Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

1Department of Histopathology and Cytology, University of Khartoum, Sudan

2Department of Pathology, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Dentistry, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia 4Minstry of Health, Hail, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmed, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, University of Hail 2240, Hai'l, Saudi Arabia

Received: May 09, 2017 | Published: May 16, 2017

Citation: Alobaid AEA, Ebnaof SO, Ahmed HG, et al. Cytological study of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among gathered shish smokers. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2017;7(3):272-276. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2017.07.00240

Background: Oral cancer is one of the 10 top existing cancers and high risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV), represent one of its main causes. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the role of mixed shisha smoking (in groups) in transmission of HPV, as well as, to assess the cellular proliferative activity that might be caused by shisha smoking.

Methodology: Cytological materials were obtained by scraping the surface of the buccal mucosa from 200 apparently healthy volunteers. Out of the 200 individuals, 100 were shisha smokers (cases) and 100 were nontobacco users (controls).

Results: Cytological atypia was identified in 11(11%) of the cases and in only one (1%) of the controls. The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was 12.23(1.55-96.68), P < 0.017. Cytological evidence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection (Koilocytosis) was identified in 9(9%) of the cases in only two (2%) of the controls. The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 4.84(1.02-23.02), P < 0.047.

Conclusion: Mixed shisha smoking is a major risk factor for HPV transmission as well as, for the development of cytological atypia, which might subsequently progress into oral precancerous and cancerous lesions.

Keywords: cytological atypia, HPV, shisha smoking, keratinization, oral cancer

Human papillomaviruses (HPV), particularly, the high risk (HR) types are commonly detected in Sudan and relatively similar to those described in neighboring African countries, though the relative contribution of HR-HPV is substantially lower in cytologically normal women.1 HPV is small DNA virus commonly infecting mucosa and cutaneous keratinocytes. Up to now, at least 200 HPV genotypes are known.2 HPV was assumed to be responsible of more than 99% of the cases of cervical cancer worldwide.3 HPV subtypes have been divided into high- and low-risk on the basis of their oncogenic potential. HR-HPV subtypes are considered to be the leading etiological factors for cervical cancer.2–4 According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 66, regarded as HR-HPV. The HPV types 6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, -53, 54, 61, 72, and 81, regarded as low-risk Human Papillomaviruses (LR-HPV).5 Infections with HPV have been found in a number of body sites, including the skin, larynx, tracheobronchial mucosa, nasal cavity, paranasal sinus, esophagus and oral cavity.6–9 Infection with HR_HPV has been regarded as a potential risk for the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). A number of studies have detected HR-HPV DNA in a considerable proportion of oral cancers with wide variations from 0% to 100% prevalence in oral tissues, perhaps reflecting the characteristic variations in different populations.10–12 Oral cancer is extremely increasing in the Sudan, particularly among men.13 Several studies have linked the etiology of oral cancer to the oral use of Toombak (tobacco specific nitrose amine rich tobacco)14,15 and HPV infection.4–16 In Sudan the prevalence of HPV was reported to be 65%.17 The prevalence of shish (water pipe tobacco smoking) is increasing worldwide and is particularly among adolescents of almost all ethnicities and socio-economic backgrounds.18 In the Sudan, there is a high frequency of shisha usage.19 Most shisha users gather in cafes' and used to use a single water pipe in circular smoking pattern. Such usage may contribute to distribution of infections whether bacterial of viral infections. HPV may distribute through the saliva contamination in the sucking part of the water pipe. Therefore, the aim of the presence study was to screen for HPV among shisha users by cytological evidence (koilocytosis).

In this case controls cross sectional study, a total of 200 Sudanese volunteers living in the city of Khartoum, Sudan were investigated. Of the 200 study subjects, 100 were deemed as current shisha smokers (ascertained as cases) and 100 were non tobacco users (ascertained as controls). All shisha devices were sterile before use. Cytological materials were obtained by scraping the surface of the buccal mucosa. The obtained materials were used for preparation of two direct smears, which were immediately fixed in 95% ethyl alcohol for 15 minutes then sent to the Histopathology laboratory at Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, University of Khartoum, Sudan for subsequent cytological processing.

