the control of the local inflammatory process. The antimicrobial efficacy of the substances used, combined with their ability to modulate tissue response, reinforces the importance of this phase in endodontic treatment.

The PRP® intracanal medication tube is prepared in compounding pharmacies and contains 1.8 mL, allowing for multiple uses. However, when stored or handled improperly, it can become a vector for cross-contamination and, furthermore, promote the transport of microorganisms into the medication. Pulp necrosis is characterized by the presence of intracanal microorganisms. In more advanced stages, it can extend to the periapex, resulting from pulp death. This occurs when the pulp's metabolic activity and response to aggressive agents have ceased and become ineffective. Consequently, the periapex becomes responsible for immunological protection, forming a periapical lesion through bone resorption and dental cementum.

Considering this information, we note that chemical-surgical preparation, although the most crucial component for effective decontamination of the root canal system, is not completely sufficient, as it does not extend to all sites that bacteria can reach, such as secondary canals and the periodontium. For effective, physiologically compatible disinfection, intracanal medications are used, which have been shown to be successful in reducing residual microorganisms after canal preparation, as well as reducing the microbial load in accessory canals.7

Furthermore, another important issue that highlights the importance of using intracanal medication during endodontic treatment is that, in addition to bacteria from the contaminated canal, secondary contamination may also occur from the surgical procedure itself, in the case of inadequate absolute isolation, insufficient instrumentation, and insufficient disinfection.18

Therefore, PRP® is the intracanal medication of choice in cases of pulp necrosis, unless, for adverse reasons, the preparation cannot be completed. This preparation consists of: Rhinossoro, an aqueous water-soluble vehicle; Polyethylene glycol, a viscous water-soluble vehicle; and the base is Paramonochlorophenol, an antimicrobial agent.2,8

Paramonochlorophenol (PMC), widely used due to its potent antiseptic action, exerts antimicrobial and antifungal activity due to the slow release of chloride ions in the para position of the phenolic ring, combined with the action of phenol, which disrupts the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane, denatures proteins, and inactivates enzymes. It occurs in the form of crystals with a characteristic phenolic odor. To reduce its cytotoxicity and improve biocompatibility, PMC is often diluted or combined with other substances, such as camphor, to form camphorated paramonochlorophenol (PMCC), as well as other combinations such as furacin or water.

Among the advantages of PMC is its strong antimicrobial efficacy against a variety of microorganisms, essential for the success of endodontic treatment. However, PMC is not without its disadvantages. The main one is its high toxicity, especially if not used properly. It is recommended that its application be limited to the short term, for up to one week, as PMC can be irritating to tissues when used for a long period, in addition to being associated with the risk of inducing bacterial resistance when used indiscriminately.12,19

According to Fórmula & Ação®, Rinossoro is composed of Benzalkonium Chloride, Sodium Chloride, and Deionized Water, with the function of improving tissue compatibility, minimizing irritant effects as it is an isotonic vehicle.20

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is used as a vehicle in the formulation of camphorated paramonochlorophenol (PRP®). The selection of this vehicle is crucial, as the type of vehicle used decisively influences the therapeutic efficacy of the intracanal medication. It is a chemically inert substance that does not interfere with the antimicrobial activity of paramonochlorophenol, exhibiting neither synergistic nor antagonistic effects. Furthermore, due to its viscous nature, PEG promotes a gradual release of the active ingredient, contributing to the prolonged maintenance of the therapeutic effect, although the intensity of the initial action may be lower compared to aqueous vehicles.19

Contrary to these findings, Nassri et al.,3 indicate that PRP® showed larger inhibition zones, indicating greater antimicrobial potential, although bacterial growth occurred in all tubes in a liquid medium. On the other hand, the application of intracanal medicament (ICM) differs in that it does not involve reflux. It is also noted that its composition contains paramonochlorophenol (PMC), an antimicrobial agent. Although its function is to combat bacteria that cause endodontic infection within the canal, this medication is also expected to help reduce the risk of contamination inside the cartridge. However, PMC can be aggressive if it comes into contact with periapical tissues.5,12

To insert the medication into the root canal, a short 30G needle attached to a carpule syringe should be used. The application should be performed with the canal previously dried, filling it completely. If the medication leaks into the pulp chamber, the excess should be aspirated. Next, a sterile cotton dressing is placed in the pulp chamber and a temporary restoration is placed, ensuring the canal is sealed and preventing external contamination.2,7

Therefore, measures must still be taken to ensure effective biosafety, such as not reusing the needle applied during local anesthesia and disinfecting the external area using strict aseptic techniques. It is also important to ensure that the tube has not been contaminated with any biological fluid during the surgery.

