Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 4

1Interns Office, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Endodontics, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Oral Biology, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

5Department of Diagnostic Oral Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

6Department of Restorative Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Turki Alhazzazi, Associate Professor & Consultant in Endodontics, Chairman, Department of Oral Biology, King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry, Jeddah, ext: 22024, Saudi Arabia

Received: October 17, 2017 | Published: October 28, 2017

Citation: Bamhisoun MM, Alqahtani RS, Bogari DF, et al. Assessment of head and neck cancer knowledge and awareness levels among undergraduate dental students at king abdulaziz university faculty of dentistry. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2017;8(4):568-573. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2017.08.00294

This aim of this study was to assess head and neck cancer (HNC) knowledge and awareness levels at King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry (KAUFD), and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia to identify gaps in knowledge. An e‒questionnaire was distributed to 4th‒6th‒year dental students and interns (n=591). The questionnaire assessed HNC background, attitude toward screening, ability to recognize clinical presentation, patients’ education and management, and questions to identify the courses in which HNC knowledge was obtained. The response rate was 73.7%. Nearly half of the participants felt they had insufficient knowledge about HNC. Tobacco was identified as one of the top three risk factors by the majority of the participants, but alcohol consumption and human papillomavirus (HPV) were poorly identified. Only 52.5% of the participants completed full HNC screening, and others focused on common areas such as the tongue (46.6%) and the floor of the mouth (37.3%). Roughly half of the participants (58.4%) were able to identify the clinical presentation of malignant lesions. Almost all of the participants would manage a patient by referral, and 70.1% thought that patients should be followed up for life. This study highlighted the lack of knowledge and awareness in several aspects of the HNC area among undergraduate dental students at KAUFD. Efficient modifications should be implemented in clinical training and the curriculum of the dental school to improve knowledge and attitudes toward HNC screening and management, which will ensure early detection of the disease in our population and improve prognosis and treatment outcomes.

Keywords: KAUFD, head and neck cancer, dental student, dentistry

Cancer is one of the primary fatal health issues facing populations across the globe, and head and neck cancer (HNC) is the 9th most common cancer worldwide.1 Head and neck cancer includes malignancies that primarily arise from the lip, oral cavity, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, salivary gland, pharynx and larynx.1 Many factors increase the risk of developing HNC, but smoking and alcohol consumption have been reported to be the most related factors. However, other factors including human papilloma virus (HPV), oral health status and dietary habits are also considered to be important participating factors.2 The 5‒year survival rate of HNC is still averaging 50%, and early detection is key to a positive prognosis.3 In recent study conducted in a subpopulation of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 68% of participants had deficient of knowledge about HNC.4 In addition, 82% of the participants had never been screened for HNC.4 Dentists and undergraduate dental students play a major role in the early detection of HNC.5 Therefore, increasing knowledge and awareness and changing the attitudes of graduate dentists toward HNC management will definitely facilitate early diagnoses of the disease and improve survival rates. Only a limited number of studies have been conducted in different countries to assess the level of knowledge and awareness of HNC among undergraduate students. These studies assessed several parameters including the level of knowledge, ability to perform HNC screening, and the ability to diagnose and manage an identified case.5‒8 Although HNC education is part of the undergraduate dental student education curriculum in almost every dental school around the world, all of the reported studies unfortunately concluded that undergraduate dental students possess insufficient knowledge and a lack of clinical training to properly manage the disease. Which Improvement is urgently needed in these fields.5‒8 Therefore, the aim of the current study was to assess HNC knowledge and awareness levels among undergraduate dental students at King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry (KAUFD), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia to identify areas in which knowledge gaps exist and should be managed.

An anonymous English‒language e‒questionnaire was formulated using Google Forms. The questionnaire was uploaded on Quick Response (QR) code, which is readable by smart phones. Extra tablets were also provided for students to answer the e‒questionnaire. The e‒questionnaire was distributed among dental students (n=591) in the 2016–2017 academic year at King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The students were in their 4th‒6th years and included dental interns. The QR code was distributed after the students finished assigned subject lectures, and the dental school departments approved the distribution of the code. Answering the e‒questionnaire required roughly 8minutes. Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants. Twenty students answered the e‒questionnaire for a pilot study to assess the clarity of the questions, which resulted in a few modifications being made. The e‒questionnaire was composed of 13 questions: questions 1‒4 assessed the student’s background about HNC, questions 5‒7 investigated the student’s attitude toward HNC screening, questions 8 and 9 assessed the student’s ability to recognize clinical presentation, questions 10‒12 focused on patient education and management, and lastly question 13 asked about the courses in which HNC as a topic was covered. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee board from King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry, and the protocol of this study was in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. We used SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) for the data analysis using the Pearson chi‒squared test.

