International Journal of

eISSN: 2576-4454

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

1Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State. Nigeria

2Department of Environmental Management and Toxicology, Faculty of Sciences, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Correspondence: Morufu Olalekan Raimi, Department of Environmental Management and Toxicology, Faculty of Sciences, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Received: March 15, 2025 | Published: April 1, 2025

Citation: Nathaniel AM, Soberekon IJ, Gamage IE, et al. Fecundity insights: the breeding habits of Atlantic mudskippers in Ogbo-Okolo mangrove forest of saNta Barbara River, Bayelsa State Niger Delta, Nigeria. Int J Hydro. 2025;9(1):27-33. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2025.09.00400

Rationale: Fecundity estimation and reproductive biology of Atlantic mudskippers (Periophthalmus barbarus) in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria needs to be studied.

Objectives: To estimate fecundity, gonadosomatic index, and condition factor of P. barbarus and describe its reproductive biology.

Methods: P. barbarus specimens were collected from Ogbo-Okolo mangrove forest in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Length, weight, and gonad weight measurements were taken. Fecundity was estimated by the gravimetric method. Length-weight relationship, condition factor, and gonadosomatic index were calculated. Ovarian developmental stages were identified.

Results: Highest mean fecundity of 9612.7 eggs was observed in females of 10.1-12.0 cm standard length and 20.0-27.9 g weight. Length-weight relationship showed specimens were in good condition. Gonadosomatic index was higher in smaller individuals. Four ovarian developmental stages were identified.

Conclusion: P. barbarus exhibits high fecundity. Reproductive potential is greater in intermediate sized individuals compared to smaller or larger fish.

Recommendations: Sustainable management practices should be implemented to conserve P. barbarus stocks in the Niger Delta region. Further research into reproductive behavior and ecology is needed.

Keywords: morphometry, length, weight, fecundity, mudskippers, fish breeding seasonality, gonadosomatic index, Ogbo-Okolo mangrove Forest, Niger Delta

The Atlantic mudskipper (Periophthalmus barbarus) is a species of mudskipper native to the tropical Atlantic coasts of Africa, the Indian Ocean, and the western Pacific Ocean. They inhabit fresh, marine, and brackish waters, including tidal flats and mangrove forests, where they readily move across mud and sand out of the water. Mudskippers are members of the genus Periophthalmus, which includes oxudercidae gobies characterized by dorsally positioned eyes and pectoral fins that aid in locomotion on land and in water. They skip, crawl, and climb using their pelvic and pectoral fins. As semi-aquatic animals, mudskippers transition between aquatic and terrestrial environments. They are carnivorous and utilize an ambushing strategy to capture prey using their hydrodynamic tongue to suction food into their mouths. Sexual maturity is reached at approximately 10.2 cm for females and 10.8 cm for males, and they can live for about five years. Mudskippers are used by people for food, bait, and medical purposes. They are primarily found in West African mangrove swamps and brackish water bodies along the coast.1–9 The Atlantic mudskipper is found in several African countries including Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Nigeria and Ghana. Their distribution within these regions is influenced by the availability of food and shelter. Additionally, their hibernation capacity may impact their geographic distribution. The scientific name Periophthalmus barbarus originated from the Greek word’s 'peri' meaning 'around' and 'ophthalmos' meaning 'eyes,' referencing the eyes positioned dorsally that provide a large field of vision. In Greek, 'barbarus' means foreign, likely named for the mudskipper's unusual characteristics compared to other gobies.

The common name 'mudskipper' refers to their skipping movement across mudflats. They belong to the oxudercidae gobies, which inhabit both land and water. Mudskippers dig burrows for shelter and reproduction. Initially, oxudercidae was described as a monotypic family, with all members classified under the single species Oxuderces dentatus. Oxudercidae are small to medium in body size, with elongated bodies covered in smooth scales. They can be identified by their dorsally positioned eyes and pointed, canine-like teeth. Their dorsal, pectoral, and pelvic fins contain spines, varying in number. Within oxudercidae, the Periophthalmus genus comprises 12 species distinguished by having teeth in a single row on the upper jaw and a maximum of 16 spines on the pectoral fins. All Periophthalmus live in mangroves or mudflats. P. barbarus is further identified by spots or white spots on the back and over 90 scales along the sides.

