Advances in

eISSN: 2377-4290

Case Report Volume 15 Issue 2

1Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Kasr Al-Ainy Hospitals, Cairo University, Egypt

2Professor of Ophthalmology, Kasr Al-Ainy Hospitals, Cairo University, Egypt

Correspondence: Randa Mohamed Abdel-Moneim El-Mofty, Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Kasr Al-Ainy Hospitals, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

Received: June 14, 2025 | Published: July 29, 2025

Citation: El-Mofty RMAM, Macky TA. Branch retinal artery occlusion with simultaneous branch retinal vein occlusion in healthy young patient. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2025;15(2):60-63. DOI: 10.15406/aovs.2025.15.00487

Simultaneous branch retinal vein and branch retinal artery occlusion can occur in healthy young patients without apparent cause, every attempt of treatment is made to save vision and proper assessment of the patient is mandatory.

Keywords: Branch retinal artery occlusion, branch retinal vein occlusion, anti-VEFG, retinal vascular occlusion.

The occlusion of the branch retinal artery can occur along with branch retinal vein; however, this is very rare, and particularly in individuals younger than the age of 30 years.1 Combined BRAO and BRVO are different from the clinical point of view from the entities of combined occlusion of central retinal vein and artery, and combined occlusion of the cilioretinal artery secondary to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).2,3 Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) when occurring should be regarded as significant as central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) as it carries the same clinic pathological importance; it is important to try to identify any underlying etiology.4

We have encountered a case of branch retinal vein occlusion coincident with branch retinal artery occlusion in a healthy young male.

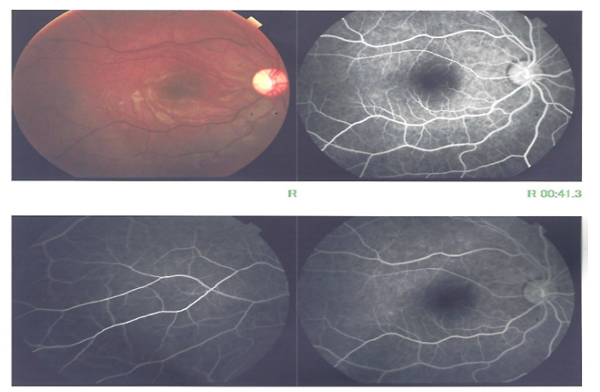

A male patient of 18 years of age came to the outpatient clinic of the Ophthalmology department of Cairo University, with a 3-day history of acute painless vision loss in the right eye along with visual field defect. He had a negative past medical history and was in good health apart from frequent attacks of headache most probably migraine. He was not taking any medication except for an “on the shelf” medication for common cold one day before the event. The patient was a heavy smoker and an alcohol user. On examination, the affected eye showed of counting fingers at 3 meters while the other eye, on the Snellen visual acuity chart, was 6/6. The right eye was quiet apart from relative afferent pupillary defect. The intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg. The right upper macula showed edema and hemorrhages with sectoral whitening corresponding to the retinal area supplied. The superotemporal retinal artery was attenuated. The retinal veins showed dilatation and tortuosity. Scattered flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages in the affected area. The optic disc was not swollen. No emboli could be seen, no signs of retinal vasculitis or fundal lesions at any other area (Figure. 1A). The left eye had no abnormalities.

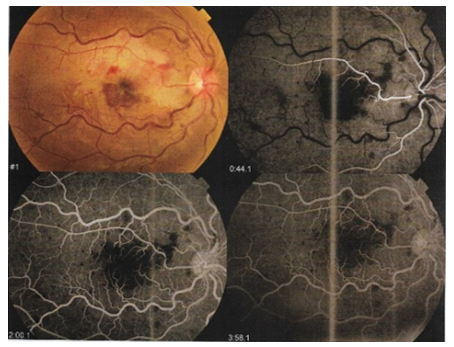

Figure 1 A Fundus photograhy of the right eye showing upper macular sectoral whitening, attenuated superotemporal retinal artery, dilated tortuous retinal veins and flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) was performed immediately at the Laser and Investigative Unit at Kasr Al-Ainy. It showed choroidal ischemia, delayed arm to retina circulation time (39 seconds), delayed A-V transit time with normal choroidal filling. The macular area showed areas of blocked fluorescence corresponding to hemorrhages & showing late leakage (diffuse macular edema) with enlargement of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ). The upper part of the posterior pole showed areas of blocked fluorescence corresponding to hemorrhages, the posterior pole and the peripheral retina showed extensive areas of capillary drop out (retinal ischemia) (Figure. 1 B).