Cross-contamination is the transmission of pathogens, which can occur between patients or between patients and professionals. It is a relevant factor that requires the attention of dental professionals in daily clinical practice, who must strictly follow safety protocols. Since it occurs through contact with secretions such as blood and saliva or aerosols, it can trigger the transmission of various diseases.6,17

Although not considered a semi-critical article, given that there is contact with skin and mucosa, Mondini et al.,15 raise concerns about cross-contamination in intracanal medication tubes. There may be a risk of contact between the outside of the tube and fluids, and if the needle used for insertion is contaminated, this could lead to complete contamination of the tube, according to Mendes Vilarino.9 Also during handling, there is contact with the dentist's gloves, violating microbiological integrity, according to Queiróz and Carvalho.17

Another concern, according to Haddad Filho et al.,6 is the importance of dentists and undergraduate students regarding the possibility of contamination during tube storage. A study carried out in which samples were collected from the inside of suitcases belonging to undergraduate students at four different universities found the presence of microorganisms in all of the suitcases, reinforcing the importance of proper hygiene, both of the suitcases and the asepsis of the tubes.

On the other hand, a previous investigation conducted by Silva Júnior et al.,1 concluded that 25 of the 38 samples analyzed in anesthetic tubes not subjected to clinical use contained the presence of gram-negative bacilli, gram-positive cocci of the genus Staphylococcus, and fungi. The authors attributed the microbiological contamination largely to inadequate packaging and transportation conditions, which can compromise the sealing barrier provided by the tubes' rubber and metal caps. Furthermore, they emphasized that the transfixion of these caps by the needle can act as an access route for the introduction of microorganisms into the tube, which poses a potential risk of infection during administration of the anesthetic agent. In fact, ideally, the entire intracanal medication tube should be used during the treatment session and discarded afterward, taking care to use a sterile syringe and a new needle during the intracanal medication procedure. This avoids cross-contamination when using PRP®, which occurs in daily clinical practice. However, it is essential to change needles and syringes occasionally, as this is the only way to avoid such unforeseen events.

It should never be forgotten that the oral cavity harbors a complex microbiota, composed of various microorganisms that, under certain circumstances, can act as agents in the spread of systemic diseases, as Queiróz and Carvalho17 point out for clinical material. In cases of bacteremia, characterized by the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream, these microorganisms can reach vital organs such as the heart, lungs, brain, and joints, and have also been associated with the induction of premature births.

This reality highlights the importance of academic training in consolidating safe practices, as demonstrated by Jesus and Câmara.13 The authors postulate that the internalization of biosafety principles occurs more effectively when they are adequately taught and practiced during undergraduate studies, becoming an integral part of professional practice. This finding reinforces the need for more effective pedagogical approaches in dental curricula, with an emphasis on the correlation between theory and practice.

Thus, primary sanitation of surfaces and containers that hold dental materials, such as clinical benches and instrument cases, is a fundamental measure in controlling the spread of microorganisms, as demonstrated by Haddad Filho6 in cases carrying materials and instruments. In fact, Silveira et al.,14 report that AgNP solutions are a potential alternative for surface disinfection, highlighting the effectiveness of disinfection with silver nanoparticles as a complementary method in this process. Haddad Filho et al.,16 reported that this study specifically evaluated surface contamination on intracanal medication tubes through comparative microbiological analysis before and after use, using culture medium as a substrate. The results revealed the presence of residual microbial contamination even before the tubes were used, with significant worsening after clinical handling.

It is important to highlight that the analysis identified that the main source of contamination came from the operational procedure, not the patient's oral cavity, reinforcing the need for rigorous biosafety protocols. These findings suggest crucial flaws in fundamental steps such as inadequate hand hygiene, incorrect use of protective barriers, and improper handling of supplies. Such operational deficiencies can lead to the iatrogenic introduction of microorganisms during clinical procedures, in addition to enabling cross-contamination of other instruments when materials are not adequately disinfected after use.

This is not to mention the contamination previously described by Silva Júnior et al.,1 who identified the transport of microorganisms through the process of attaching needles to virgin anesthetic tubes, specifically through their rubber and metal caps. This mechanism can occur in PRP® tubes after clinical use, considering the needle's perforation of the plunger, which can transport microorganisms from the external surface and the possible retrograde aspiration of contaminated fluids. Furthermore, the antimicrobial action of paramonochlorophenol (PMC) has limited efficacy against pathogens and their metabolites, posing a significant risk of cross-contamination when these materials are used on different patients, or even on the same patient.