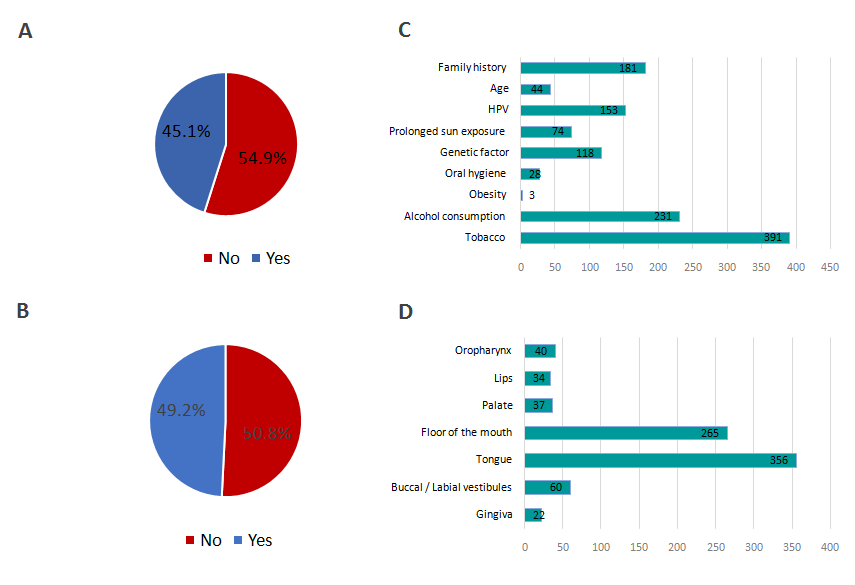

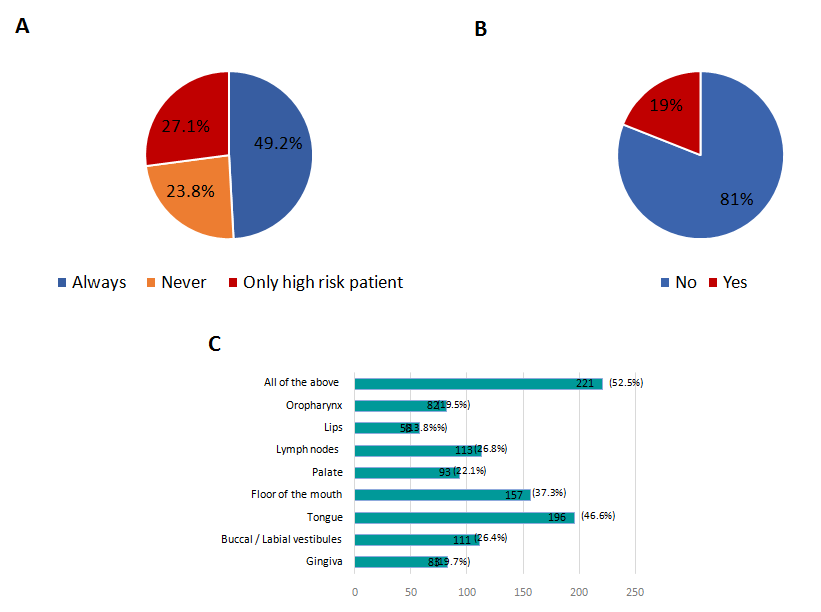

The study response rate was 73.7% (54.2% males and 45.8% females). Among the respondents, 22.6% of them were in their 4th year, 29.0% of them were in their 5th year, 23.0% of them were in their 6th year and 25.4% of them were dental interns. Regarding the students’ knowledge about HNC, more than half of the participants (54.9%) believed they do not have sufficient background about HNC (Figure 1A), and only 49.2% of the participants were familiar of the adjunctive screening tools of HNC such as brush biopsy, Tblue and VELscope (Figure 1B). Interns were more familiar with the screening tools than other students (Table 1), p<0.05). Regarding the top three risk factors, tobacco was identified by the majority of the participants (92.9%), but alcohol consumption and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) were poorly identifie0d (54.9% and 36.6%, respectively) (Figure 1C & Table 1). In addition, when the students were asked about the two most common sites of HNC, 84.6% recognized the tongue as the most common site and only 62.9% recognized the floor of the mouth (Figure 1D & Table 1). To assess the screening attitudes of the students, they were asked whether they screened all their patients for HNC and, if so, which areas they typically examined. Forty‒nine percent of the participants responded that they screened all their patients for HNC; 27.1% screened only high‒risk patients (Figure 2A & Table 1). Moreover, only 19% of the students had detected a premalignant or malignant lesion in their patients (Figure 2B). Regarding the areas of examination, only 52.5% of the students completed a full HNC screening, and others focused on common areas such as the tongue (46.6%) and the floor of the mouth (37.3%). The