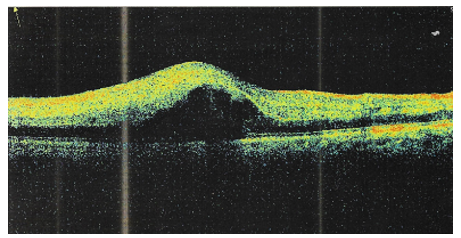

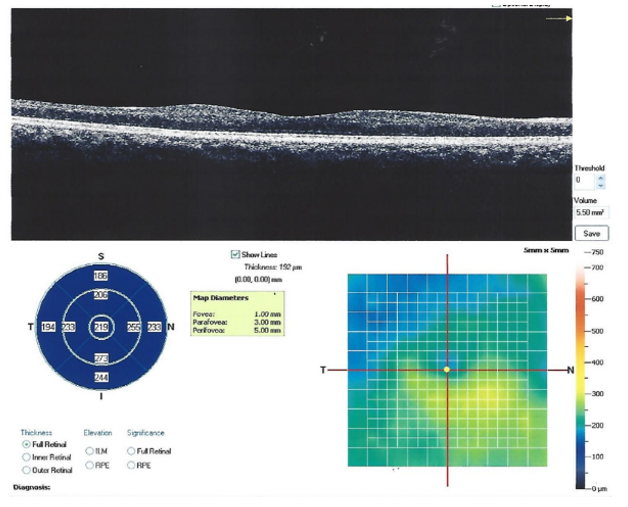

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was also performed, it showed altered foveal contour and depression, partial posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) around the fovea with no vitreomacular traction, diffuse subretinal hyporeflective fluid with cystic spaces (cystoid macular edema) and separating the neurosensory retina from the RPE-choriocapillaris complex (neurosensory macular detachment). Macular hemorrhage in the inner layers. Interrupted IS/OS junction (Figure 2).

Figure 2 OCT of the right eye showing diffuse subretinal hyporeflective fluid with cystic spaces separating the neurosensory retina from the RPE-choriocapillaris complex.

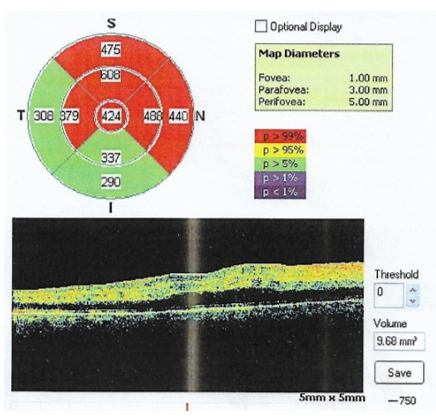

Retinal thickness map showed increased central foveal thickness (424µ) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 A. Retinal thickness map showed increased central foveal thickness (424µ). B. OCT image of the macula showing diffuse hyporeflective fluid separating the neurosensory retina and RPE choriocapillaris complex involving the fovea suggesting neurosensory macular detachment .

The patient was referred to an internist to check his general condition and the function of all major systems; the patient was normal, pulse and blood pressure were within normal range, and the patient gave no history suggestive of ischemia such as claudication or transient ischemic attack (TIA). The patient underwent multiple medical tests that included complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (C-RP) and coagulation profile in the form of prothrombin time (PT), prothrombin concentration (PC), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and international normalized ratio (INR). CBC results were as follows: Hemoglobin, 13.7 g/ dl; white cell count 7.3x 103/mm3; platelets 228 X 103/mm3. Carotid duplex was also done and was normal.

The patient, on the day of the event, received carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (acetazolamide) 500 mg I.V. and eye drops in the form of a combination of (carbonic anhydrase inhibitor and β-blocker “dorzolamide hydrochloride and timolol maleate”) twice per day. When the patient presented to us (3 days after the event), he was scheduled for a single intra-vitreal Anti-VEGF (bevacizumab, 1.25 mg) given 3 days later.

