Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 2

1University Côte D’Azur, Department of Dermatology, CHU Nice, France

2Vichy Laboratoires, Levallois Perret, France

3MS Clinical Research Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Correspondence: Natalia Kovylkina,Vichy Laboratoires, Levallois Perret, France, Tel +33 (0)682790705

Received: June 04, 2025 | Published: June 20, 2025

Citation: Passeron T, Kovylkina N, Deloche C, et al. Treatment of acne-induced post inflammatory hyperpigmentation using new Liftactiv B3 Melasyl. A randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2025;9(2):50-54. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2025.09.00291

Introduction: Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) follows skin inflammation or injury and is especially common in individuals with skin of colour. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl for acne-induced PIH in female subjects over three months, through a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Materials and methods: One hundred and twelve females with mild to moderate PIH were enrolled and randomized to Group A (New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl) and Group B (Placebo) and subjects used either the test treatment or the placebo serum twice daily for 3 months. The main outcome measures were improvement in post acne hyperpigmentation index (PAHPI) and Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scores, improvement in skin attributes, improvement in parameters using spectrophotometer, corneometer, tewameter, Antera, and VISIA CR. Evaluations were performed at baseline, months one, two, and three.

Results: Group A showed a statistically significant PAHPI reduction (p<0.001), with decreases of 11.69%, 35.98%, and 43.48% at months 1, 2, and 3, respectively, with distinct visual improvement observed by month 1. Similar significant improvement in IGA scores, with reductions of 19.73%, 55.10%, and 59.86% at months 1-3 (p<0.001) was observed. Group A exhibited twice the improvement of Group B at months 2 and 3, highlighting its superior efficacy. At the end of 3 months, New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl was found to be well tolerated by all participants.

Group A demonstrated pigmentary spot density reduction, as confirmed by spectrophotometer and Antera. Improvements in pigmentation, clarity, and complexion, with lighter spots, reduced imperfections, and even tone were also observed.

Conclusion: New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl demonstrated statistically significant improvements in multiple skin parameters, with early differentiation from month 1, and sustained efficacy through month 3. These findings show the efficacy and good tolerance of New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl for treating acne-induced PIH.

Keywords: post inflammatory hyperpigmentation, acne, spots, PIH, SoC, depigmentation

Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is an acquired form of hypermelanosis that arises secondary to cutaneous inflammation or injury.1–3 PIH occurs at any age and is more common in individuals with darker phototypes, especially those with Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI.4–6 The global prevalence of PIH varies, but ranges from 0.4% to 10% in African Americans and 6% to 7% in Latino patients,6 which often results from inflammatory conditions such as acne or eczema.7 It is characterized by excess production of melanin in the epidermis, and its deposition in the epidermis and/or dermis.8

Clinically, PIH manifests as hyperpigmented macules or patches. While epidermal PIH presents as light to dark brown patches, PIH with predominant deposition of melanin in the dermis presents as grey to black discolouration.6,8

Skin conditions contributing to cutaneous inflammation and subsequently to PIH include acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and lichen planus, while exogenous factors include burns, chemical peels, physical injuries, friction, radiation etc.1,5 Additionally, exposure to ultraviolet and visible light radiation further exacerbates PIH.1,9

Acne-induced PIH is a cause of concern as it has detrimental effects on quality of life and is a cause of psychosocial distress for affected individuals.2,10 It manifests as localized or diffuse brown to grey-brown macules at the site of acne lesions, which become evident after the erythema resolves.11 Recent studies have indicated that PIH is associated with stigmatization,12,13 diminished social life, poor body image, decreased self-esteem,1 and feeling of embarrassment13 as it can take several months to years to fade away.14 It accounts for 45.5% to 87.2% of dyschromias for which patients seek treatment.11

The overall management of PIH involves addressing the underlying cause, strict photoprotection, and its prompt treatment to prevent further darkening.8 Topical agents such as hydroquinone, retinoids, keratinolytics, corticosteroids and depigmenting agents are utilized for epidermal depigmentation. Topical agents when used with adjunctive therapies such as chemical peels, lasers and microneedling can enhance efficacy of procedural therapies.11,12 These procedures however, are accompanied with an increased risk of PIH especially in individuals with skin of colour.11