least common area reported to be examined was the or pharynx (13.8%) (Figure 2C & Table 1). More 4th‒ and 5th‒year students completed a full examination compared to 6th year and interns students (Table 1; p=.020). When the students were asked about HNC clinical presentation, 58.4% chose painless, an ill‒defined border and a mixed (red/white) lesion as characteristics of malignant lesions (Figure 3A). Most of the students (85%) responded that a lymph node‒associated malignancy is painless, hard and fixed upon palpation (Figure 3B). Regarding patients’ management and education, almost all the participants (98.8%) would manage a patient with pre‒malignant or malignant lesion by referral to either a maxillofacial surgeon (87.9%) or a physician (10.9%) (Figure 4A). However, only 13.8% of the students would educate their patients about HNC, and 49.6% would only educate high‒risk patients (Figure 4B). It seems that students in their 5th year and interns are more keen to educate their patients about HNC than others (Table 1; p=.001). The majority of students (70.1%) believed that patients should be followed up for life after an HNC diagnosis/treatment (Figure 4C). In terms of the curricula that covered HNC, 84% of the students reported oral pathology, followed by oral medicine (66%), oral diagnosis (62.5), oral biology (49.6%) and lastly oral histology (19.5%).

Questions |

Responses |

4th Year |

5th Year |

6th Year |

Internship |

Total |

P-value |

Do you think you have enough background about HNC |

No |

61 |

69 |

51 |

50 |

231 |

0.094 |

64.20% |

56.60% |

53.10% |

46.70% |

54.90% |

|||

Yes |

34 |

54 |

45 |

57 |

190 |

||

35.80% |

43.90% |

46.90% |

53.30% |

45.10% |

|||

Are you familiar with the adjunctive screening tools of HNC such as (brush biopsy /Tblue / VELscope ): |