Sample collection

Oral exfoliative cells were collected from buccal mucosa (covering both cheeks), dorsum of the tongue by a wooden tongue depressor and the obtained materials were directly smeared on clean glass slides and immediately fixed in 95% ethyl alcohol, while they were wet, and finally sent to the cytopathology laboratory for further processing.

Sample processing

Ethyl alcohol fixed smears were hydrated by using descending concentrations of 85% alcohol through 50% alcohol to distilled water for two minutes in each stage. Then smears were treated with Harris’ Hematoxylin for five minutes, to stain the nuclei, rinsed in distilled water and differentiated in 0.5% aqueous hydrochloric acid for a few seconds to remove the excess stain. Then they were immediately blued in tap water for 5 minutes. For cytoplasmic staining they were treated with Eosin for two minutes, then washed in water. The smears were then dehydrated in ascending alcoholic concentrations from 70% through two changes of 95% and absolute ethyl alcohol for two minutes for each change. The smears were then cleared in Xylene and mounted in DPX (Distrene polystyrene Xylene) mounting medium. All reagents used were from Thermo Electron Corporation, UK.

Cytology assessment

The smears were initially assessed for quality reliability by an experienced cytotechnologist. To increase the reliability and reproducibility, firm quality control measures were used. All obtained cytological finding were compared to standard illustrated web images. Smears were examined under low (10X) power using a light microscope. All included smears showed satisfactory staining quality with blue nuclei, orange cytoplasm. To avoid the assessment bias, cytological smears were labeled in such a way that the examiner was blinded to the groups (case group or control group) of each subject. Cytological atypia was assessed cytologically by using the criteria described by Ahmed et al.15

Data analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 16) was used for analysis and to perform Pearson Chi-square test for statistical significance (P value). The 95% confidence level and confidence intervals (95% CI), as well as the Odd Ration (OR) were used. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consent

Each participant was asked to sign a written ethical consent during the questionnaire’s interview, before the obtaining of the specimen. The informed ethical consent form was designed and approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medical Laboratory Research Board.

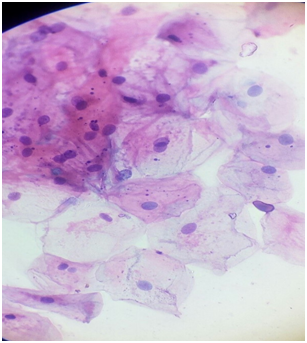

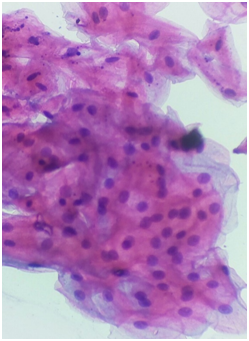

The present study investigated 200 apparently healthy males, their ages ranging from 19 to 56 years old with a mean age of 29 years. The age distribution was relatively similar among the study groups (cases and controls). The majority of the study population was accumulating at age groups23-27 years followed by 28-32 years representing 57 and 47 persons, as indicated in Table 1 & Figure 1. With regard to the education, most participants were with university education followed by basic education constituting 116 and 53 in this order as indicated in Table 1 & Figure 2. Cytological atypia (mild) was identified in 11(11%) of the cases and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 89(89%). On the other hand, cytological atypia was detected in only one (1%) of the controls and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 99(99%)(see microphotographs 1 and 3). The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was 12.23(1.55-96.68), P < 0.017. Cytological evidence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection (Koilocytosis) was identified in 9(9%) of the cases and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 91(91%). On the other hand, Koilocytosis was detected in only two (2%) of the controls and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 98(98%) (Microphotographs 1-4). The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 4.84(1.02-23.02), P< 0.047. Keratinization was identified in 4(4%) of the cases and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 96(96%). On the other hand, Keratinization couldn’t be identified in all controls (Microphotograph 2). The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 9.37(0.49-176.43), P< 0.135. Inflammatory cells infiltrates were identified in 4(4%) of the cases and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 96(96%). On the other hand, Inflammatory cells infiltrates were detected in only one (1%) of the controls and couldn’t be identified in the remaining 99(99%). The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 4.12(0.45-37.45), P < 0.208, as shown in Table 2 & Figure 3. The majority of the cases with cytological atypia were identified among age group 23-32 years followed by 28-32 years, representing 7/12(58.3%) and 3/12(25%), respectively, as shown in Table 3. Moreover, most of the cases with viral infections were also found among age group 23-32 years followed by 28-32 years, representing 5/11(45.5%) and 3/11(27.3%), respectively, as shown in Table 3 & Figure 3. With regard to the duration of shisha usage, the highest atypia cases were found among those used shisha for a duration of 2-5 years representing 7/11(63.6%) followed by 6-10 and 10+ years constituting 3/11(27.3%) and 2/11(18.2%), in this order. On the other hand, the highest viral infection was detected in duration 2-5 years, representing 6/9(66.7%) followed by 1/9(11.1%) in each remaining duration, as indicated in Table 3 &Figure 4.