p. barbarus grows up to 16 cm long. Its scale-covered body is coated in mucus to retain moisture. It has over 90 scales along the sides and stores water in its gill chambers, allowing breathing out of water. The gill chambers lack a membrane cover and can open/close through surrounding muscles or differences in partial pressure.10 In addition to retaining moisture by storing water from the surface which helps them to breathe through its skin, otherwise known as cutaneous respiration.11 They have pair of caudal fins that aid in aquatic locomotion and pelvic fins in terrestrial locomotion.12 Their pelvic fins are adapted to terrestrial-living by acting as a sucker to attach on land, their eyes are adapted closely together and can move independently of about 360 degrees, their eyes are also positioned further up on the head, enabling the eyes to remain above the water surface while their body is submerged underwater.13,14 Cup-like structures that hold water are located beneath the eye which aids in lubricating the eyes when it is on land. They have chemosensory receptors that are located within the nose and on the skin surface.15–18 While, mudskippers have a mouth that can reorient. Their short digestive system comprises an esophagus, stomach, intestine and rectum.19 The intestinal surface is folded, increasing the surface area for enhanced nutrient absorption. They have a unique olfactory organ including a 0.3 mm diameter canal near the upper lip that expands into a chamber-like sac.

Genital papillae located on the abdomen differentiate females, which have less rounded papillae, from males.20 As semi-aquatic animals, mudskippers inhabit slightly salty waters such as rivers, estuaries and mudflats. They spend most daylight hours on land in tidal regions, emerging at low tide to feed and hiding in burrows at high tide. These burrows can extend 1.5 meters deep providing refuge from predators.14,17,18 The burrows may contain air pockets for breathing despite low oxygen. Mudskippers tolerate high concentrations of industrial wastes like cyanide and ammonia in their environment.21–23 When exposed to high ammonia, they can actively secrete it through their gills even in highly acidic conditions (pH=9.0).14 They survive varied environments including different water temperatures and salinities. Hot, humid climates optimally enhance cutaneous respiration and maintain their surface body temperature between 14-35°C. Mudskippers build mud walls around their approximately 1-meter territory to maintain resources from predators. While hunting, they submerge leaving only their eyes out to sight and locate prey. They then launch onto land using predominantly their pectoral fins and catch prey in their mouth. When land predators threaten, they exhibit flight behavior by jumping into water or skipping away on mud.14,23 Therefore, the objectives are to assess the length-weight relationship and condition factor of P. barbarus, and determine its gonadosomatic index.

Study area

The Ogbo-okolo mangrove Forest of Santa Barbara River is located in Nembe local government Area of Bayelsa State, Nigeria at 4.5328oN, 6.4037oE (Figure 1). The area lies entirely below sea level with a maze of meandering creeks around the mangrove forest. Ogbo-okolo mangrove Forest of Santa Barbara River is significant in the provision of suitable breeding sites for diverse aquatic organism that abound in the area, good fishing ground for artisan fishers as well as petroleum exploration and production activities by Aiteo company.

Study site

The vegetation of the Ogbo-okolo mangrove consists of the red mangrove Rhizophora racemosa and white mangrove Avicenna Africana ranging in height from 5 to 15 meters. The main sea flows into smaller tributaries during high tide when the water is salty. At low tide, the stilt-like prop roots of mangroves are visible and the intertidal mudflat is exposed, serving as a feeding ground for mudskippers. The mudskippers dig small burrows between 3.5-6 cm in diameter around the prop-roots of Rhizophora trees. These areas serve as hideouts for Periophthalmus species. Traps will be set around these burrows to catch Periophthalmus specimens. Bacteria and microorganisms thriving in the mud produce sulfur gases, giving the mudflat a rotten egg odor. The study area has a tropical climate with average temperatures around 25°C and high humidity. Rainfall is heavy year-round, with peak precipitation from May to July averaging over 300 mm monthly as describe by studies from the Niger Delta region of Nigeria.24–31 The abundant rainfall contributes to the mangrove swamps and muddy conditions ideal for mudskippers.

