Journal of

eISSN: 2572-8466

Mini Review Volume 12 Issue 2

Research Associate in Cuba, Latin American Center for Agroecological Research (CELIA), Cuba

Correspondence: Luis L Vázquez, Research Associate in Cuba, Latin American Center for Agroecological Research (CELIA), Cuba

Received: April 26, 2025 | Published: May 13, 2025

Citation: Vázquez LL. Scope of agroecology during the agroecological transition of the local food system. J Appl Biotechnol Bioeng. 2025;12(1):60-65. DOI: 10.15406/jabb.2025.12.00385

The agroecological transition towards sustainable food systems is a relatively recent topic of research. One of the challenges is to have reference frameworks to articulate the agroecological transition with the different agri-food processes that are carried out in the territories. Experiences in the agroecological transition that has taken place in Cuba over the past 30 years have led to the identification of domains within the field of agroecology for food governance, a proposal addressed in this article.

Keywords: food governance, domains, sustainable food

There is a proactive debate on the future of food at the international level. This is not a new issue, as the conventional approach to food production and supply has long been questioned in order to meet the demands of the population regarding access, nutritional value and contribution to health. However, although most of the actions carried out are aimed at sustainable food, they generally maintain a conventional methodological basis, which is why institutional innovations need to be prioritized so that food governance is also sustainable.

The predominant agricultural production model, whose main characteristic is hyper-technification to achieve higher crop yields, is based on the use of massive doses of inputs: fossil fuels, pesticides, fertilizers, hybrid seeds, machinery, water for irrigation, and a long list goes on. However, this agricultural model has not managed to solve the problem of hunger in the world population, because there are currently 800 million hungry people, according to the report “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World in 2020”.1

Food security, at the national level, means that "all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life" and has four fundamental dimensions: availability, access, consumption and utilization, and stability over time of the three previous dimensions.2 This can be considered as a first stage to consolidate during the transition towards sustainable local food systems; because security needs to be sustainable in the production and post-production processes, in which local sovereignty also needs to be consolidated.

A sustainable food system ensures food security and nutrition for all people, in such a way that the economic, social and environmental foundations that allow providing food and nutrition security for future generations are not put at risk.3

Faced with enormous economic, environmental, demographic and political challenges, agriculture and rural areas are at a crossroads and in need of profound transformation.4,5 Considering the current state of degradation of natural resources and the tolerance limits of human populations, it is not socioeconomically sustainable to try to solve food needs solely by increasing production anywhere, transporting it to different distances and depositing it in dispersed and inaccessible markets (food “security”). Rather, it is necessary to build food systems that have sustainability attributes, so that productive complementarity and territorial economic circularity are achieved for food resilience.6

In this regard, agroecology is considered one of the most promising approaches to overcome these multiple challenges and achieve resilience and sustainable development in agricultural systems,5,7,8 mainly because it is based on ecological concepts and principles that reduce dependence on external resources and, in particular, the use of chemical inputs.9

The approach to agroecology has evolved in recent years.10,11 Beyond agricultural practices at field, farm and landscape scales, agroecology now encompasses the ecological, economic, social, political and cultural aspects of food systems12–13 and is at the heart of territorial development challenges.14 It is a way of redesigning food systems to achieve ecological, economic and social sustainability10 and considers the relationship between food production and society at large.13

Agroecological transitions correspond to a progressive but systemic transformation through the greening of agriculture and food systems, implying changes in both practices and organisational aspects.15,16 These changes lead to gradual and often discontinuous trajectories of change,16 resulting in different levels of transition in the process of converting from simplified industrial agroecosystems to complex and diversified agroecological systems.10,17 It involves not only technical, productive and ecological elements, but also socio-cultural and economic aspects of farmers, their families and their community.18

In response to the food crisis that has occurred in Cuba since the early 1990s, the agroecological transition toward sustainable food systems began. This transformation has entailed the decentralization of the national food system, characterized by agricultural production in specialized mega-enterprises, toward comprehensive and diversified, locally self-managed food systems. Consequently, national food management has become territorial with a focus on sustainability, an aspect that has required institutional innovations for governance as a food system.

