Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 16 Issue 4

1Student, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

2 Specialist in Orthodontics, Orthodontics and Periodontics Unit, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

3Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry and Dentomaxillofacial Orthopaedics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

4 Instructor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry and Dentomaxillofacial Orthopaedics, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

5Assistant Professor, Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de los Andes, Chile

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Conservative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

7Specialist in Periodontics, Orthodontics and Periodontics Unit, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, Chile

Correspondence: María Angélica Michea, Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile, Chile

Received: September 15, 2025 | Published: October 3, 2025

Citation: Landeros IG, Contreras CN, Zura M, et al. Finite element analysis in orthodontic biomechanics for patients with reduced periodontium: a scoping review. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2025;16(3):139-145. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2025.16.00657

Introduction: Orthodontic treatment in patients with a reduced periodontium (RP) poses a clinical challenge due to alterations in periodontal support-bone loss, dental migration, and a displacement of the center of resistance. These conditions increase the risk of tissue damage when conventional orthodontic forces are used. Finite element analysis (FEA) has emerged as a useful tool for studying stress distribution in supporting tissues and optimizing biomechanical planning in such cases.

Objective: To review the available scientific evidence on the application of FEA in orthodontic biomechanics for patients with a reduced periodontium, assessing its clinical utility for therapeutic decision‑making.

Methodology: A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus using terms related to “finite element analysis,” “orthodontics,” and “reduced periodontium.” Original studies using FEA in three‑dimensional (3D) orthodontic models with simulated reduced periodontium, published between 2020 and 2025, were included. Animal studies, in vitro studies without clinical correlation, and duplicates were excluded.

Results: Eleven studies were included, with models constructed using cone‑beam computed tomography (CBCT) or 3D scans. In all cases, FEA allowed the identification of critical stress areas, especially in the cervical region of the periodontal ligament (PDL). Forces exceeding 60g and movements such as rotation, tipping and bodily translation were associated with an increased risk of surpassing the physiological hydrostatic threshold, favoring resorption. Biomechanical approaches such as cantilevers, segmented arches and aligners with controlled displacements showed more favorable outcomes. Limitations: considerable methodological heterogeneity in models and the magnitudes of the forces, together with limited direct clinical validation, prevented quantitative synthesis.

Conclusion: FEA is an effective tool for evaluating and predicting tissue responses to orthodontic forces in a reduced periodontium. Its clinical application enables personalized treatment planning, minimizes iatrogenic risks, and promotes an evidence‑based interdisciplinary approach. However, FEA should complement, not replace, clinical evaluation and judgment.

Keywords: Finite element analysis, periodontal attachment loss, orthodontics, biomechanics

Periodontitis and its progression are associated with multiple alterations and sequelae in the stomatognathic system, with loss of periodontal attachment being the major sequela that defines a reduced periodontium (RP). This results in rotations, extrusions, diastemata, and secondary occlusal trauma. These alterations, related to the loss of periodontal supporting tissues, require interdisciplinary orthodontic–periodontal treatment for appropriate correction and functional rehabilitation.1 Notably, orthodontic treatment may be associated with a decreased prevalence of periodontitis.2

However, orthodontic treatment in patients with RP is complex because pre‑existing bone loss significantly alters dental biomechanics and the behavior of periodontal tissues when forces are applied.3 Since the tooth’s centre of rotation is displaced apically in RP, orthodontic mechanics must be personalized and aimed at reducing stress and preventing overload in compromised structures.4 Considering these factors, orthodontic treatment in RP provides functional and aesthetic benefits, enhancing occlusal stability and long‑term periodontal health.5

Given the smaller amount of periodontal ligament (PDL) available to dissipate orthodontic forces, these cases require personalized treatment plans and specific biomechanical considerations. The therapeutic goal is to prevent further bone resorption and avoid damaging the remaining periodontal tissues, which involves working with patients who have a stabilized periodontium, no periodontal infection, and reduced, controlled forces so that tooth movements do not cause tissue damage. Therefore, the magnitude of the applied force and biomechanical control are essential to avoid harming periodontal tissues. In terms of orthodontic biomechanics, segmented arches break the appliance into independent units, allowing for localized and controlled forces. Following this approach, cantilevers are commonly used to produce controlled, case-specific tooth movements, compensating for the apical displacement of the centre of resistance present in teeth with RP.6