Sample collection

Fish trapping method were used to collect 350 Specimen of Mudskippers Periophthalmus barbarus with standard length ranging from 5.5-11.9cm and total length ranging from 7.0-14.7cm respectively. The specimen was obtained in May 2021. The fishing gears used is hands made rubber container and basket traps woven with cane materials with a single conical in curved opened. Each basket trap was 40cm long and 30cm wide. These traps are nonselective and can catch both adults and Juveniles. The traps were set during the low tide using scattered and broken crabs likes Callinetes sapidu (marine swimming crab), Cardiosoma armatum (terrestrial crab), and Sesarma huzardi (hairy mangrove crab) was used as bait for the traps. As soon as catches were made, the specimens were removed and put in a bucket containing 5% formalin and a little water. These were later taken to the laboratory. Standard length and total length of each sample was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a measuring board and the gutted weight of corresponding sample were measured to the nearest 0.1g. Specimens were dissected and the guts were carefully removed with the aid of a forceps after dissection. The gut and the liver were weighed together to the nearest 0.1g. The standard length, gutted weight and body weight of fishes were recorded into a data sheet for data analysis. In the analysis, the Total Length (TL) of the fish was measured from the tip of the anterior the (mouth part) to the caudal fin using an improvised measuring board made from wood. Fish weight was measured with an electronic scale, to the nearest 0.1g. The mean lengths and weights of the classes were used for data analysis. The relationship between the Standard Length (SL), TL, and total body weight (W)g of the fish is expressed by the equation below:

Where K = condition factor

W= weight of fish (g)

L = Total length (TL) of fish in (cm)

While, determining the Gonado somatic index of Periophthalmus barbarus. Biometric data of SL, TL to the nearest 0.01cm and body weight measurement (TW) and Gutted Weight (GW) to the nearest 0.01g were recorded. Further laboratory analysis was carried out by opening the stomach of the specimens to determine the opvaris of Periophthalmus barbarus to ascertain the gonad stages by use of naked eye examination of gonad development stage. Six biological stages of gonad development were identified as cited by Bagenal32 Moreover, four stages of gonad development were identified in this study and the classification of gonadal stages using Udo33 methods. Each specimen ovaries and specimen gut were measured to the nearest 0.1g. Gonado somatic index (GSI) of the specimen was calculated according to El-Sayed et al.,41 method:

To determine the fecundity of Atlantic mudskipper Periophthalmus barbarus an unbiased sample of the specimen were obtained. Gonad stage IV and V were used in the fecundity estimation. The specimen with gonad stage IV and V were sorted out and the standard length measured to the nearest 0.01cm and gonad weight to the nearest 0.01g, the ovaries of each is removed and stored in specimen bottle containing 3% formalin and later place in plastic petri-dishes which were agitated at interval to ensure the eggs were separated from their connective tissue and spread after adding little water in the petri-dishes. Fecundity was estimated by taking the weight of the egg follow by the weight of subsample by Bagenal32 to the nearest 0.01g.

Sum of eggs in subsamples x Total weight of egg

Total weight of subsample

The assessment of the length-weight relationship of Atlantic Mudskipper P. barbarus is shown below