One contribution in this regard was the proposed scope of agroecology, which considers the following domains:19 (a) governance (policies, regulations, strategies); (b) the environment and natural resources in primary production (agricultural and livestock); (c) complementary services (consulting, training, analytical laboratories, innovation and management of inputs, among others); (d) the different post-production processes (beneficiation of fresh products, processing or transformation, collection, storage, transportation, marketing); and (e) the attitude of families and individuals towards food (education, health, communication).

This shift toward local self-management of food has seen periods of transition/slowdown due to the low social appropriation of agroecology as a science that facilitates the transformation of food systems into sustainable ones;19 for this reason, this short article aims to delve deeper into the domains of agroecology, as a contribution to its appropriation by local actors in food systems governance.

This short article is based on personal insights, drawing on experiences facilitating local development projects in different parts of Cuba, complemented by references from authors who have addressed this topic.

These experiences led to several lessons learned about the functional relationships between food governance actors at the territorial level. Its holistic analysis allowed us to describe and contextualize the domains of agroecology as axes of transitions with a vision for a sustainable future.

Scope of agroecology. Converting the conventional food model into a sustainable one is a disruptive transformation process that requires adopting new principles and methods of action. This is usually dismissed because conventional governance methods are well-established; also, because people working in municipal government departments and in the sectors are not trained or take ownership of these new approaches to facilitate systemic and participatory processes.

The agroecological transformation towards sustainable food systems is not simply the replacement of the conventional approach with a sustainable one, justified by compliance with new public policies. It means a profound change, in which the food system must be adapted to the sociocultural and environmental characteristics of the territory, a process that must necessarily be facilitated and carried out by the population itself.

When public policies for sustainable food are established, it is assumed that these are not implemented or transferred, but rather adopted or adapted in the territory as a socio-ecosystem. Likewise, it has become internationally accepted that the adoption of sustainability must be a participatory and transdisciplinary process, so that the collective added value needed for it to be truly sustainable is facilitated. Public policies, programs, and projects with sustainability approaches must appropriate the principles of agroecology and popular education so that their facilitation is efficient.

Territorial governance involves the development of collective network organization processes, where different types of interactions take place at a local level (buying and selling, information dissemination, innovation, etc.) between agents, companies and institutions, in which different multi-level coordination processes intervene.20

Many authors emphasize political commitment to food policies and social participation, in “hybrid” and multi-actor governance models, as well as in adaptation to each specific case.21,22 For DeCunto et al.,23 food governance includes participation, the integration of local initiatives in programs and policies, the development of food policies and plans, multi-sectoral information systems, and disaster risk reduction strategies.

New social practices generate, but at the same time require, new knowledge and understanding, which have requirements: their own complex and dynamic nature demands permanent learning, so that both individuals and communities, companies, government institutions, cultural organizations, etc., develop skills to face the new challenges of the knowledge society and are trained for a more positive insertion in the new global scenario.24

The practices associated with agroecology have a transformative character that implies the redesign of the entire agri-food system,25 in which the complex relationships established between ecological functioning, human well-being, innovation, governance models and bottom-up policies are integrated. In this way, agroecology imprints the socio-ecological vision on the context of agroecosystems.26,27

In the reconstruction of resilient territories, linked to a bioeconomy adapted to local resources, it is essential to strengthen the relationships and links between food production and consumption, as well as to work on rebuilding ties and communities. It is also important to recover food culture and traditional knowledge linked to local conditions, and to improve ecosystem functioning, especially in areas embedded in or close to spaces of natural value.28

Awareness of the dependence of the current food system and the negative impacts it has on the environment has driven new plans, whether strategic or spatial planning, which are formulated taking into account the functional and spatial needs that would entail the reorganization of the agri-food system in a transition towards relocalized models.28 The disruptive transformation occurring in agricultural landscapes puts pressure on territorial planning, as a fundamental component in the governance of the food system, demanding an agroecological transition towards the facilitation of functional interactions between natural ecosystems, agroecosystems and urban ecosystems, which could be considered as bio-planning of the territory.19

In this regard, López-García et al.,32 identified a structure of six areas that cross different territorial scales that arise from the intersection of two perspectives: (1) grassroots governance (new institutions and grassroots political action), (5) city-region governance (countryside-city relations), (6) Trans-local governance (networks), (3) intra-administrative governance, from the horizontal perspective (territorialized processes of cooperation between equals and (2) multi-actor governance (co-production of public policies) and (4) multi-level governance (coordination and cooperation between scales of administration, which arises from the vertical perspective (cooperation and coordination between asymmetric powers).