In this context, finite element analysis (FEA) is valuable because it is an advanced computational simulation method used to predict how biological tissues behave under various biomechanical conditions, including loads, forces, and mechanical stress.7 The tool is based on simplifying a complex system by dividing it into smaller, manageable units called “elements.” Each element is assigned mechanical properties that describe its behavior when subjected to an external force, such as mastication or orthodontic forces. All these elements are interconnected by “nodes,” creating a three‑dimensional mesh.8,9 Therefore, specialised software can determine how the object or system responds, allowing detailed visualisation of stress and strain distribution-for example, in the tooth, PDL, and alveolar bone. The ability of FEA to model interactions among the tooth, PDL, and alveolar bone makes it a useful tool for examining orthodontic biomechanics within a reduced periodontium.9,10

Despite the growing number of FEA studies in orthodontics, the literature remains heterogeneous in terms of modelling assumptions and force magnitudes, limiting comparability across studies.8,11 Moreover, there are no standardised clinical guidelines for applying FEA results to orthodontic decision-making in patients with reduced periodontium, and clinical evidence is still scarce.5,12 Several authors also highlight the need for direct clinical validation of FEA findings before they can be translated into routine practice.9,13 These gaps justify the need for a scoping review to synthesize the current evidence and outline future research priorities.

The objective of this review is to answer the PCC‑format (Population, Concept, and Context) research question (Table 1): How has finite element analysis been used to inform orthodontic biomechanical planning in periodontally reduced dentitions, including recommended movements, force magnitudes, and high-risk stress areas?

|

Component |

Definition |

|

Population |

Human teeth/segments with reduced periodontium (clinical or simulated from CBCT/3D scans; human ex-vivo). Animals excluded. |

|

Concept |

Finite element analysis (FEA) applied to orthodontic biomechanics (stress/strain, displacement/torque, M/F, PDL/bone/ANB), including fixed appliances, segmented mechanics, cantilevers, aligners, TADs. |

|

Context |

Orthodontic-periodontal planning/decision-making. |

Table 1 PCC framework

Search protocol and development of the review

This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines.14,15 A structured search was carried out in PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus using the following terms: “Finite element analysis,” “Orthodontics,” “Orthodontic treatment,” “Periodontium,” “Periodontal support,” “Periodontitis,” and “Reduced periodontium,” combined with Boolean operators (AND/OR). The search was performed between April and July 2025. Study selection was conducted independently by two reviewers using the Rayyan platform, with predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria applied at each stage. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and when consensus was not achieved, a third reviewer was consulted.

Table 2 summarizes the eligibility criteria applied. Full-text articles were included if they specifically employed FEA to analyze orthodontic biomechanics in patients with a reduced periodontium, whether due to periodontitis or other conditions leading to loss of bone support. In addition, in vitro studies were accepted only when based on clinically relevant human data-such as CBCT, 3D digital scans, or ex-vivo maxillary bone/dental samples-since these provide anatomically valid simulations of reduced periodontium conditions. By contrast, purely theoretical computational models relying on oversimplified geometries (e.g., cylinders or blocks to represent teeth, bone, or the periodontal ligament) or arbitrary assumptions without anatomical validation were excluded. Animal studies, reviews, abstracts without full text, duplicates, and incomplete reports were also excluded. Eligible studies were limited to publications in English between 2020 and 2025 that directly addressed the aim of the review.

|

Criterion |

Included if |

Excluded if |

|

Studies with three‑dimensional (3D) models applying FEA |

FEA applied to 3D models simulating teeth and supporting structures |

Used 2D models or simplifications without real anatomical basis |

|

Studies simulating reduced periodontium or marginal bone loss |

Model includes vertical bone loss or explicit description of RP |

Healthy periodontium or no simulation of bone loss |

|

Application of active orthodontic forces (specific movements) |

Movement analyzed (e.g., intrusion, retraction, tipping, bodily translation) |

No orthodontic force applied or exclusively static analysis |

|

Original studies (in vitro / clinically relevant simulation) |

Original studies published in indexed scientific journals |

Reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, abstracts without full text |