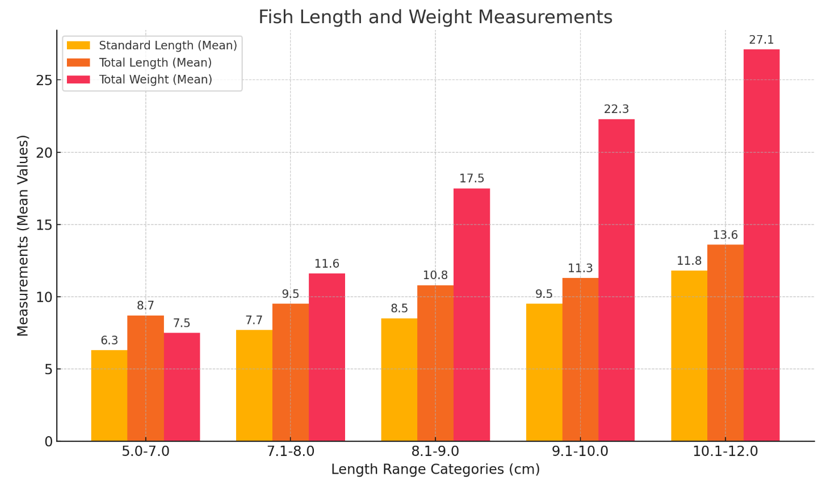

Table 1 and Figure 2 shows the observed data on fish measurements revealed that the Standard Length ranged from 5.0 to 12.0 cm, with mean values increasing progressively across size groups: 6.3, 7.7, 8.5, 9.5, and 11.8 cm. Correspondingly, the Total Length ranged from 7.0 to 14.9 cm, with mean values of 8.7, 9.5, 10.8, 11.3, and 13.6 cm. The Total Weight spanned from 3.4 to 30.9 g, with mean values of 7.5, 11.6, 17.5, 22.3, and 27.1 g. This data indicates a consistent positive correlation between the standard length, total length, and total weight across the size classes.

|

Standard length (cm) |

Total length(cm) |

Total weight (G) |

|||

|

Range |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

|

5.0-7.0 |

6.3 |

7.0-9.0 |

8.7 |

3.4-10.0 |

7.5 |

|

7.1-8.0 |

7.7 |

9.1-10 |

9.5 |

10.1-15.0 |

11.6 |

|

8.1-9.0 |

8.5 |

10.1-11.0 |

10.8 |

15.1-20.0 |

17.5 |

|

9.1-10.0 |

9.5 |

11.1-12.5 |

11.3 |

20.1-25.0 |

22.3 |

|

10.1-12.0 |

11.8 |

12.6-14.9 |

13.6 |

25.1.30.9 |

27.1 |

Table 1 Shows the length – weight relationship in P. barbarous

Figure 2 Illustrating the mean values of Standard Length, Total Length, and Total Weight for each length range category. The bars represent the respective means for each measurement, with the categories labeled clearly on the x-axis.

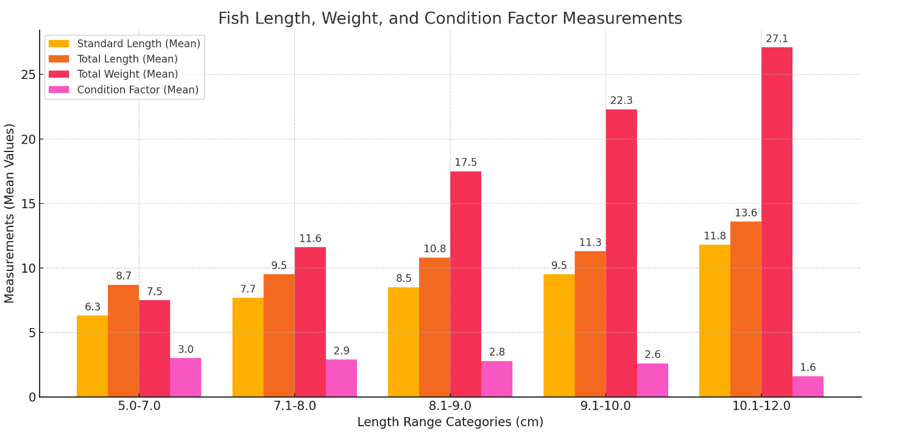

Table 2 and Figure 3 shows the data on fish measurements and condition factors that shows the Standard Length ranged from 5.0 to 12.0 cm, with mean values of 6.3, 7.7, 8.5, 9.5, and 11.8 cm. Corresponding Total Length values ranged from 7.0 to 14.9 cm, with mean values of 8.7, 9.5, 10.8, 11.3, and 13.6 cm. Total Weight ranged from 3.4 to 30.9 g, with mean values of 7.5, 11.6, 17.5, 22.3, and 27.1 g. The Condition Factor showed a decreasing trend across size groups, with mean values of 3.0, 2.9, 2.8, 2.6, and 1.6. This suggests that as the fish grew larger, their relative weight in relation to their length declined.

