International Journal of

eISSN: 2381-1803

Review Article Volume 18 Issue 5

Chair of Childrens’ Health Defense Australia Chapter, Australia

Correspondence: Robyn Cosford, Chair, Children’s Health Defense Australia, Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle (retired), Director Northern Beaches Care Centre, 337-341 Barrenjoey Rd Newport NSW, Australia

Received: October 24, 2025 | Published: November 12, 2025

Citation: Cosford R. Spikeopathy, the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway, dysautonomia and nicotine: a narrative review. Int J Complement Alt Med. 2025;18(5):192-199. DOI: 10.15406/ijcam.2025.18.00748

It has been noted that current smokers have more favourable outcomes with Covid-19 infections, and that the spike protein shares some sequence homology with snake venom neurotoxins which bind to nicotinic cholinergic receptors. As the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway has been implicated in Covid-19 disease, it has been hypothesised that nicotine may provide some symptomatic benefit in spike- protein related diseases. However the actions of nicotine are neither physiologic nor specific to the α7nAChR and carry significant side effects. Therefore alternative means of activating the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway need to be sought.

Keywords: Spike protein, spikeopathy, α7nAChR, nicotinic cholinergic receptors, Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway, nicotine, autonomic nervous system, parasympathetic nervous system, vagus nerve, dysautonomia, vagal nerve stimulation, cholinergic agonists, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, lifestyle, herbs, diet.

α7nAChR, alpha 7 nicotinic cholinergic receptors; CAP, cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway; nAChR, nicotinic cholinergic receptors; PACVS, post-acute vaccination syndrome; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; PNS, parasympathetic nervous system; CNS, central nervous system; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; DVC, dorsal vagal complex; DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; AP, area prostrema; BBB, blood-brain barrier; Ach, acetylcholine; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; mAChR, muscarinic cholinergic receptors; GABA, gamma--aminobutyric acid; NETS, neutrophil extracellular traps; EAS, extended autonomic system; HPA axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; CVAD, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy; HRV, heart rate variability; PCVS, post covid vaccination syndrome; ME/CFS, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; GR, glucocorticoid receptors; VNS, vagal nerve stimulation devices; EAP, electroacupuncture; tVNS, transcutaneous VNS; PEMF, pulsed electromagnetic frequency; AChE, acetylcholinesterase

Following on from the recognition that current ( but not long-term, chronic) smokers had reduced hospitalisation and adverse effects from acute Covid infections, and that there is a degree of homology between a particular amino acid sequence in the spike protein and snake venom which binds to the α7nAChRs of the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway, it has been proposed and popularised that nicotine is helpful to counter the side effects of spike protein and inflammation, as found in for example Post-Acute Covid Vaccination Syndrome. However it is not so simple.

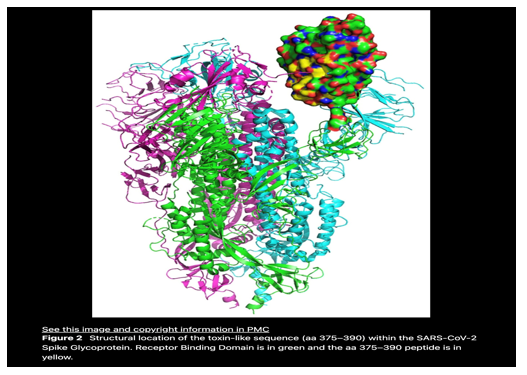

The observation that current smokers did not fare as badly as anticipated was popularised initially by Konstatinos Farsalinos, well known as a prominent researcher in e-cigarettes.1 He and his team performed in silico studies to demonstrate a region near the receptor binding domain of the spike protein that bound to the α7 nAChR, the key receptors for the Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway (CAP).2 This region has a degree of homology in its amino acid sequence with the alpha- neurotoxin of 3 finger snake venom toxins, first demonstrated to bind to nicotinic cholinergic receptors. The nicotinic receptors of the cholinergic pathway were first discovered by the action of nicotine binding: hence the term ‘nicotinic’. The natural binding agent was later discovered to be acetylcholine and related molecules like choline and phosphatidyl choline (Figure 1, 2).

Figure 2 from:2 Nicotinic cholinergic system and COVID-19: In silico identification of an interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and nicotinic receptors with potential therapeutic targeting implications.

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and the vagus nerve

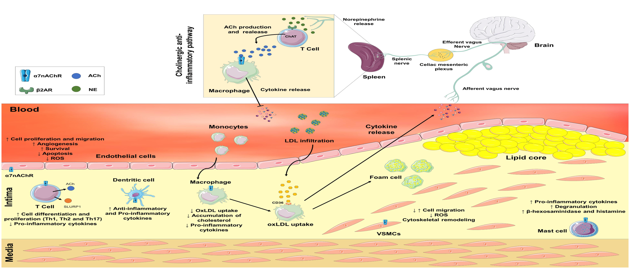

The CAP is ubiquitous around the body, with receptors both neuronal and non-neuronal, and both intra- and extra-cerebral. They are present in the immune system: lymphocytes (T and B cells), monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils and mast cells, but also adipocytes, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, platelets and epithelial cells of the intestine and lung. As a result, the CAP is now believed to play a central role in immune homeostasis. Neural conduction is rapid, capable of providing instantaneous modulatory input to region of inflammation and can also modulate output based on sensory information obtained from various parts of the host. The influence of the CAP is thus fast and integrated with respect to general status of host, as compared to the chemokine and cytokine diffusible anti-inflammatory network which is slow, non-local and dependent on concentration gradients. The specific receptors for this anti-inflammatory pathway are of the α7 nAChR type: a homeric pentamer of 5 units of the a7 subtype. In the brain, the a7nACHr are found predominantly in the hippocampus, however the predominant nACHr in the brain is the A4b2 subtype. The α7 nAChR subtype occurs throughout the immune system, on macrophages, mast cells, but also endothelial cells.