|

Full‑text accessibility |

Available for full reading |

Only abstract available |

|

Human studies or human anatomical models (CBCT, scans) |

Models based on human tomography or scanning |

Animal models, laboratory‑only or invalidated 3D models |

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in the review

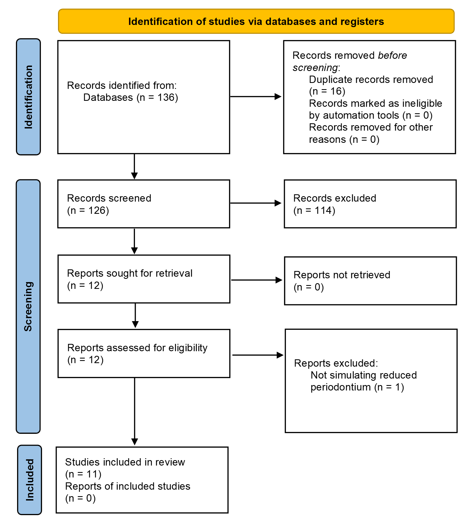

Following PRISMA 2020 (Figure 1), a total of 136 articles were identified through the systematic search in PubMed (n=105), Web of Science (n=25) and Scopus (n=6). Sixteen duplicates were removed, leaving 126 unique records for screening.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of literature search and selection criteria, based on the PRISMA 2020 statement.

Study selection was performed independently by two reviewers, using pre‑defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), in two stages: (1) screening of titles and abstracts, and (2) full‑text evaluation. At the title‑screening stage, 12 studies were initially selected as clinical studies conducting FEA and directly related to orthodontic treatment and periodontal condition in patients with reduced periodontium or a history of periodontitis. During full‑text review, one study was excluded for not satisfying the criteria. Finally, 11 studies that fully met the PCC criteria were included for analysis in the review (n=11).

All selected articles (Table 3) relate to FEA studies conducted on computational orthodontic models with RP due to periodontitis stages III–IV or on computationally simulated reduced periodontium. The three-dimensional models were obtained via CBCT from adult patients aged 19–29 years, or through 3D scanning of maxillary bone autopsies or study dental models with RP. These models were then digitized in software to generate 3D images of alveolar bone and dental structures, which were subsequently analyzed using FEA.

|

No. |

Author (year) |

Model/sample type |

Orthodontic movement evaluated |

Reduced periodontium (degree) |

Force applied in RP (g) |

Key findings |

Clinical recommendation |

Study limitations |

|

1 |

Frias et al.6 |

FEA based on clinical images (CBCT). Maxilla with protruded incisors. |

Intrusion, extrusion and en‑masse movement with cantilever. |

Moderate–severe RP, clinical by CBCT images |

60 g |

Greater stress concentration in RP; higher PDL strain. Forces >100 g cause excessive stresses. |

Apply light forces and assess direction; avoid direct intrusive movements. |

Maximum/idealized anchorage was assumed. Condition not clinically reproducible. |

|

2 |

Gameiro et al.8 |

FEA individualised by bone level. Anterior maxillary zone. |

Intrusion, retraction with segmented arch and cantilever. |

Variable bone reduction, simulated by modifying the FEA model |

20–50 g |

Stress zones increased in RP; force‑application points must be adapted due to apical displacement of the center of resistance. |

Low, localized forces according to level of bone support. |

A single human specimen; model oriented toward initial movement rather than the entire treatment; results are not directly generalizable to the clinical population. |

|

3 |

Luchian et al.9 |

Mandibular anterior FEA |

Protrusion, retraction |

Simulated 3D bone reduction in mandibular incisors |

50–100g |

Forces <100 g are safe; risks with >100 g in severe RP. |

Use <100 g in RP; avoid prolonged displacements. |

The authors indicate the need for future studies to further investigate and validate findings. |

|

4 |

Ma et al.10 |

FEA with aligners at different RP levels |

Tipping with aligners |

Mild, moderate and severe, modelled in virtual aligners |

25–100g |

Aligners generate greater tipping in severe RP. Displacements >0.15 mm with moderate bone loss generate risk of deformation at the alveolar crest. |