|

Standard Length (cm) |

Total Length (cm) |

Total Weight (G) |

Condition Factor |

|||

|

Range |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

Range |

Mean |

|

|

5.0-7.0 |

6.3 |

7.0 - 9.0 |

8.7 |

3.4-10.0 |

7.5 |

3 |

|

7.1-8.0 |

7.7 |

9.1 – 10 |

9.5 |

10.1-15.0 |

11.6 |

2.9 |

|

8.1-9.0 |

8.5 |

10.1- 11.0 |

10.8 |

15.1-20.0 |

17.5 |

2.8 |

|

9.1-10.0 |

9.5 |

11.1- 12.5 |

11.3 |

20.1-25.0 |

22.3 |

2.6 |

|

10.1-12.0 |

11.8 |

12.6- 14.9 |

13.6 |

25.1.30.9 |

27.1 |

1.6 |

Table 2 Relationship of length and weight to condition factor in P. barbarous

Figure 3 Shows the mean values of Standard Length, Total Length, Total Weight, and Condition Factor across the length range categories.

|

Number of specimen examined |

Length (cm) |

Total body weight (G) |

Stages of maturation |

|

|

Standard Length Range |

Total Length Range |

|||

|

4 |

7.0 - 8.0 |

8.0 -10.0 |

4.0 - 10.0 |

II |

|

19 |

8.1 - 9.0 |

10.1 - 11.0 |

10.1 - 15.0 |

III |

|

18 |

9.1 - 10.0 |

11.1 - 12.0 |

15.1 - 20.0 |

IV |

|

5 |

10.0 – 12.0 |

12.1 – 14.0 |

20.1 - 27.5 |

V |

Table 3 Relationship of length and body weight to stages of Gonad Maturation in P. barbarus

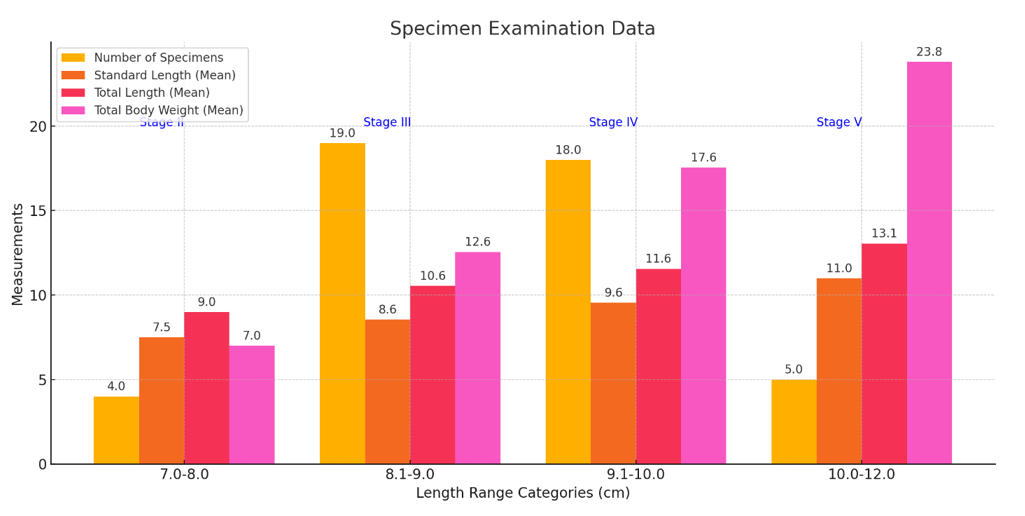

Table 3 and Figure 4 specimens revealed specimens’ variations in length, weight, and maturation stages. A total of 4 specimens with a Standard-Length range of 7.0–8.0 cm and a Total Length range of 8.0–10.0 cm weighed between 4.0 and 10.0 g, corresponding to maturation stage II. Nineteen specimens with Standard Lengths of 8.1–9.0 cm and Total Lengths of 10.1–11.0 cm weighed 10.1–15.0 g and were at stage III. Eighteen specimens with Standard Lengths of 9.1–10.0 cm and Total Lengths of 11.1–12.0 cm weighed 15.1–20.0 g, reaching stage IV. Finally, 5 specimens with Standard Lengths of 10.0–12.0 cm and Total Lengths of 12.1–14.0 cm weighed 20.1–27.5 g, corresponding to maturation stage V.

Figure 4 Display the number of specimens, mean values of Standard Length, Total Length, Total Body Weight, and their corresponding stages of maturation.