As the spike protein has been demonstrated to have a widespread distribution in the body post injection, and the nAChRs seem to be implicated in the pathophysiology of severe COVid-19 via various mechanisms including impairment of the CAP, this same mechanism could also explain the breadth and severity of symptoms experienced in long COVID and COVID-19 vaccine injuries. Post-acute vaccination syndrome (PACVS) shows failure to clear spike protein and virus, with uncontrolled immune activation and sequelae, recombinant spike protein has been shown to persist for at least 6 months post injection in some 50%, there is increased load with each subsequent injection and a recent preprint reports persistent circulating vaccine- produced spike proteins at over 700 days since the previous injection. This is an understandable catalyst for the hope that nicotine may be clinically useful in this regard.

The CAP is innervated by then vagal nerve as part of the parasympathetic nervous system which is distinct from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The modulation of inflammatory and immune response via the central nervous system (CNS) is through the vagal nerve, a bi-directional communication between immune and nervous systems. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1 activate receptors in the afferent vagus nerve fibres to signal into the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) of the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) which includes the area prostrema (AP) and the dorsal motor nucleus (DMN). The NTS provides sensory input to the CNS about the inflammatory status in the peripheral tissues and the DVC mediates autonomic function of cervical, thoracic and abdominal regions. As the AP is the site where the blood- brain barrier (BBB) is ‘leaky’ and specialised neurons are activated, systemic inflammation is also signalled there by cytokines or toxins. The transmission of efferent signals, predominantly from the DMN then modulates the inflammatory response, both directly to provide local responses through receptor on lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells, fibroblasts and keratinocytes for example, and via the coeliac ganglion and coeliac nerve to the spleen to provide a systemic response. Acetylcholine (Ach) released by the vagal nerve in the coeliac mesenteric ganglia activates postsynaptic α7nAChR on adrenergic neurons of the splenic nerve which then activates adrenergic receptors on splenic CD 4+ T cells: this stimulates ACh synthesis by the splenic T cells interacting with α7nAChR located on adjacent macrophages which then significantly and rapidly inhibits release of macrophage tumour necrosis factor, and other proinflammatory cytokines, but not macrophage secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. The CAP thus acts overall to reduce inflammation, including reduction of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, while promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Neuronal and non-neuronal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChR) are involved in the pathological process of atherosclerosis. From.3

Vagal nerve action goes beyond the activation of the CAP however, as vagus nerve activity is reduced in response to hyperinflammation and a cytokine storm, thus allowing sympathetic activation of the heart rate and blood pressure. In contradistinction, vagus nerve efferent stimulation reduces blood pressure and heart rate and inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in various inflammatory disorders. Loss of parasympathetic tone in general has been noted to predate activation of the SNS which then promotes dysautonomia and exacerbates the inflammatory effects of nAChR blockade, particularly in the nervous system, with microglial and mast cell activation and release of proinflammatory factors with neuronal tissues. A current conceptualisation of the cytokine storm as in acute severe COVID -19 infection is thus that cholinergic dysfunction together with direct inhibition of both peripheral and central nAChR by SARS -CoV-2 spike protein induces hyperinflammation and immunopathogenesis and that proinflammatory cytokines cross the BBB and inhibit central anti-inflammatory nAChR with subsequent neuroinflammation amongst other mechanisms. Neuroinflammation and dysregulated central nAChRs then stimulate sympathetic discharge with the development of an unregulated sympathetic storm with dysautonomia. This then triggers oxidative stress and hyperinflammation by an increase in the generation of reactive oxygen species and further release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Dysregulated nAChRs on immune cells in addition allows the release of proinflammatory cytokines which furthers the development of a cytokine storm.

The nicotinic acid receptors

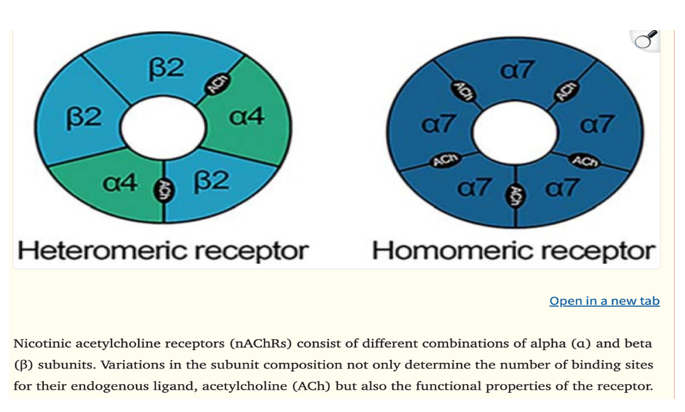

Cholinergic receptors are of 2 distinct types: the nicotinic (nAChRs) and the muscarinic (mAChR). The nAChRs are fast, ligand- gated ion of the "cys-loop” ligand-gated ion channel superfamily and are composed of five proteins symmetrically arranged around the channel. This receptor group includes the GABA (A and C), serotonin, and glycine receptors. In comparison, mAChR are not ion channels, but instead are slower metabotropic channels and belong to the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors that activate other ionic channels via second messenger cascade.

