Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Case Report Volume 16 Issue 4

1 Specialist in Periodontology and Oral Implantology, Catholic University of Honduras, Honduras

2Specialist in Orthodontics and Maxillofacial Orthopedics, Catholic University of Honduras, Honduras

Correspondence: Karen Barahona, Specialist in Periodontology and Oral Implantology, Catholic University of Honduras, Honduras

Received: August 30, 2025 | Published: October 1, 2025

Citation: Barahona K, Soler J. Comprehensive clinical management of stage III generalized periodontitis with orthodontic rehabilitation. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2025;16(3):135-137. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2025.16.00656

Background: Severe periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting tissues, compromising both function and aesthetics. In patients with reduced periodontium, orthodontic treatment poses a therapeutic challenge, as strict inflammation control is required to prevent disease progression.

Materials and Methods: This case report describes a 22-year-old female patient diagnosed with Stage III, Grade C generalized periodontitis, with a history of poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. The treatment plan included non-surgical and surgical periodontal therapy, followed by a strict maintenance program, and later orthodontic treatment with conventional fixed appliances. Results: Periodontal control allowed the reduction of inflammation and stabilization of the remaining periodontium. Orthodontic treatment achieved space closure, proper dental alignment, and occlusal stability without compromising periodontal health. The final evaluation showed bone stability, reduced probing depths, and adequate masticatory function.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates that, with an interdisciplinary approach and a sequential treatment plan, it is possible to achieve functional and aesthetic rehabilitation in patients with advanced periodontitis and systemic comorbidities, provided that strict periodontal control is maintained.

Keywords: advanced periodontitis, interdisciplinary orthodontics, type 1 diabetes mellitus, periodontal therapy, dental rehabilitation

Severe periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the progressive destruction of the supporting dental tissues, which can lead to pathological tooth migration and compromise both oral function and aesthetics. In such cases, orthodontics may be considered as an adjunct to periodontal therapy to restore dental alignment and improve function. However, its application in patients with advanced periodontal attachment loss raises concerns regarding long-term stability and the limitations of a conservative approach. The elimination or strict control of periodontal inflammation is an essential prerequisite before initiating any orthodontic treatment.1

Orthodontic therapy, in addition to correcting malocclusions and optimizing stomatognathic function, may facilitate oral hygiene, reduce the risk of caries and periodontal disease, and improve patients’ aesthetic and psychological parameters. A functional and balanced occlusion also contributes to the prevention of temporomandibular joint overload or trauma, and when performed at the appropriate time, it may positively influence the development of both soft and hard dentomaxillofacial tissues.2,3 The interaction between orthodontics and periodontitis has been the subject of recent investigation. Evidence indicates that the mechanical forces applied during tooth movement can modulate the host’s inflammatory response to periodontal pathogens. Certain pro-inflammatory mediators may be upregulated, while others are downregulated, suggesting that the inflamed periodontal environment may respond differentially to orthodontic stimuli.4-6

Alterations in periodontal support may clinically manifest as extrusion, rotation, spacing, and pathological tooth displacement, with maxillary incisors being particularly vulnerable to migration.7 During orthodontic tooth movement (OTM), the application of forces creates areas of compression and tension within the periodontal ligament, triggering resorption and bone apposition. This remodeling process involves not only bone and periodontal ligament cells but also innate and adaptive immune responses similar to those observed in periodontitis.8,9 These findings support the need for comprehensive periodontal evaluation and strict inflammation control before and during orthodontic treatment in patients with reduced periodontium, in order to optimize biological responses and minimize the risk of further attachment loss.

The present report details a case of Stage III, Grade C generalized periodontitis in a 22-year-old female patient.10 At the initial evaluation, the patient reported no history of periodontal treatment or professional prophylaxis. Relevant systemic history included poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus (glycated hemoglobin: 11.3%), pancreatitis, recurrent episodes of glycemic decompensation, and prolonged use of multiple medications, including ultra-rapid insulin (Humalog®), Creon® 2500 U (6 capsules/day), Dexlansoprazole 60 mg (1 capsule/day), hydrochlorothiazide 12 mg (1 tablet/day), and laxatives (weekly or as needed).

Clinical periodontal examination revealed generalized periodontal pockets ranging from 4 to 7 mm, bleeding on probing, clinical attachment loss, and RT1 gingival recessions according to Cairo’s classification in multiple teeth (Figures 1–3). The initial treatment plan included oral hygiene instructions, chlorhexidine 0.20% mouth rinse (later substituted with a maintenance rinse), professional prophylaxis, and scaling and root planing in all quadrants. At the second appointment, access flap surgery was performed in the mandibular anterior and maxillary posterior quadrants (right and left), resulting in new epithelial attachment formation and reduction of pocket depths to 4 mm. The patient was subsequently enrolled in a periodontal maintenance program with follow-ups every 2 to 3 months, remaining clinically stable and suitable for orthodontic treatment.

Orthodontic evaluation revealed a normofacial biotype with a skeletal Class II Division 1 relationship, no vertical discrepancies, dental protrusion, and presence of diastemas (Figures 4–5). The periodontium was stable at the onset of orthodontic therapy. Conventional fixed appliances (Roth prescription, 0.022” x 0.028”) were placed in December 2024. The archwire sequence consisted of NiTi 0.014”, NiTi 0.018”, NiTi 0.020” x 0.020”, and NiTi 0.019” x 0.025”. Space closure was achieved using elastic chains and 0.028” stainless steel ligatures. The orthodontic treatment plan was divided into three phases: (1) alignment and leveling, (2) space closure, and (3) finishing and detailing of occlusion. The patient did not present any functional alterations of the temporomandibular joint, with a stable centric relation confirmed using Whip-Mix® articulator mounting.

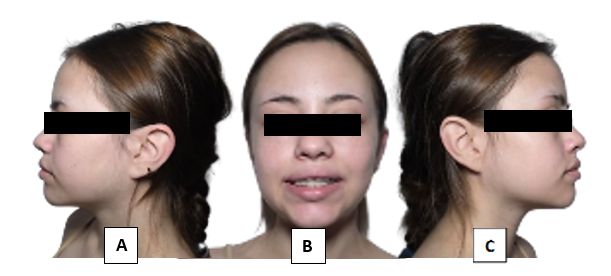

Figure 6 Clinical photographs after 8 months of orthodontic treatment (2025)

A) lateral view, B) frontal view, C) right view.

This clinical case demonstrates that, through an interdisciplinary approach and a carefully planned therapeutic sequence, it is possible to rehabilitate patients with advanced generalized periodontitis and significant loss of periodontal support both functionally and aesthetically. Thorough control of inflammation through surgical and non-surgical periodontal therapy, followed by a rigorous maintenance program, allowed the clinical stability necessary to initiate and complete orthodontic treatment without compromising the remaining periodontium.

In patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, the presence of periodontitis and high bacterial loads in the oral cavity can contribute to an increased systemic inflammatory state, making glycemic control more difficult and promoting episodes of decompensation. In this case, reducing inflammation and oral bacterial load through periodontal treatment contributed not only to preserving oral health but also to stabilizing systemic parameters, enhancing the overall response to treatment.

Final radiographic and clinical evaluation evidenced bone stability, reduced probing depths, and proper dental alignment, confirming the viability of orthodontic treatment in patients with reduced periodontium, provided it is conducted under strict periodontal control and continuous follow-up. This case highlights the importance of coordination between specialties to achieve predictable and long-lasting results in complex clinical contexts.

None.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

©2025 Barahona, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.