Melasyl™ (2-mercaptonicotinoyl glycine) is a novel depigmenting agent that acts by conjugating with melanin precursors and inhibits their conversion to eumelanin and pheomelanin pigments. Additionally, it deprives melanocytes of highly reactive melanin precursors such as dopaquinone, thus reducing its reactivity. Unlike traditional agents, it does not inhibit tyrosinase, allowing physiological melanogenesis to remain intact.15

The present study aimed to evaluate and compare the efficacy of New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl and Liftactiv serum in the management of acne-induced PIH, in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne-induced PIH.

Study design

This study is a double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled randomized study, conducted at M S Clinical Research Pvt. Ltd. Bangalore between September 2023 and April 2024. It was approved by an independent ethics committee and was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trials registry of India (CTRI/2023/10/058831). Written informed consent was obtained before initiating study-related activities.

Study population

Female subjects, between 18-50 years of age, who presented with mild to moderate facial post-acne hyperpigmentation, with all skin types (normal, oily, dry and combination), with at least 2 epidermal spots as confirmed clinically and by dermoscopy, and measurable by spectrophotometer, were included in the study. Subjects with severe acne; those using topical or systemic retinoids, immunosuppressants; or those undergoing topical or procedural treatments for PIH were excluded. Additionally, individuals with dermal PIH or other hyperpigmentary disorders such as melasma and lichen planus pigmentosus were excluded from the study.

Interventions

Enrolled subjects completed an exposome questionnaire and underwent a three-week wash-out period, during which they were advised to use the provided sunscreen (Mixa SPF 30) and a neutral serum twice daily.

On the baseline visit, imaging evaluations (Antera and VISIA CR), dermatological, instrumental evaluations and questionnaires (Lifestyle/habit, DLQI, hormonal status, cosmetic acceptability) were completed and hair samples were collected to examine hormonal factors. Subjects were randomized based on computer-generated randomization into one of two groups in a 1:1 ratio: Group A received New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl Serum, and Group B received Liftactiv serum. Subjects were given the test product to use on their whole face, focusing on the pigmented areas, twice daily, for 3 months. Furthermore, participants in both groups were instructed to apply the provided sunscreen 10 minutes after using the test products. They were advised to avoid applying any additional skincare products, undergoing facial treatments, or exposing their skin to excessive sunlight.

Similar imaging, dermatological, instrumental evaluations and questionnaires (self-assessment questionnaire, subject global assessment, DLQI) were completed on months 1, 2 and 3.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was to evaluate and compare the efficacy of New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl and Liftactiv serum in reducing acne-induced PIH, Post Acne Hyperpigmentation Index16 (PAHPI; weighted scores for median lesion size (S), median lesion intensity (I) and number of lesions (N); total PAHPI=S+I+N; score range: 6-22). Secondary endpoints were to evaluate changes in Investigator Global Assessment for pigmentation (IGA; score 0-clear of hyperpigmentation to 5- very severe hyperpigmentation), and dermatological evaluations for improvement in evenness of skin tone, skin smoothness, skin shade using shade card, Glow and Radiance (using MSCR glow and radiance scale). Crow’s feet, pores, density of pigmentary spots and contrast of spot with bare skin were evaluated using the L’Oreal atlas. Dermatological evaluation for type and number of acne lesions was recorded and skin tolerability to the test products was done at every time point.

Instrumental endpoints were to evaluate and compare improvement in colorimetric parameters by spectrophotometer and Antera, improvement in pigmentation using spectrophotometer, skin moisturization using corneometer-CM825, skin barrier function using tewameter, and dark spot using Mexameter.

Subject Global Assessment score, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and subject self-assessment questionnaires were used to evaluate subject-related endpoints.

Sample size calculation expecting a 10% dropout rate, 56 participants were enrolled in each group to ensure 50 evaluable subjects complete the study. This was sufficient to detect a difference from baseline in PAHPI at 3 months, with a standard deviation of 1.93 and 80% power.