No |

59 |

66 |

49 |

40 |

214 |

.005* |

62.10% |

53.70% |

51.00% |

37.40% |

50.80% |

|||

Yes |

36 |

57 |

47 |

67 |

207 |

||

37.90% |

46.30% |

49.00% |

62.60% |

49.20% |

|||

Which are the top three risk factors of HNC |

Tobacco use |

85 |

110 |

94 |

102 |

391 |

.000* |

89.50% |

89.40% |

97.90% |

95.30% |

92.90% |

|||

Alcohol consumption |

37 |

54 |

77 |

62 |

231 |

||

39.00% |

43.90% |

80.20% |

57.90% |

54.90% |

|||

Obesity |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

||

3.20% |

0.00% |

1.00% |

0.00% |

0.70% |

|||

Oral hygiene |

15 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

28 |

||

15.80% |

4.00% |

3.10% |

2.80% |

6.70% |

|||

Genetic factor |

36 |

35 |

16 |

30 |

118 |

||

37.90% |

28.50% |

16.70% |

28.00% |

28% |

|||

Prolonged sun exposure |

16 |

35 |

12 |

14 |

74 |

||

16.80% |

28.50% |

12.50% |

13.00% |

17.60% |

|||

Human Papilloma Viruses |

27 |

33 |

45 |

46 |

153 |

||

28.40% |

26.80% |

46.90% |

43% |

36.60% |

|||

Age |

9 |

20 |

6 |

10 |

44 |

||

4.50% |

16.30% |

6.25% |

9.30% |

10.50% |

|||

Family History of cancer |

43 |

59 |

25 |

52 |

181 |

||

45.20% |

48% |

26.00% |

48.60% |

43% |

|||

Which of the following are the TWO most common sites for HNC: |

Gingiva |

7 |

8 |

3 |

4 |

22 |

.002* |

7.30% |

6.50% |

3.10% |

3.70% |

5.40% |

|||

Buccal / Labial vestibules |

18 |

20 |

12 |

10 |

60 |

||

18.90% |

16.30% |

12.50% |

9.30% |

14.30% |

|||

Tongue |

78 |

102 |

84 |

93 |

356 |

||

82.10% |

82.90% |

87.50% |

86.90% |

84.60% |

|||

Floor of the mouth |

41 |

82 |

51 |

89 |

256 |

||

43.10% |

66.70% |

53.10% |

83.10% |

62.90% |

|||

Palate |

9 |

3 |

19 |

5 |

37 |

||

9.50% |

2.40% |

19.80% |

4.80% |

8.80% |

|||

Lips |

17 |

10 |

7 |

1 |

34 |

||

17.90% |

8.10% |

7.30% |

0.90% |

8.10% |

|||

Oropharynx |

12 |

9 |

10 |

8 |

40 |

||

12.60% |

7.30% |

10.40% |

7.50% |

9.50% |

|||

Have you ever detected pre-malignant or malignant lesions |

No |

87 |

99 |

78 |

77 |

341 |

.006* |

91.60% |

80.50% |

81.20% |

72% |

81% |

|||

Yes |

8 |

24 |

18 |

30 |

80 |

||

8.40% |

19.50% |

18.80% |

28.00% |

19% |

|||

Do you screen your patients for HNC |

Always |

46 |

66 |

50 |

45 |

207 |

.000* |

48.40% |

53.60% |

52.10% |

42.00% |

49.20% |

|||

Never |

31 |

35 |

15 |

19 |

100 |

||

32.60% |

28.40% |

15.60% |

17.80% |

23.80% |

|||

Only on high risk patients |

18 |

22 |

31 |

43 |

114 |

||

18.90% |

17.90% |

32.30% |

40.20% |

27.10% |

|||

Which of the following areas you usually examine when screening for HNC |

Gingiva |

17 |

14 |

17 |

23 |

83 |

.020* |

17.90% |

11.40% |

17.70% |

21.50% |

19.70% |

|||

Buccal / Labial vestibules |

20 |

22 |

22 |

37 |

111 |

||

21.00% |

17.90% |

22.90% |

34.60% |

26.40% |

|||

Tongue |

35 |

45 |

50 |

51 |

196 |

||

36.80% |

36.60% |

52.00% |

47.70% |

46.60% |

|||

Floor of the mouth |

24 |

39 |

34 |

44 |

137 |

||

25.30% |

31.70% |

35.40% |

41.10% |

57.30% |

|||

Palate |

15 |

19 |

22 |

22 |

93 |

||

15.80% |

15.40% |

22.90% |

20.60% |

22.10% |

|||

Lymph nodes |

23 |

31 |

19 |

28 |

113 |

||

24.20% |

25.20% |

19.80% |

26.20% |

26.80% |

|||

Oropharynx |

11 |

11 |

14 |

7 |

58 |

||

11.60% |

8.90% |

14.60% |

6.50% |

13.80% |

|||

Lips |

19 |

17 |

13 |

17 |

82 |

||

20.00% |

13.80% |

13.50% |

15.90% |

19.50% |

|||

All of the above |

50 |

69 |

42 |

48 |

221 |

||

52.60% |

56.00% |

43.80% |

44.90% |

52.50% |

|||

Which of the following are the characteristic features of malignant lesion: |

Painful, ill-defined border and red lesion |

44 |

22 |

13 |

16 |

95 |

.000* |

46.30% |

18.90% |

13.50% |

15.00% |

22.60% |

|||

painful, well defined border and mixed (red /white) lesion. |

11 |

5 |

9 |

6 |

31 |

||

11.60% |

4.00% |

9.40% |

5.60% |

7.40% |

|||

Painless, ill-defined border and mixed (red /white) lesion. |

27 |

83 |

66 |

70 |

246 |

||

28.40% |

67.50% |

68.80% |

65.40% |

58.40% |

|||

Painless, well defined border and white lesion. |

13 |

13 |

8 |

15 |

49 |

||

13.70% |

10.60% |

8.60% |

14.00% |

11.60% |

|||

Which of the following are the characteristic features of lymph nodes associated with malignancy upon palpating: |