However, in order to initiate the agroecological transition of the existing food system, the scope of agroecology must be consistent with the functional structure that predominates in the municipalities, so that the transformational changes required for food to be sustainable are made possible from it, and this is the justification for the domains proposed by Vázquez.19

The transition towards sustainable food is not only achieved through the agroecological transformation of primary food production systems, but also requires sustainable self-management capabilities in the complementary services needed to achieve such production, decentralizing the vertical post-production system that has persisted since the conventional food model, and facilitating sociocultural learning regarding the population's attitude towards sustainable food.

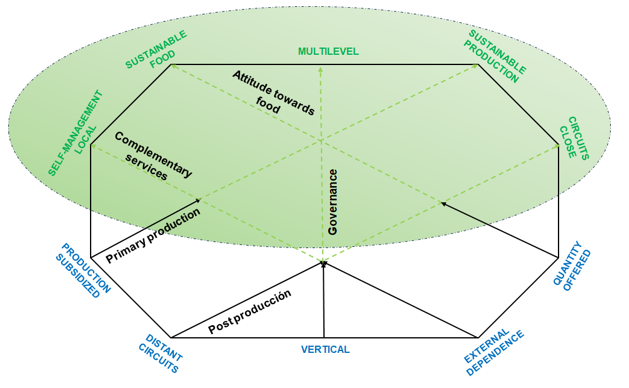

Territorial strategies for moving towards sustainable food systems must be conceived for co-action as systemic processes that interact (Figure 1); that is, achieving sustainable food does not mean moving separately through each of the different domains of agroecology, but rather requires having a vision of the future that must be designed and built coherently.

Figure 1 Domains (axes in the figure) and their agroecological transitions (path from baseline to final objective) to transform the food system into a forward-looking sustainable one (green circle).

To facilitate the agroecological transition, it is necessary for society to appropriate several elements of the systemic approach of this science: (a) agroecology for sustainability, (b) the characteristics of the context, (c) people's perception, (d) the scope of the agroecological transition in the territory, (e) the disciplines and transdisciplines involved in the agroecological transition, (f) open access to different sources of agroecological knowledge and (g) the participatory methods of agroecology for transformative action.19

Transition in the domains of primary food production and complementary services: The primary food production domain, which occurs from the production systems and productive forms to which they belong (companies and cooperatives), has moved in two main dimensions: (1st) the fragmentation of large specialized companies into cooperatives (immediate effects on: reduction in the size of productive forms, diversity of people who manage the land, recovery of the farm model, diversification of production, recovery of auxiliary vegetation structures, reconfiguration of the structural matrix of landscapes, facilitation of the functional connectivity of biodiversity, others) and (2nd) the rise of agroecology in peasant agriculture systems (immediate effects on: adoption of sustainable biotechnologies, agroecological management of soil-crop systems, integration of agriculture, livestock and forestry, productive diversification, integration of alternative energies, integration of auxiliary vegetation structures, conservation of biodiversity, dissemination of the traditional farm model towards new farmers, social valorization of peasant agriculture, among others).

To achieve the aforementioned transitions, there was a shift in the decentralization of technological innovations, which moved from the protagonism of scientific centers created for conventional agriculture to the active participation of local farmers and technicians. In addition, several universities and foreign agencies, together with civil society organizations and small-scale family farming, have valued popular education, small-scale experimentation and participatory innovation, turning agricultural territories into agroecological laboratories for producing food sustainably.