Statistical analysis

Normality check was performed using Shapiro-Wilk test on the raw data. When data was not normally distributed, Wilcoxon signed rank- Pratt Lehman test was performed to compare each group with their baselines, and Mann-Whitney test was used to compare data between the two groups.

PAHPI: Groups A and B showed significant reduction in acne-induced PIH at months 1, 2 and 3 when compared to baseline as summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Group A showed a statistically significant PAHPI reduction (p<0.001), with decreases of 11.69%, 35.98%, and 43.48% at months 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Improvement was visually distinct by month 1 and was 1.82 times greater than that of Group B. At the end of month 3, Group A showed more than 100% improvement in PAHPI scores compared to Group B.

|

Time point |

PAHPI |

IGA |

||||

|

Mean ± SD Change from baseline of Group A (n=55) |

Mean ± SD Change from baseline of Group B (n=50) |

Group A vs Group B % variation in PAHPI scores |

Mean ± SD Change from baseline of Group A (n=55) |

Mean ± SD Change from baseline of Group B (n=50) |

Group A vs Group B % variation in IGA scores |

|

|

Baseline |

12.13 ± 2.94 |

12.02 ± 3.13 |

- |

2.67 ± 0.88 |

2.72 ± 0.93 |

- |

|

Month 1 |

-1.42 ± 1.58* |

-0.78 ± 1.33* |

81.82% |

-0.53 ± 0.5 |

0.26 ± 0.44 |

>100% |

|

Month 2 |

-4.3 ± 1.83* |

-1.72 ± 2.63* |

>100% |

-1.47 ± 0.5 |

-0.56 ± 1.01 |

>100% |

|

Month 3 |

-5.27 ± 2.87* |

-2.26 ± 3.42* |

>100% |

1.07 ± 0.26 |

2.00 ± 0.95 |

>100% |

Table 1 Summary of change from baseline PAHPI and IGA scores of Groups A and B at months 1, 2 and 3

*p< 0.05

IGA: Groups A and B showed significant reduction in IGA scores at all-time points. Group A showed statistically significant reduction in IGA scores of 19.73%, 55.10% and 59.86% at months 1, 2 and 3 respectively (p<0.001), while Group B showed 9.56%, 20.59% and 26.47% reduction at months 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Group A showed twice as much reduction in IGA scores of more than 100% at months 2 and 3, when compared to group B, highlighting its superior efficacy.

Dermatological evaluations for glow and radiance

Groups A and B showed significant improvement in glow and radiance at months 1, 2 and 3 when compared to baseline. Group A showed 35.09%, 72.90% and >100%, while group B showed 15.45%, 29.70% and 40.81% at months 1, 2 and 3 respectively in glow and radiance.

Dermatological evaluations for density of pigmentary spots, evenness of skin tone, skin smoothness, Crow’s feet wrinkles, pores, contrast of spots using the L’Oreal atlas:

Density of pigmentary spots: At months 1, 2 and 3, group A showed 15.31%, 37.76% and 51.53% reduction in density of pigmentary spots, while group B showed 7.06% at month 1 and 16.47% at months 2 and 3. Group A showed significantly higher (more than 100%) reduction in pigmentary spots than group B.

Crow’s feet wrinkles: Group A showed significantly higher (more than 100%) reduction in crow’s feet at month 2 and 3 when compared to Group B. Table 2 summarizes the results observed in the study.