Painful, soft and mobile |

15 |

14 |

8 |

9 |

46 |

0.052 |

15.80% |

11.40% |

8.60% |

9.30% |

10.90% |

|||

Painless, hard and fixed |

73 |

102 |

88 |

95 |

358 |

||

76.80% |

82.90% |

91.70% |

88.80% |

85% |

|||

Painless, soft and mobile |

7 |

7 |

0 |

3 |

17 |

||

7.40% |

5.70% |

0.00% |

2.80% |

4% |

|||

How would you manage a patient with pre-malignant or malignant lesion: |

Follow up yourself |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.069 |

0.00% |

0.80% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.20% |

|||

Inform the patient only |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

||

3.20% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

0.90% |

1% |

|||

Refer to Maxillo-facial surgeon/oral pathologist |

78 |

106 |

85 |

101 |

370 |

||

82.10% |

86.20% |

88.50% |

94.40% |

87.90% |

|||

Refer to physician |

14 |

16 |

11 |

5 |

46 |

||

14.70% |

13.00% |

11.50% |

5.20% |

10.90% |

|||

Do you educate your patient about HNC |

Always |

7 |

21 |

12 |

18 |

58 |

.001* |

7.40% |

17.00% |

12.50% |

16.80% |

13.80% |

|||

Never |

52 |

45 |

30 |

27 |

154 |

||

54.70% |

36.60% |

31.30% |

28.10% |

36.60% |

|||

Only on high risk patients |

36 |

57 |

54 |

62 |

209 |

||

37.90% |

46.30% |

56.30% |

57.90% |

49.60% |

|||

How far do you think HNC patients should be followed after diagnosis/ treatment? |

1 years |

11 |

10 |

10 |

13 |

44 |

.015* |

11.60% |

8.10% |

10.40% |

12.10% |

10.50% |

|||

10 years |

8 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

16 |

||

8.40% |

2.40% |

5.20% |

0.90% |

3.80% |

|||

2 years |

9 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

49 |

||

9.50% |

2.40% |

2.20% |

2.10% |

11.60% |

|||

5 years |

11 |

19 |

7 |

12 |

17 |

||

11.60% |

15.40% |

7.30% |

11.20% |

4% |

|||

For life |

56 |

88 |

72 |

79 |

295 |

||

58.90% |

71.50% |

75.00% |

73.80% |

70.10% |

Table 1 The survey questions and descriptive data

P<0.05 shows significant correlation.

Figure 1 Assessment of Student Knowledge: (A) Self perception about HNC knowledge. (B) knowledge regarding adjunctive screening tools. (C) Knowledge about the top three risk factors. (D) Knowledge about the two most common areas for HNC.

Figure 2 Screening attitude: (A) Attitude toward screening. (B) Previous detection of malignant lesion. (C) Areas screened by the students.

Dentists play a crucial role in detecting and diagnosing HNC. Therefore, improving knowledge, awareness, and attitudes toward HNC screening and management of undergraduate dental students will affect the long‒term prognoses of this killer disease in our community. In the current study, more than half of the participants felt that they did not have enough background about HNC. When asked about risk factors, tobacco was identified by the majority of the participants, but alcohol consumption and HPV were poorly identified. However, these two factors are considered to be on the top of the risk factor list worldwide.9‒11 This finding is in accordance with other studies in which dental students always identify smoking as a major risk factor and neglect other important factors.5‒8 The unsatisfactory level of knowledge about alcohol consumption in Jeddah and other parts of Saudi Arabia may be caused by religious and society barriers. This area should receive more awareness from our student’s educators to break this barrier.3 The tongue and floor of the mouth have been reported to be the most common sites for HNC, which is what was noted by students at Taibah University, Saudi Arabia.5 In addition, nearly half of the students surveyed here felt that they needed further information regarding HNC. This finding is consistent with what has been reported at the International Islamic University, Malaysia and the University of Dundee, UK.7,8 In our study, less than half of the students reported screening their patients for HNC. However, higher screening percentages have been reported by dental students at both University of Dundee and the International Islamic University for HNC screening.5‒7 The low screening percentage by our students, may explain the recently reported findings of Alhazzazi that 82% of his cohort reported that they had never been screened for HNC.4 The majority of our participants noted that they would refer an at‒risk patient to a maxillofacial surgeon, consistent with findings noted at the Khyber College of Dentistry, Peshawar, Pakistan.6 However, at Taibah University students tend to refer their patients to an oncologist.8 Most of our students (70.1%) agreed that HNC patients should be followed for life. This recommendation is indeed the recommendation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Such a recommendation helps with closely monitoring treatment progress and avoiding the late diagnosis of any unfortunate recurrent or secondary lesions that develop.12 Interestingly, medical students tend to be less likely to examine their patients’ oral cavities routinely and advise them about HNC risk factors compared with dental students.8 It will be interesting to conduct this comparison again at our school in the future.

This study highlighted the lack of knowledge and awareness in several aspects of HNC among undergraduate dental students at KAUFD. Efficient modifications should be implemented in the clinical training and the developing curriculum of the dental school to improve knowledge and attitudes toward HNC screening and management. Such work will ensure early detection of the disease in our population and improve prognosis and treatment outcomes.

The authors are grateful for the fund of this project by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under the grant number (G‒720‒165‒38).

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

None.

©2017 Bamhisoun, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.