Control root torque; consider reinforcements in aligners. |

Single case in vitro; model properties do not fully replicate clinical settings; clinical validation required. |

|

5 |

Moga et al.13 Part I |

FEA of 81 premolars (CBCT of 9 patients) |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

0–8 mm bone loss simulated from 9 patients’ CBCTs |

50g |

50 g is safe; PDL responds with higher stress under tipping and rotation. |

Use <40 g after ≥4 mm bone loss. |

The authors acknowledge the limitations of the assumptions of isotropy, linear elasticity, and homogeneity, which do not reflect the actual behavior of tissues. |

|

6 |

Moga et al.16 Part II |

Same cohort as Part I (FEA of 9 patients) |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

Same cohort; bone loss up to 8 mm in 81 models |

50g |

The apical neurovascular bundle (ANB) shows higher sensitivity to intrusive forces in RP. Intrusive forces ≥60 g are harmful to the ANB in RP. |

Avoid direct intrusion in teeth with bone loss. Rotation and tipping are most harmful to the ANB in RP. |

The authors acknowledge the limitations of the assumptions of isotropy, linear elasticity, and homogeneity, which do not reflect the actual behavior of the ANB. |

|

7 |

Moga et al.18 |

Comparative FEA of cortical vs trabecular bone |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

FEM comparison between cortical vs trabecular loss in RP |

50–200g |

Trabecular stress is more sensitive to force increments. |

Avoid abrupt increases; allow progressive adaptation. |

The authors indicate that the model is based on assumptions of isotropy, homogeneity, and linear elasticity for cortical and trabecular bone, and that the results require further clinical validation. |

|

8 |

Moga et al.22 |

FEA with progressively increasing force |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

Progressive simulation of bone loss 0–8 mm with different forces |

60–240g |

Bone resorption increases with >120 g in RP. |

Limit forces to <60 g if bone loss ≥4 mm. |

The authors acknowledge inherent limitations of the FEA method and the need for clinical correlation. |

|

9 |

Moga et al.17 |

FEA on tissue absorption and dissipation in teeth and periodontium |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

Gradual RP of 1–8 mm; absorption of forces in hard and soft tissues |

60–240g |

Enamel and dentine act as similar absorbing structures. |

Use <60 g to avoid ischaemia in soft tissues. |

Not explicitly reported by the authors. |

|

10 |

Moga et al.23 |

FEA with bracket in gradual horizontal RP |

Intrusion, extrusion, tipping, rotation, translation |

Horizontal RP of 0–8 mm with metal brackets present |

50g |

Stress distribution in the bracket is not altered by RP. |

No need to modify bracket design, but control force magnitude. |

The authors highlight that previous studies have limitations (theoretical/in vitro and difficulty in applying pure shear loads). This motivated the clinical approach of the study. |

|

11 |

Sioustis et al.20 |

3D FEA from a single patient’s CBCT |

Protrusion |

Reduced but healthy periodontium; no inflammation; single‑patient evaluation |

50g |

Greater root displacement in reduced periodontium. |

Root‑movement control is essential in RP. Use en‑masse movements. |

Not explicitly reported by the authors. |

Table 3 Included articles, review findings and limitations

The biomechanical properties of the anatomical structures in FEA computational models were predefined by the analysis software. These structures were digitally assembled from elements and nodes that accurately replicate the behavior and biomechanics of real anatomical structures, allowing realistic computational simulations of periodontal tissue responses under various biomechanical conditions created by orthodontics. The software enabled investigators to adjust parameters such as bone density, PDL elasticity, and dental material characteristics in the virtual environment. All selected articles examine the application of FEA in orthodontic biomechanics within RP.

Among the selected articles, Frias et al.,6 developed an FEA model of maxillary bone with extruded and proclined incisors in RP. Two stages were analysed: levelling and alignment, and en-masse retraction with cantilever and segmented arches. They found that forces of 100g were excessive, causing extreme PDL stresses and strains. Mechanics with cantilever and segmented arches using lower forces produced uniform intrusion and retraction movements and were safer, indicating that controlled forces along with precise biomechanical planning are vital for patients with periodontal attachment loss. Gameiro et al.,8 developed four computational models with varying levels of alveolar bone resorption, utilizing intrusion and retraction mechanics with three-piece segmented arches. Teeth with reduced periodontal support showed greater displacement and PDL stress; therefore, a 20–25% reduction in applied force in RP is recommended. They also indicated that the location of the point of force application should be adjusted according to the amount of bone loss to maintain controlled movements and minimize risks such as increased bone resorption.