Currently, alpha (α2-α10) and beta (β2-β4) subunits have been identified in the CNS. The most commonly expressed nAChR subtype in the CNS at 90% is the α4β2* receptor, a heteromic receptor which is characterized by a high-affinity for ACh and nicotinic agonists and specialised for rapid electrochemical signal transduction. In comparison, the α7nAChR is a homomeric α7 receptor, apparently involved in both rapid ionotropic and slower metabotropic signaling but with low- affinity Ach binding.

Of all the receptor types, the α7 homo-pentamer is the most studied, with unique physiological and pharmacological properties. It is expressed at high levels in the hippocampus and hypothalamus and is the key nAChR in non-neuronal tissues such as cells of immune system as distinct to synaptic transmission. These α7 receptors are not strictly receptors for acetylcholine but respond also to choline which is the ubiquitous precursor to acetylcholine. Of note with respect to the question of the use of nicotine, there is a marked propensity of the neuronal α7 nAChRs to rapidly desensitize in the presence of agonists, notably nicotine, and α7 nAChR agonists frequently demonstrate inverted U-shaped curves in cognitive tasks demonstrating a dose dependent effect and issues with chronic or repeated dosing (Figure 4).

Figure 4 From:4 Early life stress, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and alcohol use disorders.

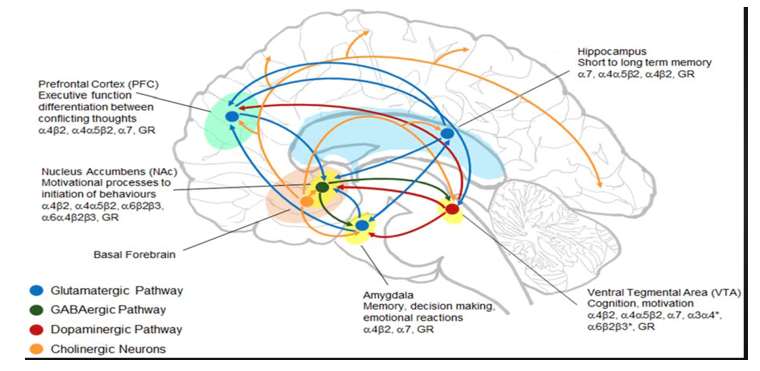

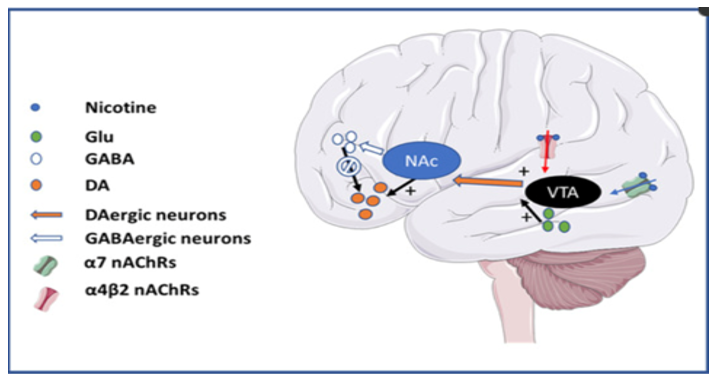

The nAChRs of the brain are primarily localized at presynaptic, perisynaptic, or somatic sites and Ach is released in a relatively diffuse manner. It functions primarily as a modulator of neuronal excitability and subsequently modulates the release of various neurotransmitters including glutamate, gamma--aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and Ach itself. Presynaptic and preterminal nicotinic receptors enhance neurotransmitter release for ACh, dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, glutamate, GABA, while there is a small minority of postsynaptic nAChRs involved in fast synaptic transmission. There are also perisynaptic or nonsynaptic nAChRs which modulate many neurotransmitter systems by influencing neuronal excitability. Nicotinic receptors thus play important roles in development and synaptic plasticity and nicotinic mechanisms participate in learning, memory and attention. These receptors thus play crucial roles in modulating presynaptic, postsynaptic, and extrasynaptic signaling, undergird the involvement of nAChRs in a complex range of CNS disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, Tourette´s syndrome, anxiety, depression and epilepsy, and the neurological symptomatology of spikeopathy.5 The critical role of nAChRs activation in modulating neuro-immune pathways has thus been recognized and investigated as an effective therapeutic in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammatory diseases (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are located within brain structures involved in modulating alcohol addiction and stress. nAChRs are found within the mesolimbic pathway (hippocampus, prefrontal cortex (PFC), nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala and ventral tegmental area (VTA)). These regions also express glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and participate in glutamatergic (blue), GABAergic (green), dopaminergic (red) and cholinergic (orange) neurotransmission. From:4

Nicotine

As nAChRs have been implicated in spikeopathy, interest was turned to the use of nicotine directly as an agonist to these receptors and its use has been popularized. Nicotine is a naturally occurring pyrrolidine alkaloid and a potent parasympathomimetic. It is considered the most addictive and pharmacologically active substance amongst the over 8000 chemicals present in tobacco products and is a strong competitive agonist with acetylcholine for nicotinic AChRs. Nicotine alters physiological processes of cells expressing nAChRs with profound systemic effects on many organs including lungs, kidneys, heart, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, mediated through effects on epithelial, endothelial, and fibroblast cells. It contributes to releasing growth factors, modification of extracellular matrix, dysregulated growth, and angiogenesis.