Variable |

Category |

Cases |

Controls |

Total |

Age |

||||

<22 years |

20 |

21 |

41 |

|

23-27 |

33 |

24 |

57 |

|

28-32 |

23 |

24 |

47 |

|

33-39 |

14 |

18 |

32 |

|

40+ |

10 |

13 |

23 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

200 |

|

Education |

||||

Basic |

25 |

28 |

53 |

|

Secondary |

16 |

15 |

31 |

|

University |

59 |

57 |

116 |

|

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

200 |

Table 1 Distribution of the study subjects by age and Education

Variable |

Cases |

|

Controls |

|

P Value |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

||

Cytological atypia |

11 |

89 |

1 |

99 |

< 0.017 |

HPV |

9 |

91 |

2 |

98 |

<0.047 |

Keratinization |

4 |

96 |

0 |

100 |

< 0.135 |

Inflammatory cells infiltrate |

4 |

96 |

1 |

99 |

< 0.208 |

Table 2 Distribution of the study subjects by cytological findings

Variable |

Atypia |

|

|

HPV |

|

|

Present |

Absent |

Total |

Present |

Absent |

Total |

|

Age |

||||||

<22 years |

1 |

40 |

41 |

1 |

40 |

41 |

23-27 |

7 |

50 |

57 |

5 |

52 |

57 |

28-32 |

3 |

44 |

47 |

3 |

44 |

47 |

33-39 |

1 |

31 |

32 |

1 |

31 |

32 |

40+ |

0 |

23 |

23 |

1 |

22 |

23 |

12 |

188 |

200 |

11 |

189 |

200 |

|

Duration of usage |

||||||

< 1 year |

0 |

7 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

5-Feb |

7 |

51 |

58 |

6 |

52 |

58 |

10-Jun |

3 |

24 |

27 |

1 |

26 |

27 |

10+ |

2 |

7 |

9 |

1 |

8 |

9 |

Total |

11 |

89 |

100 |

9 |

89 |

100 |

Table 3 Distribution of the cytological findings by age and duration of shisha usage

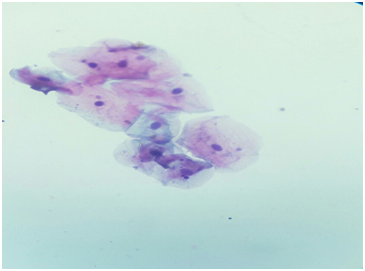

Microphotograph 1 Buccal smear taken from apparently healthy non-tobacco user. The smear showing normal buccal epithelium cells. Pap. stain X40.

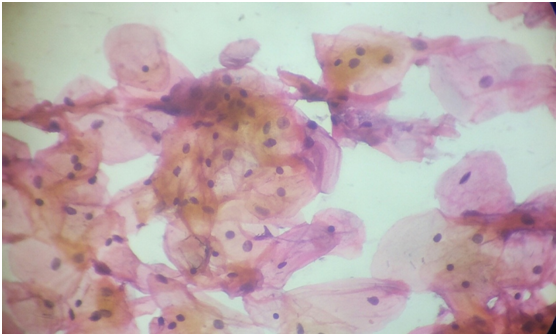

Microphotograph 2 Buccal smear taken from a person smoked shisha for 5 years. The smear showing keratinization with relatively minor cellular proliferation. Pap. stain X40.