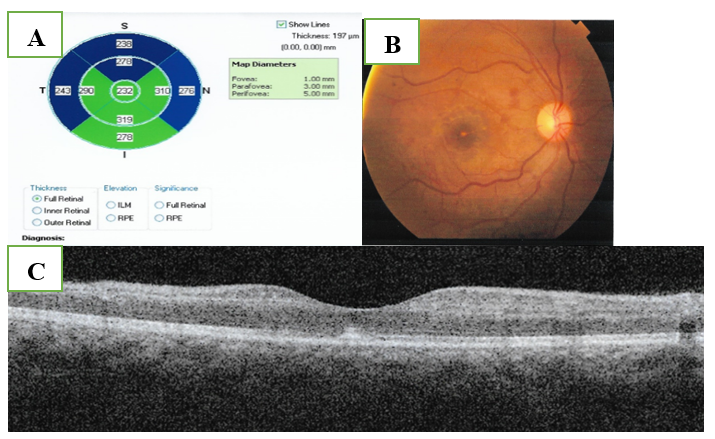

Two weeks later, visual acuity was regained to 6/60 by Snellen’s visual chart, retinal edema along with the retinal hemorrhages decreased significantly. Fundus photography and OCT-macula were performed (Figure.4).

Figure 4 A. Fundus photography of the right eye showing resolved hemorrhage and retinal edema.

C. OCT showing resolved macular edema and neurosensory detachment. Diffuse degenerative thinning of the peri-foveal region especially the superior para-foveal area.

One month following the initial presentation, the visual acuity in the right eye is 6/36 by Snellen’s visual chart, the fundus showed optic disc pallor of its superior half.

Five months following the initial presentation, on routine follow up after a period of drop out, the patient showed visual acuity of 6/24 by Snellen’s visual chart with lower visual field defect, the fundus showed disc pallor especially up and temporal, the macula appeared resolved but with abnormal reflex. FFA for the patient was done in which no abnormalities were detected (Figure. 5).

Figure 5 A. Fundus photography showing disc pallor especially up and temporal, the macula appeared resolved but with abnormal reflex.

B.FFA with no abnormalities detected.

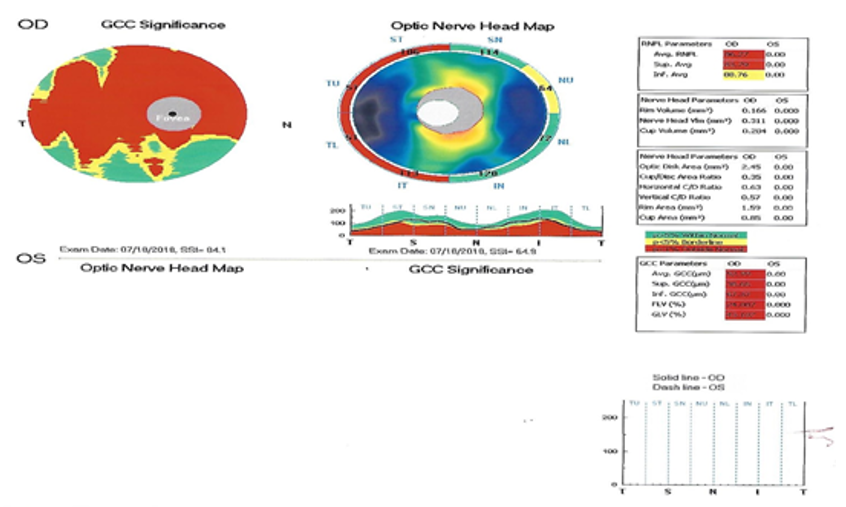

OCT of the macula was done and showed Hyper-reflective epiretinal membrane with no traction, decreased central foveal thickness (219µm) with diffuse thinning of the parafoveal and the perifoveal areas especially temporally (Figure. 6).

Figure 6 OCT showing hyper-reflective epiretinal membrane with no traction, decreased central foveal thickness (219µ) with diffuse thinning of the parafoveal and the perifoveal areas especially temporally.

Optic nerve head map was done, the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness showed thinning of high significance affecting the temporal quadrants and thinning of borderline significance of the upper nasal quadrant (Figure. 7).

Figure 7 Optic nerve head map showing thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer of high significance affecting the temporal quadrants and thinning of borderline significance of the upper nasal quadrant.