|

Parameter |

Crow’s feet |

Contrast of spots |

Evenness of skin tone |

Pores |

Skin smoothness |

Density of pigmentary spots |

||||||

|

Group |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

|

Baseline |

2.24± 0.54 |

2.08 ± 0.27 |

3.67±0.55 |

3.54±0.5 |

3.76±0.51 |

3.6±0.6 |

3.36±0.59 |

3.3±0.65 |

3.47±0.88 |

3.1±0.95 |

3.56±0.6 |

3.4±0.73 |

|

Month 1 |

-0.05±0.23 |

0.0±0* |

-0.62±0.49#$ |

-0.22±0.42# |

-0.64±0.56#$ |

-0.22±0.42# |

-.031±0.47 |

-0.26±0.44 |

-0.58±0.5#$ |

-0.14±0.35# |

-0.55±0.5#$ |

-0.24±0.43# |

|

Month 2 |

-0.73±0.56#$ |

-0.24±0.43# |

-1.16±0.63#$ |

0.46±0.5# |

-1.45±0.6#$ |

-0.54±0.68# |

-1.0±0#$ |

-0.48±0.5# |

-1.18±08#$ |

-0.36±0.6# |

-1.35±0.55#$ |

-0.56±0.7# |

|

Month 3 |

-1.11±0.46#$ |

-0.48±0.5# |

-1.93±0.88#$ |

-0.7±0.81# |

-2.27±0.71#$ |

-0.94±1.15# |

1.22±0.42#$ |

-0.7±0.81# |

-2.02±0.91#$ |

-0.68±0.94# |

-1.84±0.94#$ |

-0.56±0.81# |

Table 1 Summary of change from baseline scores of crow’s feet, contrast of spots, and evenness of skin tone, pores, skin smoothness and density of pigmentary spots

# p<0.005

$ >100% improvement compared to group B

*p< 0.0999

Contrast of spots: Group A showed 16.83%, 31.68%and 52.48% reduction in contrast of spots at months 1, 2, and 3 respectively when compared to baseline, while Group B showed 6.21%, 12.99% and 19.77% reduction in contrast of spots at months 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Group A showed more than 100% reduction in contrast of spots when compared to Group B at months 1, 2, and 3.

Evenness of skin tone: Group A showed 16.91%, 38.65% and 60.39% improvement in skin tone at months 1, 2, and 3 when compared to baseline, while group B showed 6.11%, 15.0%, 26.11% improvement. Group A was more than 100% higher improvement in skin tone at all-time points when compared to group B as shown in Figure 2.

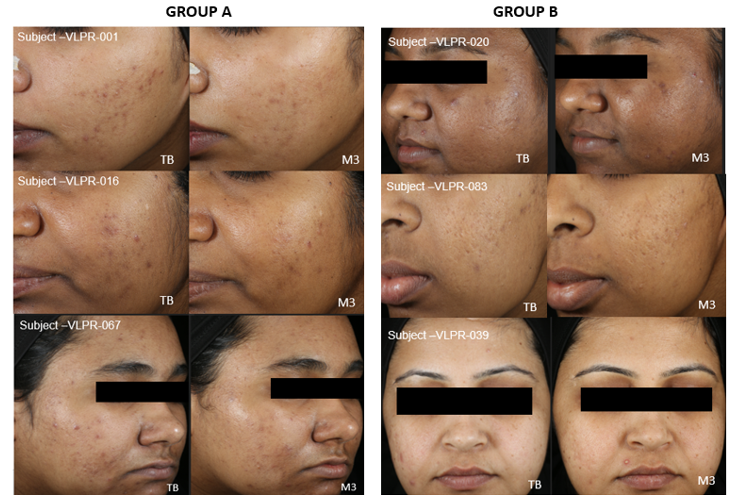

Figure 2 Images showing improvement in evenness of skin tone, reduced density of pigmentary spots in Groups A and B.

Pores: Group A showed 9.19%, 29.73% and 36.22% reduction in pores at months 1, 2, and 3 respectively, while group B showed 7.88%, 14.55% and 21.21% reduction in pores at months 1, 2 and 3. Group A showed significantly higher reduction on pores than group B; more than 100% at month 2 and 74.03% at month 3.

Skin smoothness: Group A showed 16.75%, 34.03% and 58.12% improvement in skin smoothness at months 1, 2 and 3, while group B showed 4.52%, 11.61% and 21.94% improvement at months 1, 2 and 3. When compared to group B, group A showed significantly higher improvement of more than 100% at all-time points.

Count of closed comedones: Groups A and B showed reduction in the number of closed comedones at all-time points when compared to baseline. Group A showed 27.66%, 58.56% and 79.23% reduction at months 1, 2 and 3, while group B showed 29.75%, 58.78% and 79.03% reduction at months 1, 2 and 3. The reduction in comedones was not significant between the two groups.