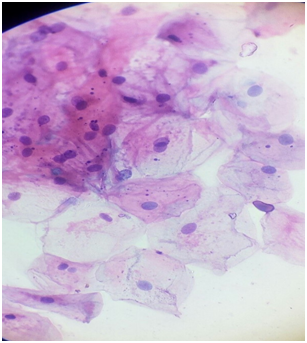

Microphotograph 3 Buccal smear taken from a person smoked shisha for 10 years. The smear showing mild cytological atypia (Hyperchromasia, increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, bi-nucleation and chromatin clumps). Pap. stainX40.

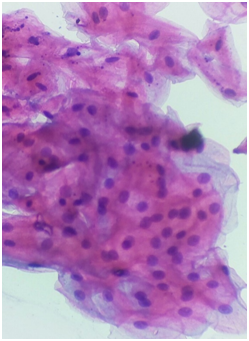

Microphotograph 4 Buccal smear taken from a person smoked shisha for 8 years. The smear showing cytological evidence of HPV infection (Koilocytes with perinuclear hallow). Pap. stainX40.

High risk HPV infection is considered as a significant risk factor for the development of oral cancer. HPV can easily transmitted through epithelium surfaces in the human body. In the present study we tested the possibility of existence of oral HPV transmission through mixed practice of shisha smoking, as well as, oral proliferative activity associated with shish smoking; which might consequently progress into oral precancerous and cancerous lesion among habitual civilian. Additionally, this study confirmed the visibility of applying oral exfoliative cytological methods for early detection of cytological atypical changes before developing into immoral cell line resulting in oral cancer. Due to the fact that smoking is considered as social stigma, all of the study subjects in the present study were males. In the present study cytological evidence of HPV infection (Koilocytosis) was identified in 9(9%) of the cases and in only two (2%) of the controls. The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 4.84(1.02-23.02), P< 0.047. Through our search in Medline and other medical electronic data base, we didn't come cross any study in this context. Therefore, this might be the first study in this regard, that indicate the possibility of oral HPV transmission through mixed shisha smoking. In the present study we examined oral epithelium cells both from buccal mucosa, which showed significant atypical proliferative changes. Cytological atypia was identified in 11(11%) of the cases and in only one (1%) of the controls. The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and (95% CI) was 12.23(1.55-96.68), P<0.017. Several reports have indicated that tobacco smoking can result in oral precancerous lesions, which can gradually progress into oral cancer, even in the absence of clinical indicators. In the evolution of malignant progression, changes happen at the cellular level before clinical changes become evident.20,21 Thus, detection of high-risk precancerous oral lesions and intervention is a major key toward reducing the incidence, prevalence, death and cost of treatment associated with oral cancer. Early alterations in the oral mucosa can be identified oral exfoliative cytology through screening of population at risk.15–23 Oral Exfoliative Cytology is well accepted by patients and it is a practical diagnostic and screening method for diagnosis and early detection of oral mucosal lesions.24 The technique has a well-known sensitivity of 94.0%, and specificity of 100%.25 Keratinization was identified in 4(4%) of the cases and none of the controls. The risk of atypia associated with shisha smoking and the OR and 95% CI was 9.37(0.49-176.43), P<0.135. Cellular keratinization, hyperchromasia and increased Nuclear/Cytoplasmic ratios usually indicate the state of malignancy transformation and thus they have a practical value in early detection and diagnosis of oral cancer patients.26 Moreover, in this study, inflammatory cells infiltrates were more frequent among cases than amongst controls, particularly, acute inflammatory cells, but the frequencies were statistically insignificant. In regard to age, although the overall effects were seemingly increased with the increase of age, which might be due to prolonged exposure, but still there considerable effect on the relatively younger population.

Mixed shisha smoking is a major risk factor for HPV transmission as well as, for the development of cytological atypia, which might subsequently progress into oral precancerous and cancerous lesions. These cytological atypical changes were found to increase tremendously among younger habitual. Oral Exfoliative Cytology is a non-invasive, easy and cheap method, therefore, it is highly suitable for screening population at risk. In our opinion tobacco smokers should undergo annual screening to detect early changes for suitable interventions.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Alobaid, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.