The effects of nicotine on the immune system are widespread and initially anti-inflammatory and thus may explain the observed protection of current tobacco smokers to COVID-19. However it becomes proinflammatory in higher doses and/or chronic dosing. It inhibits dendritic cells, the major ‘professional’ antigen – presenting cells, to decrease the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1β, IL10, IL12, TNF-α inhibition of Th1 polarization, IFN-γ production), to prevent cell apoptosis in low doses but to promote apoptosis in high doses. It has a dual role in macrophages which is dose dependant, and proinflammatory if already infected or at higher doses in which cases the macrophages switch to the M1 proinflammatory phenotype. This duality is also seen in the effects on neutrophils and mast cells. Neutrophils are activated via nAChRs and peroxynitrite generation with increased production of IL-8, stimulation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and release of intracellular granule components. The initial positive effects of pathogen control by these mechanisms are countered by pro-inflammatory effects and disease enhancement if the stimulus for NET production (in this case, nicotine) continues. Mast cells demonstrate a similar dual effect from nicotine, with suppression of the delayed phase of activated mast cells via α7/α9/α10 nAChRs, the inhibition of activation of mucosal mast cells via a7 nAChRs and the induction of the expression of cytokines (Th1 and Th2 types). However nicotine and other strong nAChR agonists demonstrate dose dependent effect of either histamine liberation or suppression of IgG activation of mast cells.

Nicotine has marked effects within the CNS and activates the nAChr receptors within the CNS. Dopamine release particularly is activated, with well acknowledged reward- pleasure effects. However chronic nicotine use results in rapid inactivation of the receptors and downregulation, the decreased dopamine release resulting in tolerance, dependance and addiction.

Epidemiological studies in the early 1960s gave the first evidence of an inverse correlation between smoking and the incidence of Parkinson’s disease. Nicotine neuroprotection in the brain and spinal cord is mainly mediated via α7nAChRs and α4β2 receptors. Nicotine crosses the BBB but the presentation of nicotine to receptors is even more diffuse than to systemic receptors, and slower by several orders of magnitude. It is also more prolonged as it is not rapidly reversed by metabolism. This nicotine affects all different nAChR subtypes in brain to varying degrees, with up to a 30x higher affinity to α-7nAChRs than ACh. The conformational dynamics of nicotine binding is also different, with smaller transient and more sustained responses and a measurable 'smoldering' steady-state current from α4β2 receptors. Nicotine delivered slowly, via a patch or pill has relatively little synchronized receptor activation. Instead, the receptors equilibrate between multiple conformational states which predominantly favors desensitization and also decreases receptor responses to endogenous cholinergic stimuli. The α4β2* receptors are directly affected by chronic exposure to nicotine and are the key receptors implicated in nicotine dependance which is a very likely outcome in chronic nicotine usage for any reason (Figure 6).

Figure 66 Schematic diagram showing key nuclei and pathways involved in addiction with strong participation of nAChRs. Nicotine binding to ∝7 and ∝4β2 nAChRs at the ventral tegmental area (VTA) promotes the initiation of addictive behaviour by favouring the release of dopamine (DA) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc).

Nicotine also has significant systemic side effects. There are negative effects on insulin resistance and glucose metabolism and nicotine itself increases blood sugar levels by alteration of energy metabolism. Hyperglycemia then inhibits nAChR activity via a negative feedback loop involved in nicotine dependence. There are also cardiovascular adverse effects including acutely raised heart rate and blood pressure, and platelet aggregation, contributing to plaque growth and thrombosis. Nicotine induces dyslipidaemia, endothelial activation, angiogenesis, vascular SM cell proliferation, and macrophage activation to M1type which produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, nicotine also alters the expression of endothelial genes, can cause endothelial dysfunction which is of particular relevance in the situation of spikeopathy which itself entails endotheliitis; and indirectly affects the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) to favor vasoconstriction and the development of endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammatory disorders.

While the theory of spike protein interaction with nAChR is attractive and is supported by amino acid sequence analysis and in silico studies, in vitro experimental competitive ligand-binding competition assays has demonstrated that mutually exclusive binding of SARS-CoV-2 and cholinergic ligands to human α-7nAChR is unlikely to be relevant aspect of inflammatory processes. These studies demonstrated that components of the spike protein had minimal competitive action in displacing α-bungarotoxin from receptor sites and that the S1 domain itself had no measurable effect on α-7nAChR channel function. Conversely, another study using a peptide of the neurotoxin-like region of SARS -CoV2 identified that this moderately inhibits α3β2, α3β4, and α4β2 subtypes, while both potentiating and inhibiting α7 nAChRs, the action of which was enhanced by nicotine.7 It appeared that the binding site of the glycoprotein was not identical to the binding site of ACh, but that it acted allosterically to alter the state of the ACh receptor. In this study, nicotine pretreatment enhances the SARS-CoV-2 glycoprotein modulation of α7 nAChR responses resulting in enhanced potentiation via a mechanism that resensitizes nicotine desensitized receptors, raising the concern that physiological processes modulated by α7 nAChRs, such as the immune system and the cholinergic anti-inflammatory response, may be further compromised in tobacco users who are infected with SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, studies have indicated that the Omicron, the dominant strain of COVID-19 at the time of the paper is attenuated in virulence at least partially as a result of decreased ability of the Omnicron SARS-CoV-2 spike-I -protein to bind to the human α7nAChr.8 It would appear that the spike protein binding to the α7 nAChRs may not be a significant contributor to the spike protein related disease processes and hence the benefits of nicotine exerted via these receptors may be minimal.

The autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system innervates all organs of body to maintain biological homeostasis at rest and in response to stress through an intricate network of central and peripheral neurons. It is traditionally viewed as consisting of the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system. However, more recent research into the role of the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems has led to a change of nomenclature to the “extended autonomic system (EAS)”.

The EAS is essentially a ‘stress system’ with recognition of the roles of the sympathetic adrenergic system, with epinephrine as the key effector; the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis; arginine -vasopressin; and the Reticular Activating System, with angiotensin II and aldosterone as main effectors. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory and sympathetic inflammasome pathways adds to this complexity. The central autonomic network first delineated as the Chrousos/Gold “stress system” regulates these systems.

The term ‘Dysautonomia’ covers a range of clinical conditions with different characteristics and prognoses including Reflex Syndromes, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, Myalgic Encephalitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension and Carotid Sinus Hypersensitivity Syndrome. Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy (CVAD) is the currently commonly used term to define dysautonomia with impairment of sympathetic and/or parasympathetic cardiovascular autonomic nervous system: if present, it implies a greater severity and worse prognosis in various clinical situations. CVAD is thus a malfunction of the cardiovascular system caused by the deranged autonomic control of circulatory homeostasis and might affect one-third of highly symptomatic patients with COVID-19/post COVID/post Vaccination.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is prone to neuroinvading via the lung along the vagus nerve up to brainstem autonomic nervous centers involved in the coupling of cardiovascular and respiratory rhythms. The brainstem autonomic network allows the SARS-CoV-2 to trigger a neurogenic switch to hypertension and hypoventilation and may act in synergy with preexisting dysautonomias and an inflammatory “storm”. The dysautonomia characteristic in acute severe COVID-19 is as a result of several proposed mechanisms including: direct tissue damage, CAP and immune dysregulation, hormonal disturbances, cytokine storm, persistent low-grade infection and iatrogenic from medications and hospital/ICU admission. This acute dysautonomia itself increases mortality risk due to intrinsic effects on respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological systems. Dysautonomia with a significant drop in vagal cardiac modulation has been well documented associated with acute SARS-Cov-2 infection using Heart Rate Variability (HRV). Many of these mechanisms are directly related to spikeopathy.

Nicotine has been trialled in acute COVID but there has been no apparent benefit in clinical trials in acute COVID. Nicotine dosing prior to inoculation with SARS-CoV-2 intranasally in mice was shown to reduce likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 RNA neuro-invasion and associated pathology, however, a DBPCCO multicenter trial in mechanically ventilated patients with Covid pneumonia concluded that nicotine patches, 14 mg daily for a maximum of 30 days, did not reduce mortality, days of ventilation or rates of anxiety, depression, PTSD or insomnia 8 weeks after nicotine tapering. There is no apparent benefit of nicotine in acute severe COVID-19 seen to date.

WHO has defined as Post-COVID-19 (PCS/PACS) the condition which occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Dysautonomia and chronic inflammation are common symptoms of this ‘Long COVID’. A recent study of health care workers using Heart Rate Variability as a measure of autonomic nervous system cardiac modulation, found sustained sympathetic cardiac modulation and diminished vagal cardiac modulation during the first 30 days after COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 associated autonomic imbalance in the post-acute phase after recovery of mild COVID-19 resolved 6 months after the first negative SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab, however a significant proportion reported long-term symptoms not apparently related to cardiac autonomic balance. The vaccination status was not reported: many may instead represent Post Covid Vaccination Syndrome (PCVS) rather than purely PACS.

PCVS /PACVS is a chronic disease triggered by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with or without a history of COVID-19, with an estimated prevalence of 0.02%. It has a phenotype of acquired autonomic dysfunction which overlaps with various established multisystemic dysautonomia syndromes including Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), POTS, fibromyalgia/chronic pain syndrome, small fiber neuropathy and mast cell activation syndrome. PACVS presents predominantly as malaise and chronic fatigue in >80% of cases with overlapping clusters of (i) peripheral nerve dysfunction, dysaesthesia, motor weakness, pain, and vasomotor dysfunction; (ii) cardiovascular impairment; with (iii) cognitive impairment, headache, and (iv)visual and acoustic dysfunctions also frequently present. Many of these people fit the criteria for ME/CFS and dysautonomia syndromes. There is considerable overlap in self-reported symptoms between PACS and PCVS and shared exposure to SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein in the context of inflammatory responses during infection or vaccination: it shares symptomatology with PACS, which is thought to be due to common pathogenic mechanisms of spike S1 protein persistence. Battarcharjee et al, from the Yale School of Medicine found that people with PCVS had significantly higher circulating S1 levels compared with the control group with elevated levels of spike (S1 and full-length S) in circulation up to 709 days after vaccination among a subset with PVS, even in those with no evidence of detectable SARS-CoV-2 infection.9

A possible role for nicotine?