Number of papules: Both groups showed reduction in papules at all-time points when compared to baseline. Group A showed 38.12%, 78.03% and 93.72% at months 1, 2 and 3, while group B showed 43.23%, 85.42% and 94.79% reduction at months 1, 2 and 3.

Improvement of skin colour: Group A and B both showed significant improvement in skin colour on the forehead. Group A showed 7.16%, 13.48% and 22.20%, while group B showed 3.21%, 6.30% and 9.51% improvement at months 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Group A showed significantly more improvement that Group B at all-time points.

Instrumental assessment

Instrumental evaluations using Spectrophotometer, Corneometer, Tewameter, Mexameter and Antera are summarized in Tables 3 & Table 4. Evaluations using the spectrophotometer showed that L*of spots on the cheek, cheek L*, cheek ITA and spot ITA showed lightening in both Groups A and B when compared to baseline. At month 3, Group A showed 20.51% significantly higher improvement in spot lightening than group B. Brightness on the cheek in group A significantly improved by 0.97%, 1.70% and 2.37% at months 1, 2 and 3.

|

Instrument |

Spectrophotometer spot L* |

Spectrophotometer cheek L* |

Spectrophotometer cheek ITA |

Spectrophotometer spot ITA |

||||

|

Group |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

|

Baseline |

44.31±4.96 |

44.19±5.88 |

49.6±5.39 |

49.28±5.72 |

-1.68±16.41 |

-2.87±17.28 |

-19.81±17.53 |

-20.42±20.87 |

|

Month 1 |

0.5±0.42 |

0.42±0.19 |

0.48±0.32# |

0.48±0.23# |

1.36±1.34# |

1.41±0.91# |

3.31±2.49# |

3.33±2.80# |

|

Month 2 |

0.89±0.44& |

0.76±0.25* |

0.84±0.38# |

0.84±0.27# |

2.31±1.57# |

2.45±1.00# |

4.23±2.45# |

4.18±2.82# |

|

Month 3 |

1.34±0.48& |

1.11±0.26# |

1.17±0.45# |

1.2±0.32# |

3.28±1.60# |

3.39±1.48# |

5.25±2.66# |

4.90±2.52# |

Table 3 Summary of change from baseline scores of instrumental evaluations using Spectrophotometer for spot L*, cheek L*, cheek ITA and spot ITA

# Significant change from baseline (p<0.05), & Significant difference between groups (p<0.05), * p<0.0999.

|

Instrument |

Corneometer |

Tewameter |

Mexameter for forehead melanin |

Antera spot pigmentation |

||||

|

Group |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

Group A |

Group B |

|

Baseline |

31.47±2.44 |

32.34±1.83 |

10.25±0.24 |

10.23±0.21 |

330.74±120.89 |

314.58±131.19 |

56.38±4.85 |

64.11±10.03 |

|

Month 1 |

5.67±0.59# |

5.58±0.56# |

-0.55±0.06# |

-0.52±0.06# |

-26.56±15.93# |

-21.52±16.45# |

-0.65±0.07& |

-0.39±0.04& |

|

Month 2 |

11.54±0.79# |

11.34±0.78# |

-1.09±0.09# |

-1.07±0.08# |

-46.11±19.61# |

-43.5±21.99# |

-1.29±0.08& |

-0.79±0.06& |

|

Month 3 |

17.28±0.84# |

17.05±0.99# |

-1.64±0.1& |

-1.59±0.11# |

-65.56±20.83# |

-63.69±22.33# |

-1.93±0.1& |

-1.19±0.06& |

Table 4 Summary of change from baseline scores of instrumental evaluations using Corneometer, Tewameter, Mexameter and Antera

# Significant change from baseline (p<0.05), & Significant difference between groups (p<0.05), * p<0.0999.

Similar significant results were seen in skin hydration and reduction of forehead melanin, in both groups, when compared to baseline using corneometer and Mexameter. Group A showed 18.03%, 36.65% and 54.90% improvement in hydration to baseline, at months 1, 2 and 3. Significant reduction in skin barrier function was seen in both groups A and B, when compared to baseline and between groups.