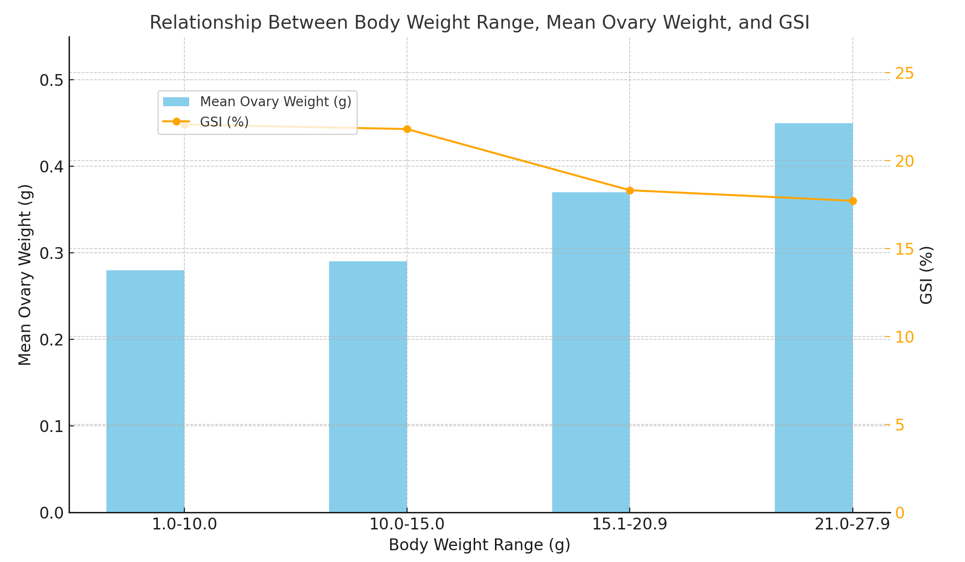

Table 4 and Figure 5 revealed body weight, ovary weight, and gonadosomatic index (GSI) shows that specimens with a Body Weight Range of 1.0–10.0 g had a mean ovary weight of 0.28 g and a GSI of 22.06. For those weighing 10.0–15.0 g, the mean ovary weight increased slightly to 0.29 g, with a GSI of 21.80. Specimens in the 15.1–20.9 g range had a mean ovary weight of 0.37 g and a GSI of 18.32. Lastly, specimens weighing 21.0–27.9 g had the highest mean ovary weight at 0.45 g, but the GSI further declined to 17.72. This trend suggests that while ovary weight increases with body weight, the relative reproductive investment (GSI) decreases.

|

Body weight range (g) |

Mean of ovary weight(g) |

GSI |

|

1.0 - 10.0 |

0.28 |

22.06 |

|

10.0 - 15.0 |

0.29 |

21.8 |

|

15.1 - 20.9 |

0.37 |

18.32 |

|

21.0 – 27.9 |

0.45 |

17.72 |

Table 4 Gonadosomatic Index (GSI)

Figure 5 Shows illustrate the relationship between body weight ranges, mean ovary weight, and the Gonadosomatic Index (GSI). The blue bars represent the mean ovary weight (g) for each body weight range, while the orange line plot highlights the GSI values corresponding to these ranges. This figure 5 effectively demonstrates the trends and interplay between body weight, ovary weight, and reproductive health indicators.

Table 5 and Figure 6 shows the fecundity data for examined specimens showing a relationship between size, weight, and reproductive potential. For 3 specimens with Standard Lengths of 7.0–9.0 cm, Total Lengths of 8.0–10.0 cm, and weights of 4.0–15.0 g, the mean fecundity was 7428.8, with a range of 5741.2–9766.3. Four specimens with Standard Lengths of 9.1–10.0 cm, Total Lengths of 11.1–12.0 cm, and weights of 15.1–20.0 g had a higher mean fecundity of 9612.7, ranging from 5484 to 14570.5. Finally, 3 specimens with Standard Lengths of 10.0–12.0 cm, Total Lengths of 12.1–14.0 cm, and weights of 20.1–27.5 g showed a mean fecundity of 8070.6, with a range of 5048–12818. This indicates a general increase in fecundity with size and weight, although variations exist within the ranges.