In another study, Luchian et al.,9 conducted FEA of mandibular anterior teeth subjected to orthodontic forces in RP, comparing different anatomical scenarios and varying levels of PDL integrity, with a primary focus on the latter. Their findings indicate that cases with reduced PDL showed higher stress concentrations from the applied orthodontic forces. They also highlight that the cervical areas of teeth are most susceptible to excessive stress. The study supports the use of FEA to personalize orthodontic treatment in RP.

Clear aligners are now increasingly researched. Ma & Li10 used FEA to assess stress and strain distribution in mandibular anterior teeth subjected to controlled displacements with clear aligners, under different axial inclinations (90° and 100°) and varying levels of bone loss (mild, moderate and severe). They concluded that at 100° inclination, 0.18 mm displacements produced stresses similar to 0.20 mm displacements at 90°, reaching 132–164 MPa. In RP, displacement per aligner step should not exceed 0.15 mm when bone loss is present (≥1/3 of root length) to avoid excessive stresses, which mainly affect the cervical region of the alveolar crest.

Moga et al.,16,17 compared the effects of 60, 122 and 244 g on intact PDL and PDL with bone loss (up to 8 mm). They found that forces less than 60g were safe with RP up to 4mm loss; with more than 4 mm, even 60g can surpass the physiological threshold (mean hydrostatic pressure, MHP, 16 kPa). The highest stresses were observed during rotation, bodily translation, and tipping, particularly in the cervical third of the PDL. They recommend reducing forces to 20–40 g when bone loss exceeds 4 mm to prevent ischaemia and resorption. In another study, they evaluated the impact of increasing forces on cortical and trabecular bone using FEA in 81 RP models with bone loss from 0 to 8 mm. Average stress doubled when increasing from 60 g to 122 g and quadrupled at 244 g. Regardless of force magnitude, the locations of highest stress remained consistent, but stress increased with bone loss. Stresses exceeded MHP after 4 mm of loss; therefore, forces should be limited to less than 60 g.18

The biomechanics of orthodontic movements in patients with RP differ from those used in patients with healthy periodontium. For example, the use of cantilevers and segmented arches allows for smaller forces, resulting in more controlled and physiologic movements. In the study by Frias et al.,6 FEA showed that lower forces applied with a segmented arch produced uniform intrusion and retraction. Similar findings were reported in clinical studies by Re et al.,12 for intrusion using segmented mechanics in RP, where intrusion did not affect periodontal health. Another study also recommends segmented mechanics for intrusion and space closure in RP due to better force control and posterior stabilisation.19 Biomechanically, in a dental group connected by a segmented arch, the applied force is distributed across several teeth, and the resulting movement depends on the location of the group's centre of resistance, which is more apical and distal than that of a single tooth-especially with bone loss. This shift in the centre of resistance requires adjusting the moment‑to‑force ratio to achieve controlled movements and prevent harmful tipping or extrusion to protect periodontal tissues.12,19

The dentoalveolar system’s ability to absorb and dissipate orthodontic forces decreases with reduced periodontal support in RP.12 Other studies17,20 have shown that decreased bone volume and PDL integrity lessen the capacity for even stress distribution, increasing the risk of ischaemia, necrosis, and damage to the apical neurovascular bundle (ANB). This aligns with another study where FEA demonstrated that the PDL functions as a key damping system, dispersing stresses from orthodontic loads. When bone height is reduced or PDL continuity is compromised, loads concentrate in specific areas, especially the cervical third, creating stresses that may surpass the physiological threshold and cause adverse periodontal effects. Hard tissues have a lower capacity to dampen forces than the PDL, so overload can lead to bone resorption or structural damage if force levels are not adjusted. These findings support the need to reduce force intensity in RP and to monitor its effects throughout treatment. Overall, the studies included in this review and current literature reinforce the importance of personalised biomechanics that respect the physiological limits of remaining tissues, maximising clinical efficiency and reducing the risk of complications.21