Antera evaluation for spot pigmentation revealed significant reduction in spot pigmentation at all-time points when compared to baseline and between groups A and B. Group A showed 64.73% significantly higher reduction in spot pigmentation than group B.

Safety: No adverse events were reported in either group during the study period.

The key active ingredient in New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl Serum is Melasyl™ (2-mercaptonicotinoyl glycine). It is a novel depigmenting agent that conjugates with melanin precursors and inhibits their conversion to eumelanin and pheomelanin pigments.15 Its localized and non-cytotoxic action, combined with antioxidant properties, enables targeted pigment reduction without affecting surrounding skin, making it suitable for all phototypes, including sensitive and darker skin tones. Other ingredients include vitamin C, Niacinamide, glycolic acid and urea. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a well-established antioxidant and skin-lightening agent. It suppresses melanogenesis by chelating copper ions at the tyrosinase active site and by inhibiting oxidative polymerization of melanin precursors. Additionally, it supports collagen synthesis and protects against UV-induced pigmentation, contributing to overall skin brightness and health17,18 Niacinamide (vitamin B3) works by inhibiting the transfer of melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes, thereby reducing melanin deposition in the epidermis. It also strengthens the skin barrier, reduces inflammation, and improves skin texture, making it ideal for long-term use and combination therapies due to its excellent tolerability.19,20 Glycolic acid, a low molecular weight alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA), promotes chemical exfoliation and epidermal turnover by weakening corneo-desmosomal junctions, facilitating the removal of pigmented keratinocytes. It also down-regulates tyrosinase expression and stimulates fibroblast activity, enhancing collagen production. In higher concentrations, glycolic acid induces controlled epidermolysis and pigment dispersion, and its combination with other agents often yields synergistic depigmenting effects.21,22 Urea, known for its keratolytic and hydrating effects, contributes to depigmentation by softening the stratum corneum and promoting desquamation, which aids in the removal of melanin-containing cells. It also enhances skin texture through stimulation of collagen and hyaluronic acid synthesis, and has demonstrated efficacy in hyperpigmentation when used in multi-agent regimens.23,24

Collectively, these agents, through antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibition, pigment precursor binding, and enhancement of skin renewal, aid in treating hyperpigmentation. Their diverse mechanisms and favorable safety profiles have led to their widespread inclusion in cosmeceutical and dermatological products.

Prevention and treatment of acne-induced PIH involves a multifaceted approach comprising topical and procedural therapies. Prevention of PIH involves the use of emollients and broad-spectrum sunscreens with sun protective factor of 50+, UVA/UVB and visible light protection.25,26 The prompt and aggressive management of underlying acne in skin of colour populations using retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, dapsone and azelaic acid have proven to be effective as first-line treatment options which are now formulated as dermocosmetics.1,25 Energy-based devices, light sources and microneedling procedures are adjuncts to topical agents,27 especially for cases resistant to topical agents.

In this study, New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl having Melasyl, which contains Melasyl as the key ingredient, showed significant improvements in PIH which are in line with previous studies.15,28

The study is limited by the lack of an active control group, which may exaggerate the intervention's effectiveness. Its focus on one ethnicity restricts generalizability, as results may vary across diverse populations. Additionally, the three-month duration is insufficient to evaluate long-term effects or sustainability, necessitating further research with longer follow-up.

New Liftactiv B3 Melasyl serum demonstrated statistically significant improvements across multiple skin parameters, with early differentiation evident as early as month 1, and sustained efficacy through month 3. It reduced pigmentation, enhanced skin tone, improved skin clarity and texture, as confirmed by subjective assessments and objective imaging. These findings highlight its clinical efficacy as a potent dermocosmetic treatment option for PIH.

The authors extend their gratitude to Vichy Laboratoires for funding the study, MS Clinical research Pvt Ltd for conducting the study and participants for taking time out to participate in study related activities.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2025 Passeron, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.