Dysautonomia and persistent inflammation is characteristic of PCVS, persistent spike protein has been demonstrated and involvement of the CAP can be postulated. Considering the possible role of nicotine, it has been trialled in several neurodegenerative diseases with variable and in-consistent results, and acute, low dosing of nicotine been trialed in the context of PACS and PCVS and is being widely promulgated in social media. One published series of 4 case studies, patients presented with 'long COVID', were nicotine naïve and had no significant co-morbidities. The intervention was a 7.5mg nicotine patch mane for 7 days: only minor adverse effects were noted and all 4 patients were reported as having significant and rapid recovery which was sustained when re-viewed 3 to 6 months later. No further published or planned studies using nicotine could be found at the time of writing.

CAP dysregulation is a part of the pathogenicity of the spike protein and spike-related symptoms and support for the CAP is thus indicated. Direct agonist stimulation by potent agents eg nicotine give initial acute benefit but is inappropriate for chronic treatment as it does not mimic the physiologic effects of normal CAP function. In the short term, acute dosing of nicotine may have a beneficial anti-inflammatory effect particularly for CNS and mast cell activation, but enthusiasm must be counteracted by known risk of dependance and addiction, cardiovascular adverse effects and effects for diabetics and those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or liver dysfunction should recurrent dosing be considered.

Modulating the autonomic nervous system

With regards to the SNS, it is a question of balance. The function of the SNS – ‘flight, fright, fight’ system – is commonly conceived as being for high arousal, active states as compared to the PNS which is viewed as the ‘rest, digest, repair’ system, suggesting an association between PNS activity and social, relational and restorative processes. However, the systems do not function in a continuum but independently. The effect of this coordinated activity is highly variable in both context and in individuals. ANS activity is a core and central component of motivation, emotional and stress responses and there are marked individual differences in autonomic responses to high arousal states which are powerful indicators of vulnerability and resilience to mental and health problems as evidenced by different HRV under stress.

HRV has been used for decades as a surrogate marker for PNS tone and vagal function in patients with cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases and inversely correlates to markers of inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease, cardiovascular risk factors, autoimmune disease and traumatic brain injury. Reduced HRV correlates with immune dysfunction and inflammation, cardiovascular disease and mortality, attributable to the downstream effects of a poorly functioning cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex as a result of chronically poor vagal tone.

Encountering and managing stressors such as occur in daily life elicits autonomic responses with consequences for emotional functioning and well-being. It has been well documented that the 3 years of COVID-19 pandemic resulted in high levels of perceived stress throughout society and across countries, both as a result of COVID messaging itself but also effects of lockdowns, masking and economic effects. This apparent psychological stress response is itself a marker of alteration of homeostatic biological responses.

Some aspects of the relationship between stress and biological responses are mediated via HPA axis control of glucocorticoid and pro-inflammatory cytokine release. HPA axis activation following stress exposure results in the release of cortisol by the adrenal cortex, a significant regulator of the flight, fright, and fight response. Activation of the SNS triggers release of proinflammatory cytokines notably IL-6 via α2-adrenoreceptor activation on immune cells, with a feed-forward loop in which IL-6 potently activates HPA axis, further increasing SNS activity. Once the stressor is removed, cortisol binding to the glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the hippocampus and hypothalamus will inhibit further release of glucocorticoids and cytokines and the sympathetic drive will quieten.

In chronic stress, the persistent activation of HPA axis results in downregulation of GRs, GR-mediated signalling in the hippocampus is blunted with subsequent glucocorticoid resistance and loss of cortisol suppression of inflammatory responses. The chronically activated HPA axis has reduced hippocampal mediated regulation further contributing to cortisol dysregulation and uncontrolled proinflammatory cytokine release. Stress itself can thus trigger neuroinflammation. Stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders are associated with immune system activation/inflammation, high sympathetic tone, and corticotrophin-releasing hormone hypersecretion by the hypothalamus, all consistent with insufficient glucocorticoid-mediated regulation of stress hyperresponsiveness.

Considering treatment with nicotine in PACS/PACVS, there is a background CAP disruption which may be partially the result of direct spike protein interaction with nAChR. There are other apparent nicotine anti-inflammatory effects not the result of antagonizing spike action in this regard, demonstrated SNS dysregulation with loss of vagal tone and excess activation resulting in excess inflammatory cytokines. There is a need to be wary of nicotine dosing and frequency with significant side effects and risk of dependency so alternative means of modulating the ANS need to found (Table 1).