In intact periodontium, orthodontic forces are around 150g; however, in RP they should be reduced to approximately 30g12. This aligns with other authors who compile simulations across multiple clinical scenarios, enhancing understanding of safe biomechanical limits. When bone loss exceeds 4 mm, applied forces should be limited to <40g, especially for rotation, translation, and tipping.17,22,23 Although some studies employed simulated RP models, RP is primarily a condition of adult patients. Therefore, even if simulated models do not always reflect real clinical cases, their results are applicable to adults with RP provided periodontal disease is controlled and biomechanical planning is appropriate (Table 1). Overall, these results highlight the importance of tailoring orthodontic treatment plans in RP, considering not only the magnitude and direction of forces but also specific anatomical features, the type of mechanics used, and the patient’s current and past periodontal health. Interdisciplinary collaboration between orthodontics and periodontics is essential - not optional - at diagnosis, during intervention, and through maintenance. The FEA method offers a detailed and powerful approximation to clinical biomechanics. Despite its potential, limitations include assumptions of homogeneous, isotropic material properties, along with the requirement for user expertise in computational techniques for proper application.11 Nonetheless, the findings of this review reinforce FEA’s value as a predictive and planning tool in RP.24

The present review is subject to important limitations that must be carefully considered when interpreting its findings. First, there was substantial methodological heterogeneity among the included finite element studies. Differences in modelling approaches, assumptions of material properties, magnitude (20 - 240g) and direction of applied forces, types of orthodontic movement (intrusion, tipping, and rotation), degrees of bone loss (mild, moderate, or severe) and selected outcome variables make direct comparison difficult and preclude the possibility of a quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis.8,9,16,18 Second, most studies relied on simplifications inherent to the finite element method, such as isotropy, linear elasticity and homogeneity, which, although necessary for simulation, do not accurately reproduce the anisotropic behavior of periodontal tissues. Third, a potential source of selection bias is that a considerable proportion of the evidence comes from a small number of research groups, often applying similar modelling protocols. This concentration of data may limit methodological diversity and reduce the external validity of the conclusions.

Despite these limitations, some clinically relevant trends can be inferred. Across different models, lighter orthodontic forces -typically in the range of 30–60g- consistently appear safer for patients with reduced periodontium. In contrast, forces exceeding 100 g, were associated with surpassing the physiological hydrostatic pressure and a higher risk of resorptive changes.6,10 Segmental approaches, cantilevers, and controlled aligner mechanics have been shown to reduce stress concentrations and may therefore represent safer biomechanical alternatives in periodontally compromised patients.8 These findings, although preliminary, may serve as a valuable guide for clinicians who must adapt mechanics to minimize iatrogenic risks while still achieving therapeutic goals.

Finally, although some older references such as Re et al.,12 were included, their relevance lies in providing long-term clinical observations that still inform current understanding and contextualize the more recent computational findings. While methodological advances have significantly improved the precision of finite element models in recent years, earlier clinical reports provide irreplaceable evidence of treatment outcomes and long-term stability in patients with compromised periodontal support. Their inclusion serves not to dilute the focus on contemporary evidence, but rather to contextualize and complement the computational findings, bridging the gap between theoretical models and years of accumulated clinical experience.

FEA is an effective tool to simulate and understand periodontal biomechanical behavior under different therapeutic strategies in orthodontics. In patients with RP, its clinic application enables prediction of stress concentration zones, identification of overload risks, and estimation of tissue responses to specific forces, fundamental to prevent iatrogenic effects such as bone resorption, periodontal attachment loss, or root resorption. By modelling complex clinical scenarios, FEA contributes to evidence-based, personalized planning and clinical decisions that balance orthodontic goals with preservation of supporting tissues.

Nevertheless, FEA should be regarded as a complementary resource rather than a replacement for clinical evaluation and interdisciplinary judgment. Its findings need to be validated through controlled clinical studies, particularly randomized clinical trials, that test the magnitudes and directions of orthodontic forces suggested by FEA and assess their long-term impact on periodontal stability, treatment efficiency, and patient-reported outcomes. Future research should also aim to integrate FEA with three-dimensional imaging, patient-specific anatomical modelling, and longitudinal clinical follow-up to bridge the gap between computational simulations and real-world clinical performance.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2025 Landeros, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.