The experience of the Peasant-to-Peasant Agroecological Movement (MACaC), which encourages interaction between farmers and has spread to various farming families throughout the country,30 although it has not been able to scale sufficiently in the peasant systems themselves and towards other forms of productive organization, should be studied to identify factors that limit the appropriation of this valuable tool.31

This transformation towards participatory innovation also influenced the awakening of institutional innovation in some scientific centers, which broke conventional disciplinary barriers and began to co-innovate with farmers, obtaining impressive results regarding the design of their research and new innovative technologies, mainly on the development of microbiological bioproducts, animal traction, participatory plant breeding, urban agriculture, agroecological fruit growing, agroecological pest management, soil conservation and improvement, animal feed, integrated farms, among others.

However, most of these centres have maintained the focus of deciding on research to offer technologies and transfer them according to conventional agricultural extension methods, a situation that should be studied to reorient scientific research towards transdisciplinary studies in agroecosystems.

In fact, during the 1980s, training and technology transfer in Cuba was established as a vertical model in the agricultural sector, managed nationally by scientific and development institutions, with the collaboration of entities and specialists in the territories. This technology transfer approach, which was widely disseminated in the country associated with the concept of science, emerged from the "green revolution" model. This way of "doing science" in a centralized way in agriculture, presupposes that professional researchers know the priorities of farmers and that they adapt the technologies designed in public or private research institutions. The very division of disciplines and the specialization of knowledge excluded the possibility that farmers or clients of innovation could lead the design, implementation and dissemination of a new variety, crop or technology.32

Since the period in which conventional agriculture was consolidated, the sectors established various provincial services in the territories that complement primary production and post-production processes of food (analytical laboratories, technical advice, resource management, training, technology transfer, others), most of which depend on national scientific centers in methodological aspects and technological approach.

In general, no significant changes are observed, because knowledge management is limited to planning training on repeated topics and for program and project needs, which are carried out in classrooms equipped for this purpose and sometimes through demonstration practices in fields. They are taught by specialists from local entities, as well as others who belong to provincial and national institutions, a system that worked well for the previous model of conventional agriculture; however, it is not efficient for the agroecological transition towards sustainable systems, because they are not based on the principles of popular education, nor of agroecology.

A recent study on sustainability in agroecological knowledge management in Cuban territories31 determined that the criteria with the highest contribution rates were lectures or classes as the only form of interaction; while the largest number of criteria with the highest contribution rates were grouped in the medium contribution to sustainability, results that show a certain local autonomy and the predominance of a vertical-unidirectional action, which is characteristic of conventional training methods.

In fact, in the municipalities, there are units with different functions in the sectors of agriculture, environment, food, health, education, which perform various services; these, like civil society organizations, university campuses and municipal polytechnics, create a valuable local critical knowledge to train people to integrate self-managed devices that facilitate agroecological transformation.

The classic form of intervention in many countries has materialized in the creation of public research and extension institutions. Due to their operation under a centralized and linear model, this type of institution has been the object of multiple criticisms, questioning its effectiveness and efficiency in the generation, but above all in the dissemination of knowledge. The fundamental criticism revolves around its linear vision of the technology transfer process, in which basic research leads to applied research, then to technological development, from this to production and subsequently to commercialization, with a defined and limited role for each of the different actors: universities and research centers, extension institutes, advisors and consultants, companies and organizations, among others.33

There are (or we can rely on) theoretical and conceptual frameworks to work in cooperation between (and with) the different actors, the co-conception of innovations, such as action research, intervention research or, in a general way, collaborative research.34 It is about the birth of action research, of being able to match the will for change (of farmers and other actors) with the intention of research.35

An innovation systems approach that fits perfectly with the idea of horizontal knowledge creation inherent to agroecology is the one known as co-innovation,36 which combines the complex systems approach with social learning and dynamic monitoring of innovation projects. Co-innovation platforms include diverse actors, from producers to scientific technicians, extension workers, government representatives, technology and input suppliers, the market, etc.37

Transition in the post-production domains and the population's attitude towards sustainable food: Harvested products are collected and transported to different types of markets that exist in population settlements, mainly in urban areas. Meanwhile, during the agroecological transition towards sustainable food systems, the population's attitude towards food is also very important. In fact, these domains of agroecology are demanding a greater contribution from research for the realization of transformative actions.