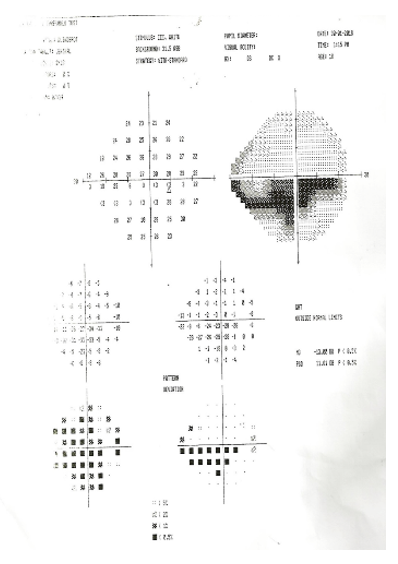

Humphrey Perimetry was done for documentation of the visual field defect and it showed marked reduction of generalized retinal sensitivity (MD = -13.00 DB), baring of the blind spot and lower nasal dense localized paracentral relative scotoma of high probability with encroachment on the central visual field in the lower hemi-field (Figure. 8).

Figure 8 Humphrey perimetry printout showing marked reduction of generalized retinal sensitivity (MD = -13.00 DB), lower nasal dense localized relative scotoma with encroachment on the central visual field in the lower hemi-field.

Eight months later, the patient’s visual acuity was stable at partial 6/24 by Snellen’s visual chart by peripheral field. The patient was asked to perform more recent OCT, but he did not. The patient had given his consent to share his clinical data.

Simultaneous combined retinal vein and artery occlusions are infrequent and have been reported in patients with Behçet’s disease systemic lupus erythematosus, hyperhomocysteinemia , and leukemia.5 Sengupta and Pan.,2017 described a case series of six patients with age range: 39-60, all of them had associated systemic comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperhomocysteinemia and dyslipidemia.6

Zuo et al.,7 reported a 30-year-old male case, with a history of atrial septal defect (ASD) who presented with unilateral simultaneous BRVO and BRAO. The patient had. They advised that heart disease should be ruled out in such cases, especially when affecting the same retinal quadrant.7 Bromeo et al.,2022 have reported a 47-year-old case of combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion as an uncommon complication following trabeculectomy.8 Ruiz and González-López.,9 reported the first case with unilateral simultaneous BRAO and CRVO in a 51-year-old patient after Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination.9 Systemic vascular thrombosis is a well-known complication of COVID-19 that have been attributed to the hypercoagulability induced by coronavirus infection.10 Also, retinal vascular occlusions have been reported after COVID-19 vaccines administration.11 The exact etiology of the presented case is unknown, however there are theories that can be postulated. The patient has special habits such as smoking & alcohol intake, which are increasing the risk of development of emboli resulting in retinal arterial occlusions.12 Also, due to cigarettes smoking, there is a chronic exposure to low levels of CO resulting in tissue hypoxia, mostly because of reduced blood oxygen carrying capacity and augmented blood-O2 affinity.13 In acute heavy alcohol consumption as well as in chronic high dose, there is higher risk of vasospasms or ischemic heart disease.14

The patient had a history of migraine attacks with also increases the risk of RAO, as Brown et al. reported in their study that almost one third of the patients with retinal artery occlusions in young adults had history of migraine.15

The patient also gave history of drug intake of a common cold medication containing Phenylephrine-DM-Acetaminophen, which has a vasoconstrictive effect on both cardiac and peripheral circulation, although it is rare.16 In the peripheral vasculature, vasoconstriction can occur due to stimulation of α-1 adrenergic receptors.17 Pseudoephedrine, as a sympathomimetic agent, can be involved in the initiation of coronary spasm and may cause myocardial infarction in some patients.18 It should be noted that the vasculature of the heart and the eye share many common features and are often exposed to the same intrinsic and environmental influences.

Another theory is “idiopathic” occlusion due to unknown event in which the previous postulations are only risk factors and not the direct cause. The recent drop in visual acuity appeared to be caused by atrophic changes in the fovea and optic nerve head (ONH), as long-term consequences of the initial BRAO. The initial improvement of the visual acuity could be explained by the improvement of the macular edema secondary to BRVO due to the anti-VEGF intra-vitreal injection. Systemic evaluation for cardiovascular risk factors is needed in cases of combined retinal vein and artery occlusion (CRVAO) which is considered as a rare emergency requiring early diagnosis and treatment.

The absence of an echocardiogram and inflammatory markers constitutes a limitation in our case. According to the internist, these tests were deemed unnecessary due to the lack of positive history and a comprehensive general examination. However, we recommend these tests, as complete testing is necessary to determine that "the exact etiology is unknown." 19–21

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2025 El-Mofty, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.