|

Number of specimen examined |

Length in (cm) |

Total body weight (G) |

Fecundity |

||

|

Standard Length Range |

Total Length Range |

Mean |

Range |

||

|

3 |

7.0 - 9.0 |

8.0 -10 |

4.0 - 15.0 |

7428.8 |

5741.2- 9766.3 |

|

4 |

9.1 - 10.0 |

11.1 - 12.0 |

15.1 - 20.0 |

9612.7 |

5484-14570.5 |

|

3 |

10.0 – 12.0 |

12.1 – 14.0 |

20.1 - 27.5 |

8070.6 |

5048-12818 |

Table 5 Relationship of Fecundity in P. barbarus to length and body weight

Length-weight relationship of Atlantic mudskipper, Periophthalmus barbarus were standard length ranging from 5.0-11.9cm SL, total length ranging 7.0-14.9g and the body weight between 3.4 - 30.6g body weight (BW). The condition factor values greater than one indicates the Periophthalmus barbarus specimens were in good physical condition. Condition factor decreased as fish size increased (Table 1 and 2), aligning with the finding that condition factor is inversely related to length. The estimated allometric coefficient (b) from the length-weight relationships fell within the expected range of 2.0 to 4.0 reported for most fish.34 The b value reflects that weight increases curvilinearly relative to length. Overall, the length-weight relationship parameters estimated in this study for P. barbarus were consistent with typical ranges reported for other fish species. This provides evidence that the sampled population had normal growth patterns and physiological condition. However, Siddik et al.,35 reported isometric growth of A. bato from a southern coastal river of Bangladesh. But varies with the findings in Lagos lagoon, mudskipper, Periophthalmus papilio which was grouped into unsex, males and females with size ranging from 30.0-190 mm TL and weighing between 0.5 and 65.3g BW. There was size variation across the three groups through unsex, 32-158mm; males, 69-180mm and females, 60-190mm total length.

Females attained higher growth and maturity at 69mm TL and males at 60mm TL in the study, males were significantly heavier in weight but shorter in body length than the females. Lawson36 also contradicted with 102mm and 105mm total length at maturity which he reported for females and males respectively. Udo33 also reported isometric (b is equal to 3) length weight relationship for both sexes of this species. However Abdoli et al.,37 estimated values is between 2.10 and 2.86 for both sexes for three species of mudskipper in their study in the coastal areas of the Persia Gulf in Iran. Similar trends were observed in the specie by Lawson36 who reported values between 2.56 and 3.50 in the coastal areas of Selangor, Malaysia. A positive correlation values of r = 0.9385 (unsex), 0.9684 (males) and 0.9784 (females) showed there was a strong correlation between the total length and body weight measurements of the fish, meaning the fish increase with body weight as it grows in total length. This may be more genetical than being ecological. Strong correlation between fish body size and otolith weight of a related species Periophthalmodon schlosseri was also reported by Sarimin et al.,38 The parameters of length-weight relationship are influenced by a series of factor including season, habitat, gonad maturity, sex, diet, stomach fullness, health of the individuals in their natural habitats as well as the treatment of specimens and preservation techniques the condition factor of P. barbarous were found to be greater than one (1) which indicates that the specimen were relatively healthy.

However, this study showed that condition factor decreases with increase in size of the fish. The naked eye examinations of the gonads of P. barbarous, forty-seven (47) specimen that have eggs, four stages of gonad development were identified in this study. These includes Stage II Early developing or virgin stage ll which ovary is very small firm and pale-white, stage III Late developing or maturing stage - ovary is small graining orange-yellow heavy network of vessel appear laterally on the surface of ovary wall, stage IV matured stage - ovary is yellow, large and selling the body cavity, ripe or gravid stage – ovary is yellow, large with contour walls turgid, distend body cavity, eggs are clearly distinct. Gonadosomatic index (GSI) is higher in body weight ranging 1.0 to 10.0g with 22.06 (GSI) and lower in body weight ranging from 21.0 to 27.9g with 17.78 (GSI) increase with increase in body weight but decrease in mean of ovary weight (Table 4). This showed that Atlantic mudskipper Periophthamus barbarus is highly productive between May and June in the study area this is contradicted with observation made by Atiqullah et al.,39 on Pomadasys stridens which range from 0.801 to 9.124. Lawson, (2011) who reported that (GSI) values of the fish varied between 0.01 and 0.48% in males and 0.11-8.40% in females. Higher GSI values indicate a better wellbeing for the fish, this difference in values can be attributed to the combination of one or more factors including habitat, area, season, gonadal condition, sex, health, preservation methods and differences in the size and type of the specimens caught. fecundity in P. barbarus (Table 5) showed that fish with standard length range from 9.1 - 10.0cm and weight ranging from 15.1 - 20.0g have the highest mean fecundity of 9612.7eggs, but specimens range from 10.1-12.0 standard length and weight ranging from 20.0-27.9g are more fecund than those smaller or bigger than the bracket which have fewer eggs. This means fecundity estimated for the fish with this size range 9.1 to 10.0cm TL and 15.1 to 20.8 g W, are more fecund. This showed higher fecundity contributed to body weight. The fecundity of the species increased with fish length and body weights. This is in line with an observation made by Mfon and King40 who suggest the egg production capacity of the gobiid mudskipper.41–43