Given these results, it is recommended that individualized dosing systems be adopted to avoid sharing tubes between patients, thus eliminating the risk of cross-contamination. At the same time, it is essential to implement rigorous disinfection protocols, including the use of effective antimicrobial agents, such as silver nanoparticles, for surfaces and materials, along with ongoing training of professionals and students in aseptic techniques and infection control. It is also recommended that further studies be conducted with larger and more diverse samples, covering different clinical and institutional contexts, to validate the generalizability of the findings and improve biosafety guidelines in the field. Regarding the diversification of chemical disinfectant agents, Medinger10 investigated the effectiveness of agents in disinfecting anesthetic tubes using 70% alcohol, 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution, 2% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution, 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution, 2.5% sodium hypochlorite, and 10% povidone-iodine by friction one minute keeping them on sterile gauze until the chosen agent dried. Using a plastic a glass tube each agent, microbiological collection and incubation were then performed, followed by colony-forming unit counting. Most effective chemical friction agents were PVPI (povidone-iodine), 2.5% sodium hypochlorite, and 0.12% chlorhexidine. Concluded that prior disinfection of the anesthetic tube was necessary. In addition, Dutra et al.,11 confirmed that anesthetic tubes need to be disinfected before use, as are not sterile. Of three disinfectant solutions used to reduce microbial load anesthetic tubes, subjected different methods and disinfectant agents (70% alcohol, 7% chlorine dioxide; 5.2% benzalkonium chloride with 3.5% polyhexamethylene biguanide) immersion or friction methods, the tubes were seeded in culture medium. Study concluded that 70% alcohol and 5.2% benzalkonium chloride with 3.5% polyhexamethylene biguanide were more effective eliminating the microbial load tubes by friction method compared to immersion.

Given the above, it is urgent to evaluate clinical practices related to biosafety, including storage, transportation, tube reuse, and material disinfection processes. These protocols ensure maximum microorganism elimination, whether by immersion or friction, and ensure that the agent is proven effective, such as silver nanoparticles, with high antimicrobial potential, low cost, and easy to obtain. Furthermore, a review of current clinical practices is urgently needed, especially in academic and professional settings where the reuse of materials is common.

These gaps, identified primarily among students, highlight the importance of more rigorous academic training in biosafety, with an emphasis on the internalization of protocols from undergraduate level, ensuring that future professionals adopt safe practices as an integral part of their clinical routine. Furthermore, reusing tubes, even with the presence of antimicrobial agents such as paramonochlorophenol, proved insufficient to guarantee product sterility, especially given microbial resistance and the complexity of the oral microbiota, which can compromise the drug's therapeutic action.

Although the study has limitations, such as the small sample size and the controlled laboratory setting, its results highlight tangible risks to clinical safety. Cross-contamination in endodontic materials not only compromises therapeutic efficacy but also exposes patients and professionals to potential systemic complications, such as bacteremia and secondary infections, which can significantly impact individuals' overall health. There is evidence that the shared use of PRP® tubes in endodontic treatment poses a significant biosafety risk. Therefore, the presence of multiple microbial species, identified under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Figures 1–6), suggests significant failures in aseptic protocols during the handling and storage of the drug, confirmed by previous studies that warn of cross-contamination in reused dental materials. The observed contamination is directly associated with operational deficiencies, such as inadequate hand hygiene, improper handling of supplies, and lack of standardized storage.

Finally, let it be clear that reusing PRP® tubes in multiple patients is an unsustainable practice from a biosafety perspective. The transition to individual systems and the adoption of robust preventive measures are imperative to align endodontic practice with contemporary ethical and scientific principles. Such changes will not only preserve the integrity of the treatment but also ensure the comprehensive safety of patients and professionals, consolidating dentistry as a specialty committed to excellence and the prevention of avoidable risks.

Based on the results obtained, it seems valid to conclude that microbiological analysis of the samples revealed microbial contamination both on the external surface and in the internal contents of the tubes.

Nothing.

All data examined during this study are accessible from the author upon acceptable request.

All data analyzed during this research are available from the corresponding author upon wise request. The authors reveal no conflicts of interest regarding neither of the products or coorporation debated in this article.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Filho, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.