The units that carry out the post-production processes (collection, transportation, temporary storage, marketing), which were created from the vertical and unidirectional approach of conventional food, have moved from national to territorial management; while, at this level, decentralization towards the communities has slowed down, where suburban cooperatives, community agriculture (organoponics, intensive gardens) and local family agriculture (plots, yards) are articulated as an inclusive local marketing system.

The centralization and verticality established by conventional agriculture and food in the system of collection, transportation and marketing of fresh food, together with various irregularities in supply and demand that have an impact on high prices, limit the sustainability of the population's access to food and influence the transitions needed to increase local capacities.

Regarding physical access to food, according to Anaya,38 there is not always a presence of food in the markets that guarantees the full satisfaction of the nutritional demands and needs of the population at all times. This fact is conditioned by several factors, for example, the seasonality of national production (70% of the crops are obtained in the winter months); the lack of adequate infrastructure for the storage, conservation and processing of these products in order to maintain a systematic supply throughout the year; and other aspects already mentioned in the previous section such as cuts in food imports.

In relation to the population's attitude towards sustainable food, the conventional criterion of considering fresh foods as products, which must be consumed under the demand for quantity and quality, persists. However, the agroecological transition must lead to the demand for foods obtained without agrochemicals, that are nutritious, biosafe and that facilitate immunological and neurological functions. The action of education, health and communication systems must contribute to the rescue of traditional food culture and educate the population in a sustainable attitude towards food intake.

It is well known that, with social development, human populations have been regrouping in urban (towns and cities), peri-urban and rural socio-ecosystems. These characteristics have contributed to the fact that today's society is made up of population conglomerates in anthropized habitats, where the quality of food and the state of health, which are still valued separately, have become important social problems, even in rural areas, where the influences of modernity have eroded food culture and traditional medication.39

Determining factors: Current food systems have developed under the influence of the globalization of the markets for technologies, inputs and energy needed to produce agricultural and livestock products, in addition to a high external dependence to meet the needs of basic grains and processed foods, which is why they have become nationally and internationally subsidized, in which the reductionist behavioral perception of society has been decisive, considering that it is the only possible solution to satisfy food needs.

Although decentralization towards territorial food systems is evident in all municipalities of the country, the demand for food according to the resident population has not been met, due to the combination of several factors that determine moments of progress/slowdown: (a) perception of key actors in favor of the conventional approach; (b) limited focus on the product in the generation and decentralization of sustainable agrobiotechnologies; (c) high external dependence on inputs and energy; (d) centralization of financing sources; (e) low recognition of the socio-ecological values of traditional peasant agriculture as a sustainable mode of production; (f) limited technical capacities to facilitate innovations that lead to agroecological transformations in the systems; (g) decontextualization and inequity in the innovation system; (h) insufficient social appropriation of agroecology; (i) public policies consistent with sustainability, but their implementation is not carried out with a sustainable approach.

Regarding the perception of key actors, different narratives coexist in the territories that confront conventional and sustainable production and marketing; which are expressed in the actions of people, entities and organizations that participate in the governance of the population's food, most of which have a significant role in the establishment of public policies, strategies and actions. The transition from conventional to sustainable food means a transcendental disruptive change, which requires institutional and technical innovations, reinforced by the "social appropriation" of agroecology, in which knowledge is shared and used by society as a whole for common action and benefit.19

Several factors can act alone or together to promote and maintain the territorial scaling of agroecology:40–43 (1) crises that drive the search for alternatives; (2) social organizations; (3) constructivist teaching-learning processes; (4) effective agroecological practices; (5) mobilizing discourse; (6) external alliances; (7) favorable markets; (8) favorable political opportunities. Although the crisis has been a necessary condition that serves as a favorable climate to search for alternatives other than the agroindustrial model, it inevitably requires a multiplicity of triggering elements for a large-scale agroecological process to begin.

Knowledge co-creation is gaining recognition and use within agroecology science, practice and the movement. It presents a compelling and adaptable approach and outcome to the increasingly complex challenges facing farmers and the agri-food system.44,45

The correspondence between the domains of agroecology and the functional structure operating in municipalities is a reference framework that facilitates food governance during the transition toward sustainable food systems.

The experiences of the agroecological transition taking place in Cuba constitute a laboratory for innovation in the governance of sustainable food systems.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Vázquez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.