The study on Atlantic mudskippers, P. barbarus, in the Ogbo-okolo mangrove forest demonstrated that reproductive output is associated with body size. Specimens with a standard length range of 9.1-10.0 cm and weight 15.1-20.0 g exhibited the highest mean fecundity at 9,612.7 eggs. Fish within the size range of 10.1-12.0 cm standard length and 20.0-27.9 g weight showed greater fecundity compared to smaller individuals, indicating that higher fecundity accompanies larger body weight. Overall, the fecundity of P. barbarus increased with fish length and body weight, which aligns with trends observed for many fish species. Larger females tend to produce more eggs due to having greater energy reserves for gamete production. The higher fecundity of intermediate sized P. barbarus may reflect an optimal balance of energy allocation for growth versus reproduction. Smaller individuals may invest more in somatic growth, while larger fish experience diminished returns on egg production. This study provides baseline data on the reproductive biology of P. barbarus, an important component of mangrove ecosystems in the Niger Delta region. The findings can inform sustainable management efforts for this species. Further research over broader geographic and temporal scales would clarify drivers of variability in fecundity and other reproductive parameters. Investigating the relationship between female body condition, environmental factors, and reproductive output could provide additional insights into the ecology of P. barbarus.

Atlantic mudskippers (P. barbarus) are economically and ecologically important components of Niger Delta mangrove ecosystems. This study found the fecundity and reproductive potential of P. barbarus populations in Bayelsa state is connected to adult body size, with implications for sustainable management. Overfishing and habitat loss threaten the sustainability of this fishery. To prevent declines in fish stocks, reproductive output, and future harvests, policy makers should implement science-based regulations on P. barbarus fishing. Required actions include:

Urgent efforts are needed to balance economic demands for P. barbarus with maintenance of its ecological role. Sustainable management informed by research will provide long-term social, economic, and environmental benefits.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this research work, the following recommendations were made:

The findings highlight the significant fecundity of P. barbarus, with a peak observed in females of intermediate size. Additionally, the study identifies variations in gonadosomatic index among different size categories, shedding light on the reproductive potential of the species. These insights underscore the importance of sustainable management practices to conserve P. barbarus stocks in the Niger Delta region, emphasizing the need for further research into its reproductive behavior and ecological requirements to inform effective conservation strategies and ecosystem management. Thus, graphically it is represented (Figure 7).

Statements and declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant competing interests to disclose.

Life Science Reporting

No life science threat was practiced in this research.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the development of the manuscripts including study conception and design, material preparation and data collection and analysis, and the first draft writing. All authors read and commented on previous versions of the manuscript and they approved the final manuscript.

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Dr. Morufu Olalekan Raimi as well as all anonymous reviewers, for feedback and discussions that helped to substantially improve this manuscript.

Preprint version

Ayibatonyo Markson Nathaniel, Ilemi Jennifer Soberekon, Igoniama Esau Gamage, Akayinaboderi Augustus Eli, Morufu Olalekan Raimi (2024) Fecundity Estimation of Atlantic mudskipper Periophthalmus barbarus in Ogbo-Okolo mangrove Forest of Santa Barbara River, Bayelsa State Niger Delta, Nigeria. bioRxiv 2024.02.01.578404; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.01.578404.

The authors declare no competing interest.

©2025 Nathaniel, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.