|

Modulating autonomic nervous systems |

References |

|

|

1 |

Lifestyle measures |

1. 139,140,141,142 |

|

2 |

HRV biofeedback |

2. 144,144,145 |

|

3 |

Forest bathing |

3. 146 |

|

4 |

Vagal nerve stimulation |

4. 147,148, 149, 150, 151,152,153,154 |

|

5 |

Electroacupuncture |

5. 155 |

|

nACHR agonism |

||

|

1 |

Dietary: solanacae |

1. 157, 158, 159, 160 |

|

2 |

Choline |

2. 164,165,166 |

|

3 |

Phosphatidylcholine |

3. 167, 168, 169, 170, 171 |

|

4 |

Choline alphoscerate |

4. 172, 173, 174,175 |

|

5 |

Citicholine |

5. 176 |

|

6 |

EGCG |

6. 177 |

|

7 |

Genistein |

7. 178 |

|

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors |

||

|

1 |

Pyridostigmine |

1. 181 |

|

2 |

Bacopa monniera |

2. 183 |

|

3 |

Huperzine A |

3. 184 |

|

4 |

Moringa oleifera |

4. 187,188 |

|

5 |

Ginger |

5. 186 |

|

6 |

Cyperus rotunda |

6. 186 |

|

7 |

Lavender |

7. 189 |

|

8 |

Oregano |

8. 189 |

|

9 |

Thyme |

9. 189 |

|

10 |

Quercetin |

10. 191 |

|

11 |

Kaempferol |

11. 191 |

|

12 |

Bacillus products |

12. 194 |

Table 1 Alternative methods of modulating the autonomic nervous system10

There are many possible modes of intervention to modulate the ANS. Lifestyle changes for example, are easy to implement. ANS modulation can be achieved by such measures as positive emotions meditation, deep diaphragmatic breathing, laughing and massage. Tai Chi and Qi Gong are similarly effective, both traditional gentle forms of movement with controlled breathing shown to increase vagal tone and balance sympathetic outflow. ‘Forest bathing' or increasing outdoor green exposure also been demonstrated to increase vagal tone and reduce sympathetic tone as evidenced by the reduction of blood pressure, lowering of the pulse rate, increasing power of HRV, improving cardiac-pulmonary parameters and metabolic function, inducing a positive mood, reducing anxiety levels, and improving the quality of life.

Vagal tone can also be increased by HRV- biofeedback monitoring of slow-paced breathing techniques. As previously mentioned, HRV variability, indexed as standard deviation of normal-to -normal heartbeat intervals is predictive in all- cause mortality and of prognosis post-acute myocardial infarction and cancer. With regards to spikeopathy, higher HRV predicts greater chances of survival in acute COVID-19, especially in patient’s aged 70 years and older, independent of major prognostic factors, whereas low HRV predicts admission in the first week after hospitalization. The use of biofeedback devices to enhance HRV and thus vagal tone is likely to also positively impact on other spikeopathy-related conditions.

Vagal nerve stimulation devices (VNS) may also be of benefit. Previously developed for intractable epilepsy, VNS at low frequencies by implantable devices has demonstrated some benefit in number of inflammatory disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, Rheumatoid Arthritis, migraine and fibromyalgia. Recently, non-invasive methods of transcutaneous VNS (tVNS) at two different anatomical locations been developed: at the cymba conchae of ear (trigeminal vagal nerve) or at the (cervical vagal nerve). These are now been trialled in growing number of pilot studies for various musculoskeletal and pain conditions. VNS via auricular stimulation has been tested in acute COVID-19 patients and shown to reduce proinflammatory markers and increase anti-inflammatory markers. It may positively influence the condition of these patients by suppressing inflammatory cytokine levels, especially IL-6 as a result of activation of the CAP, however a difference in clinical outcomes did not seem apparent. Electroacupuncture (EAP) has been demonstrated to also stimulate the vagal nerve: EAP at acupuncture point ST36 on the hind limb of mice functions via the vagal adrenal axis to enhance vagal nerve function, but is yet to be documented in spikeopathy patients.

Pulsed Electromagnetic Frequency (PEMF) devices have a higher profile than tVNS and operate via the cervical vagal affferents. They have been demonstrated to result in improved HRV as a marker of PNS activation and a recently published DBPCT of cervical vagal stimulation by a portable PEMF device has demonstrated improvements in sleep and anxiety consistent with effects on parasympathetic tone. Thus VNS/ PEMF may also prove adjunctive in ANS modulation.

In addition to physical methods, numerous foods and nutrients have been found to enhance cholinergic function. Nicotine, for example, is naturally occurring pyrrolidine alkaloid found in small amounts in foods especially the Solanaceae family (tomatoes, potatoes, eggplant), the highest being eggplant and tomatoes. It is also found in the Brassica family (Brassica oleracea), including cultivars of cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, collards and kale, all of which contain measurable amounts of nicotine. Nicotine extracted from Brassica oleracea natural food sources is effective as an anti-inflammatory compound at low dosage for rheumatoid arthritis for example; dietary supplementation with Solanaceaea fruit and vegetables are demonstrated to reduce risk of Parkinson's disease and the supplementation of an extract, anatidine with nicotine-like properties with respect to inflammation, has demonstrated benefit in osteoarthritis pain and inflammation.

Choline is involved in the biosynthesis of the brain phospholipids sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine, and the biosynthesis of ACh by the action of choline acetyl transferase. It binds specifically to α7 nAChRs but not α4β2 receptors, unlike nicotine and also exhibits neuroprotective properties but at a lower potency -about 3 orders of magnitude – and only about 40% the level of cytoprotection of nicotine. It is an essential brain nutrient for cholinergic neurotransmission and can be sourced from the diet and by de novo synthesis. Dietary choline intake has been demonstrated neuroprotective over time and promotes improved cognitive function. In analysis of the Framingham Offspring Cohort data, past choline intake was significantly associated with changes in white matter hyperintensity volume seen in MRI of the brain, while cognitive function was affected by concurrent choline intake. Sources of choline include eggs and lecithin particularly, organ meats, salmon, beef, edamame, and shitake mushrooms.

Phosphatidyl choline is a choline precursor, with potency and effects similar to choline in nAChR binding. A mixture of neutral lipids and phospholipids, essential components of CNS and especially cellular membranes, it is a natural emulsifier synthesized in plant and animals. Phosphatidyl choline is found as food predominantly in soy lecithin and egg yolk. It appears to enhance neuronal development, has demonstrated positive effects in patients with cerebrovascular disease and might decrease the risk of developing APOE4-associated Alzheimer’s dementia (AD). In a small, brief concept study of phosphatidylcholine and computer based cognitive training in PACS/ PCVS patients with cognitive impairment, there was a trend to improvement in all groups but with no statistical significance for the intervention groups. Nonetheless, cholinergic precursors choline and phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) are probably limited in enhancing brain levels of ACh.

There are other phospholipids involved in choline biosynthetic pathways- CDP-choline, choline alphoscerate and phosphatidylserine which have been demonstrated to clearly enhance ACh availability or release. These have provided modest improvement of cognitive dysfunction in AD, with effects being more pronounced with choline alphoscerate. Citicholine is a choline donor, and as CDP- choline, an endogenous precursor for phosphatidylcholine synthesis and has been shown to improve memory performance in elderly subjects with minimal negative effects, improve cognitive and mental performance in AD and vascular dementia. Some nutrients and herbs have also been shown to have cholinergic action: epigallocatchin-3-gallate (EGCG) and genistein exerting their known antioxidant effects via activation of nAChR signalling and subsequent cascades.

The cholinergic pathway can be further supported by the use of anticholinesterases which increase the levels of acetylcholine in neurosynapses. The acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme is found particularly in the brain, nerve cells, and erythrocytes, and is involved in hydrolyzing the acetylcholine ester. Altering AChE activity may thus help to restore the cholinergic balance by reducing ACh hydrolysis.

Pharmaceutical anticholinesterases increase both levels and actions of acetyl-choline found in the CNS and PNS and are most commonly used in treating chronic neurogenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s dementia, Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, characterised by destruction of ACh producing cells. Peripheral-acting cholinesterase inhibitors raise postsynaptic muscarinic Ach receptor activation eg pyridostigmine and are often used in conditions such as myasthenia gravis, Pyridostigmine (Mestinon) has also been trialled in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) with some success and as the symptomatic and exercise tolerance profile of PCVS overlaps significantly with ME/CFS, it is possible that this may be of therapeutic benefit also in managing ongoing symptoms of spikeopathy.

Some herbs hava also been demonstrated to have anti-AChE activity. Bacopa monniera, a traditional nootropic herb is one such herb, also up-regulating BDNF and M-1 receptor expression and restoring levels of antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation. Huperzia serrata is a traditional Chinese herb and the source of Huperzine A, a novel alkaloid which has proven to be a highly specific, reversible AChE inhibitor. Flavonoids have also been found to have strong biological activity and AChE inhibitory activity; Ginger and Cyperus rotunda have been demonstrated to have strong inhibitory action on AChE and Moringa oleifera leaves extract have been shown in rats to antidote venom of Naja nigricollis, (black spitting cobra) the first identified a-neurotoxin, 3-finger snake venom with which spike protein has been demonstrated to share sequence homology.

There are many studies of the activity of polyphenols as AChE inhibitors, which in addition to inhibiting AChE activity, also have an antioxidant effect, including scavenging free radical forms of oxygen and the ability to chelate transition metals, which reduces initiation of inflammation that can cause destruction of neuronal structures. In a study of 90 extracts from 30 medicinal plants on AChE activity, 23 active compounds were identified, including most abundantly used flavonoids and dihydroxycinnamic acids: the commonly known and used traditional herbs lavendar, oregano and thyme all tested positively with high AChE inhibition. Flavonoids, such as quercetin, kaempferol and, to a lesser extent, luteolin have also been reported as efficient AChE inhibitors. Some other traditional herbs such as Salvia L. species, Angelica officinalis L., Hypericum perforatum L., etc also have been demonstrated to have AChE activity. In a recent review, Shoaib et al have listed numerous other plants and their derivatives with AChE inhibitory activity. Apart from nicotine, there are thus many lifestyle, food based, herbal and supplemental means of modulating the ANS and thus exerting effects on the CAP which can be incorporated on a long-term basis. Ideally, interventions should be included as part of broader lifestyle and wellness protocols such as the ‘Revaya Wheel of Life’.11

SARS CoV-2, PACS and PACVS in common demonstrate the effects of spikeopathy with abnormal immune activation and involvement of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Noting the homology of a section of the spike protein ectodomain near the receptor binding domain to a- neurotoxoin and the neurotoxic rabies glycoprotein, it has been postulated that nicotine may beneficial as a cholinergic agonist. While it appears that the neurotoxic like region of the spike protein may alter a-7nAChR function allosterically, there is little evidence for any benefit of nicotine: indeed, on a cellular level it has been demonstrated to enhance the effects of the glycoprotein, is nonspecific to the a-7nAChR, and is well documented to induce desensitization of the ACh receptors, dependence and addiction. There are however numerous lifestyle, physical interventions, dietary and supplemental interventions which can enhance cholinergic function, by improving vagal tone, providing cholinergic agonism and reducing hydrolysis of acetylcholine. These interventions should be promoted as they are safe long term and have the added benefit of improving overall health and wellness.

This paper draws heavily on Dr Cosford’s previous paper.

Dr Cosford has no conflicts of interest to declare and no financial interest in any of the interventions mentioned.

©2025 Cosford. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.